The compulsion to make lists too often seems to take the place of experiences in real life. We compile lists as a way to justify that we have been there, seen that, read this, and by putting it to paper our testimony should serve as an example for others. Does it mean list compilers are experts? Does it mean that everything on these lists is immediately rendered sacrosanct by association? From the absolutism of the Ten Commandments to online year-end claims of the “10 Best” movies, songs, and books, we gravitate to these lists because they are disposable and perfect time capsule artifacts. Some may be nourishing, others not, but they definitely know how to start (and sometimes definitively end) conversations.

How do we approach lists that are also reference texts? James Mustich‘s 1,000 Books to Read Before You Die: A Life-Changing List is as nourishing and addictive as it is slightly problematic. Certainly that latter part will only apply to those of us who approach such texts looking for a fight. The very title of this book might also be a little annoying. Is there a mirror list to read after we die? We examine every entry, analyze agendas, and scramble our own counterpoint to a volume so carefully curated. In his introduction to this 960-page book, Mustich notes that writing a book about 1,000 books in which each entry deserves commentary will serve different purposes for each reader:

“…inveterate readers read the way they eat-for pleasure as well as nourishment, indulgence… education… transcendence… Hot dogs one day, haute cuisine the next.”

Mustich notes that texts are never static, and that the organization will probably be peculiar for a reader unclear of where they might go and what they might want. His claim that the text is not meant to be comprehensive is more believable than his claim that it has no claim to being authoritative. That latter claim is unavoidable, especially for a text that claims familiarity (let alone intimacy) with these titles will change your life. The titles are primarily organized alphabetically by author. Roughly half the 1,000 titles are non-fiction; 948 are treated with individual entries; with the remaining 52 cited in “More to Explore” and “Booknotes” sections. The “Miscellany of Special Lists” section in the end features titles under such categories as “12 Books to Read Before You’re 12”, “From the 21st Century”, “Soul Food”, and “Read in a Sitting”.

The reader should be aware that this is an ambitious collection even if it’s approached with the intention to chew each section separately, carefully, enjoying the flavors as they make themselves known and eventually dissolve into your mind. The informed reader might already be familiar with such reference titles as Clifton Fadiman’s The Lifetime Reading Plan, and Mortimer J. Adler’s Great Books of the Western World, both of which suffer from their insistence on what is seen today as the Great Dead White Male masters syndrome. Harold Bloom’s The Western Canon also suffers under the weight of authoritarianism and pomposity. Mustich and his advisors and co-writers Margot Greenbaum Mustich, Thomas Meager, and Karen Templer, however, have compiled a work here that is relatively free of pomposity and authoritarianism.

Who is the audience for a reference book whose accomplishment (an impressively catholic collection of titles) sometimes comes at the risk of more carefully choosing titles that have stood the test of time, again? Any of the complaints a skeptical reader might have here have to be considered when examining those authors who are not represented at all. Joyce Carol Oates is not included except for a suggestion in the “Try” category after an entry on Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking. Both Oates and Didion deserve more time in this book. Likewise the remarkable canon of TC Boyle is not even referenced except in an addendum to an entry for John Irving. Richard Russo is added to the end of a John Casey entry. Where is Dr. Benjamin Spock’s Baby and Child Care? Where is Pete Guralnick’s remarkable two-volume biography of Elvis Presley? How about Robert Coles or Jonathan Kozol? Don Delillo gets only two minor references, and Ian McEwan only one. Kingsley Amis is here, but there’s no Martin Amis. Absent as well are Walter Mosley, Yukiko Mishima, Dalton Trumbo, and Richard Powers. Kurt Vonnegut, E.L. Doctorow, Henry Miller, Russell Banks, and Saul Bellow are only represented respectfully by one title. Paul Auster is not mentioned except for his work as a translator.

The absence of these titles and authors only becomes more frustrating when we see what could have been removed. Do such titles as Ender’s Game, The Hunger Games, Andromeda Strain, The Da Vinci Code, The Hunt for Red October, Master and Commander, and Presumed Innocent really deserve separate entries? There’s nothing inherently wrong with these titles. While they seem to serve as stand-ins for the genres (dystopic fiction, sci-fi, mystery) they only pale in comparison with many of the other titles. Mustich could definitely improve this text in future volumes by removing these titles and replace them with more than just single entries from authors already mentioned. It might result in a reference book that still leans towards the Western canon, or the white male author (dead or not), but at least it will lean towards more literate and quality work.

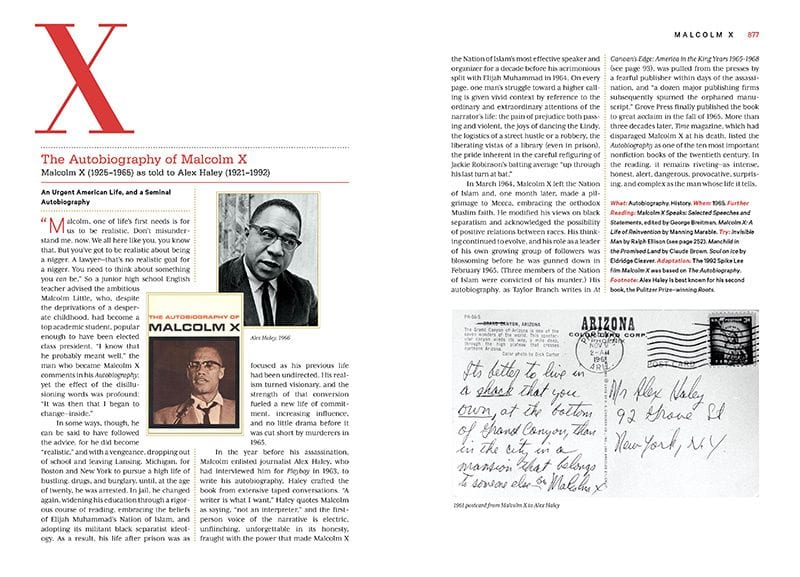

1,000 Books to Read Before You Die works best when we come upon treasures that are either still literally in our own collections or figuratively ingrained within our very spirit. James Agee and Walker Evans’ masterful study of the Great Depression, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, is justifiably on the list, waiting to truly change your life. L. Frank Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz is there with Roberto Bolano’s epic 2666. Taylor Branch’s masterful trilogy America in the King Years is there with John Dos Passos’s USA trilogy. Charles Dickens and William Shakespeare are generously represented, along with singular masterpieces from Frederick Exley (A Fan’s Notes) and Jeffrey Eugenides (The Virgin Suicides.) Allen Ginsberg’s Howl and other Poems is properly recognized, but even more satisfying is seeing Lucy Grealy’s remarkable and heartbreaking Autobiography of a Face on the list. Madeleine L’Engle’s A Wrinkle in Time and Norton Juster’s The Phantom Tollbooth take their place alongside Barack Obama’s Dreams from My Father and Art Spiegelman’s The Complete Maus.

It remains to be seen how the average reader will take to this book, but it shouldn’t bother Mustich, his collaborators, and this beautifully produced volume from Workman Publishing. It’s intentions seem sincere and clear rather than mandated and prescriptive. There are more welcome additions that could have held their own on this list: Crockett Johnson’s Harold and the Purple Crayon, Virginia Lee Burton’s Mike Mulligan and His Steam Shovel, or John D. Fitzgerald’s wonderfully evocative and beautifully illustrated (by Mercer Mayer) The Great Brain series. Granted, these are all children’s or young readers titles, but they are among the first that plant the seeds of possibilities in the minds and hearts of a lifetime reader.

No matter how we feel about 1,000 Books to Read Before You Die: A Life-Changing List, it deserves a prominent place on the shelf of any serious reader. Those of us who have spent our lives reading books, writing about books, collecting volumes sometimes at an alarming rate only to suffer anxiety once we realize we literally need more space to breathe will take this book to heart. If you have spent too much time apologizing for your reading, justifying your book purchase habits, and having to code switch in real life encounters when you suddenly remember that the person with whom you’re talking has no understanding of your literary references, take heed. Each entry is carefully and succinctly summarized, analyzed, and evaluated without making the reader feel bad for having never heard of the title (or not yet gotten to it.)

The classics (Plato, Shakespeare, Jane Austen, major religious texts) are equally balanced with the small treasures already mentioned in this review. Space limitations obviously prevent inclusion of quotes from the given texts, and these mini-essays that constitute discussion of each entry are less critiques than informative texts designed to motivate readers towards reading. In the end, that’s the highest ideal of any reference book, from Leonard Maltin’s movie guides through to any of the numerous high-minded literary reference guides all too familiar to those of us who have lived in the land of the Ivory Towers. Those of us who have journeyed through most of these titles will welcome becoming re-acquainted with them here. Others should be in for a wonderful time where each branch on the literary tree leads to an endless series of equally strong, important, heretofore hidden boughs.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)