A year ago, 19-year-old Cherlie Christophe lost her mother and her home in the earthquake in Haiti. Now she lives in a tent in a public square in Port-au-Prince. One night, she says, a man asked if he might come inside the tent, seeking respite from the rain. He raped her, and then, she remembers, “He kicked me, down there. My periods stopped, they haven’t come back.”

Cherlie appears in the new Frontline report, Battle for Haiti, premiering 11 January. She speaks quietly, wears a bright pink t-shirt, and the camera keeps a medium distance, the edges of the frame slightly blurred, creating a warped, disorienting effect, inviting you to imagine — however briefly and in accurately — how it might feel to have your life utterly upended. “The police said,” Cherlie sums up, “When you catch the gangster who raped you, call us.”

It’s impossible to represent the chaos in Haiti, because representation assumes and imposes at least a rudimentary order. For Cherlie and her neighbors, each day is chaos — unpredictable, frightening, and beyond words. Dan Reed’s Battle for Haiti respects that experience, and while it offers a version of Frontline‘s typically acute observations and wide-ranging interviews (with cops and gangsters, aid workers and parents), it also offers remarkable imagery, evoking the surreal life of Haitians now, a mix of daily horrors and bright sunshine, expansive poverty and tight quarters. It’s a beautifully constructed report on continuing trauma.

This report begins with shots of the National Penitentiary, close shots of barbed wire and damaged walls at sharp angles; in the long distance, inside the walls, buildings remain. As the soundtrack echoes with the sounds of inmates’ indistinct voices, narrator Will Lyman recounts that on 12 January 2010, the prison housed 4500 inmate: “Terrified inmates, packed 300 to a cell, ripped down the gates with their bare hands. Facing them were prison guards.” One of these guards adds, “We were 17 to 20 guards facing 4000 prisoners… It was dark, we couldn’t see a thing. All we could hear were screams, people crying out.”

The result was that most of the prisoners escaped, and gangsters — some notorious and many unknown — have taken up residence in the camps, where they can blend in, take power, and commit violence without fear of reprisal. For, as Lyman notes regarding Cherlie’s case, “The police have largely abandoned the people in the 1200 tent cities that sprang up after the earthquake in and around the capital.”

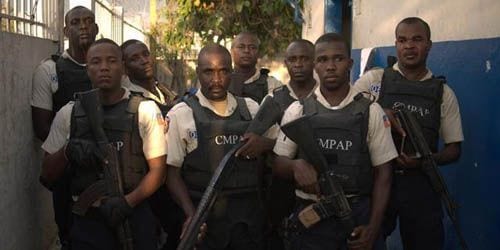

Frontline follows a couple of cops who are trying to reverse that abandonment, as they head out in vans to collect escaped prisoners. They rely on informants (whose motives are by definition suspect), they pick up pretty much anyone who is unfamiliar. Given the dire state of Haiti’s justice system, since long before the earthquake, some of those picked up will be released, and many others will head to prison, without a hearing, lost in “pretrial detention” whether or not they’ve committed an offense. The head of the U.N. mission, Edmond Mulet, points out the “appalling” conditions in prison. “They have 58cm per inmate and cant even sit down or lie down, they have to stand up like sardines in those cells.”

One police chief, Mario Andresol, laments the similarities between gangsters and politicians: “Honest people don’t go into politics in Haiti. That’s our great tragedy,” he says, “You have to belong to a closed circle of men who think only of themselves and who at times resort to killing.” His own job is increasingly impossible: “We weren’t set up to control these camps,” he says. “I haven’t enough men.” Lately, kidnap gangs have been wearing police uniforms and riding police motorbikes.

The camera follows Andresol’s officers as they search tents for weapons and load young men into trucks: the sunlight glints through the van windows, and prisoners weep. “I don’t blame you guys,” Jean Moise tells his captor, “You’re just doing your job.” An officer picks at him, hoping for a confession: “Stop that. Boys don’t cry.”

While some of the men’s names appear a on a list of prisoners who escaped during the earthquake, Jean Eddy’s story seems to check out: he was released before the quake, or at least he’s not listed as an escapee. When the cops cut off his handcuffs and prepare to let him out of the van, one insists he sing for them. Jean Eddy, caught between tears and joy, is undone. Though he does sing gospel, he says, “I’m a little stressed right now.” The cops clap and press him to sing anyway, and so he does: “Being a cop is a killer job / There’s nothing like it in the world / If you misbehave we take you down.” At last, he steps from the van, his face turned up to the light.

The hope was that relief workers and U.N. peacekeeping forces might have helped. But they’ve been sucked into what seems a vortex of frustration and stagnation in Haiti, a longstanding system based on fear and corruption. Without hope, without employment or education, people depend on “handouts.” As one tent city resident, Osée, observes, “It’s economic power that makes you an adult. In Haiti, the system is so corrupt you remain a child.” He holds a meeting with other residents, trying to track down how new tents are now being sold for profit. People are moving from slums to camps, imagining they’ll receive aid. The camps, Lyman narrates, “will now evolve into a new generation of slums.”

No matter how much aid money and effort Haiti receives, the lawlessness undermines all. Mulet insists that the international community is co-responsible for the “vicious circle we have been involved in for 30 years.” Nicole Orelus sells food in Cité Soleil, one of the worst slums in Port-au-Prince. “We shouldn’t constantly be given handouts,” she says. “That’s no way for a nation to be. We have to learn to work.” It’s a monstrous irony: Haiti might be defined by the work that needs to be done, but without infrastructure, a functioning government, or employment, no one can work.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)