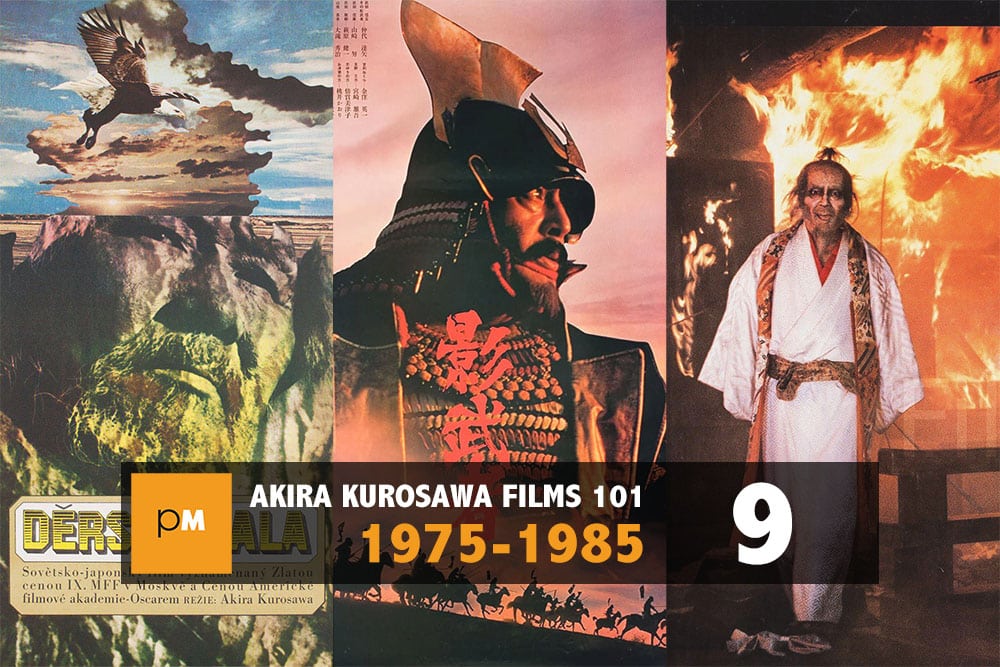

Dersu Uzala (1975)

A story of solitary survival and shared survival, nature erasure, and growing old, Dersu Uzala has an unusual and redemptive place in the Kurosawa canon. This first film after his 1971 suicide attempt was Kurosawa’s sole project abroad — a collaboration with Mosfilm, shot entirely in the USSR — as well as his only Foreign Language Oscar winner (Rashomon predated the Foreign Language category, but was awarded an Honorary Oscar in 1952). Yet the script revisits a book Kurosawa had first loved and begun adapting decades earlier: Dersu Uzala, Russian surveyor Vladimir K. Arseniev’s 1923 memoir of exploring the Ussuri River region (near Vladivostok) in Siberia. The text was itself animated by the author’s ink sketches: a flock of birds frills a paragraph, footprints in snow stipples a margin. Shot in 70mm, Kurosawa’s rendering, in turn, features some of the director’s most painterly vistas and immersive soundscapes.

Its 1910 when the film opens: in an area once sylvan, now razed for settlement, Captain Arseniev (Yuri Solomin) searches for a grave he can no longer find. “Dersu!” he murmurs sadly — tolling the tale back to 1902, when he and his soldiers first meet this stout, soft-footed hunter, an indigenous Goldi, who agrees to become their guide. Blunt yet pensive, Dersu Uzala (Maxim Munzuk) abridges grammar, talks to inanimate objects, has no notion of money, and doesn’t know his age — sure only of having “lived a long time,” outliving his wife and children. But his intuitions in the wilderness prove forensic and life-saving.

Trust and mutual esteem soon bond hunter and captain. Stranded near a frozen lake before a storm, scrambling to cut grass for shelter by nightfall, Arseniev nearly dies but for Dersu’s wits and stamina. The other Russians, too, grow to respect the Goldi’s animist ethos: “All is people. Fire, water, wind. Three mighty people.” At the trek’s end, Arseniev invites him home to the comforts of town, but Dersu cannot imagine leaving the forest. They part wistfully, full of goodwill.

During a 1907 expedition these two friends reunite — tumbling into an embrace, talking late into the night — and Dersu guides the men once more. Failing eyesight besets the now older hunter, however, as do fears that a tiger he killed will come back to claim his life. He moves into the Arsenievs’ home, only to atrophy blanket-swaddled before the fireplace: “I sit here like a duck. How can men sit in box?”

With Arseniev’s gift of a new rifle he returns to the forest. In the very next shot, news of his death arrives by telegram. It appears he was killed for his gun. Arseniev travels to identify the body, lingers watching as the gravediggers finish their work, and then marks the grave with Dersu’s walking stick.

The palette in this film recalls the richly saturated, ineffably Russian paintings of Ilya Repin: dark forests, ferruginous soil, snow at day that has the pallor of aluminum and ice at dusk the burnish of copper. Veins of red light enmesh a tiger prowling at night; campfires smoke up blue air.

Siberia here feels like an edgeless Ur-Asia where nationals and nomads alike carry on elementally, untouched by time or regime. A Chinese ancient roams lovelorn and lost in thought. An indigenous Udeghei family fries fish in silence. A folk sheriff and his followers patrol against bandits. The real Arseniev had many more encounters along the way — with Korean crab-men, Russian sectarians, Chinese pearl-divers, and ginseng-hunters, not to mention sea lions, bears, flying squirrel, wolverine, and other taiga-dwellers. Abiding by Dersu’s principle that “all is people,” Kurosawa minimizes those presences to invite in other forms of aliveness.

The swish of muddy ice floes softly colliding, the plash and purl of a brook, the crackle of kindling: aliveness here is always audible. Spoons and flasks hung to dry from icicled trees become wind chimes. In the Lake Khanka sequence, the hiss and rustle of grass-slashing thatch with Arseniev’s heaving for air as a spare incidental score (by veteran Soviet film composer Isaak Shvarts) glints and alarms. When Dersu sees train tracks for the first time, he puts not only a hand but an ear to the iron. Throughout this sound-suffused film, Kurosawa may well have had in mind his favorite line from Turgenev — on being able to tell the time of year simply by listening to leaves.

A moving portrait of friendship between two men, Dersu Uzala also imagines friendship between peoples. The Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905 is parenthetically implied when the film marks the expedition years of 1902 and 1907, and in the 1960s the Ussuri region became prime turf in Sino-Soviet border disputes. That Kurosawa had earlier relocated the story to Meiji-occupied Hokkaidô in his aborted project (as he did in The Idiot) suggests, too, that cultural survival was on his mind. As an elegiac vision of camaraderie among the diverse heritages populating eastern Eurasia, this film resonates powerfully with (Dodes’ka-Den co-producer) Masaki Kobayashi’s epic The Human Condition (1959-1961).

Filming Dersu Uzala took an expedition all its own. Kurosawa and his Japanese team of five, then four, spent 18 months in Moscow and Siberia, alongside a Soviet crew of seventy. The half-year in Siberia pitched them against a wayward boar and a depressed tiger, killing cold and hole-ridden film stock, endless reshootings that had Kurosawa in tears, feeling like Napoleon facing General Winter. In such conditions, the director might have found no better source of strength than Dersu himself: the bereft, aging hunter for whom a life intent on endurance, yet mindful of sharing the earth, endures as the most inviolable value.

A still-evolving appreciation for the director’s late style, and maybe the film’s double foreignness, and maybe its absence from the Criterion set, have kept Dersu Uzala among Kurosawa’s less screened, seen, and celebrated works. Unjustly so. It persists as one of his most humane yet more than humanist, affirming as well as mournful masterpieces. — Chinnie Ding

- Akira Kurosawa Films 101: 1963 – 1970

- Akira Kurosawa Films 101: 1960 – 1962

- Akira Kurosawa Films 101: 1955 – 1958

- Akira Kurosawa Films 101: ‘Seven Samurai’ (1954)

- Akira Kurosawa Films 101: 1950 – 1952

- Akira Kurosawa Films 101: 1949 – 1950

- Akira Kurosawa Films 101: 1946 – 1948

- Akira Kurosawa Films 101: 1943-1945

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)