It’s hard for me to know how the film will affect everyone, but my sense is that although it’s about this very heavy subject, the treatment of it mitigates that a little. I don’t think it’s depressing to see the film — there’s some hope and beauty to it.

A man holds his face in his hand. A car heads into a tunnel, your view framed through the windshield. A gas stove burner lights. A faucet drips… and drips. A man’s hand loads bullets into a revolver. Another man’s hand strops a straight razor, back and forth, back and forth.

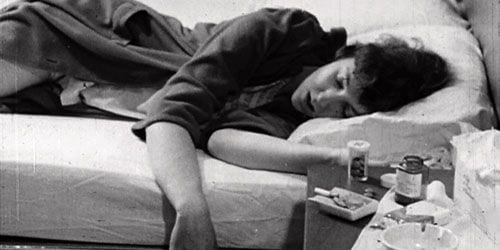

Seen separately, each of these images seems abstract, perhaps unmotivated. Taken together, assembled in The Darkness of Day, they tell a story, poetic and odd and poignant. Premiering 30 March on HBO2 and subtitled A Film About Suicide, Jay Rosenblatt’s short documentary is comprised of “found” 16mm images, footage that has been discarded. As such, it resonates with the subject matter, a meditation on sadness and also — on a sort of wonder at that sadness. “Strangely,” begins a journal entry dated December 18, 1983 and read over a scene of firemen retrieving the body of someone who’s jumped off a building, “I can recognize things as beautiful, but I do not feel moved by and of them or by anything else. I have ceased to care.”

Two points: One, the act of writing, of expressing such profound sadness, seems a paradox here, as it suggests caring even in the ceasing. Two, the film puts together any number of such paradoxes, juxtaposing images and voiceovers (a man and a woman read from journals, recall famous suicides like Ernest Hemingway and Primo Levy, pose unanswerable questions), not to parse them as much as to help you see them.

It is, of course, unspeakably sad to see the aftermath of a suicide, the body in the hands of officials, and also to think about how someone may have come to this point. A narrator notes the questions that typically follow a suicide: “We ask ourselves, ‘Why did it happen?’, ‘Why didn’t I see it coming?’, ‘If only I had done this or that.'” The very familiarity of these questions make them painful, as they suggest that something might have been “done,” that a chance for intervention has been missed. And yet, The Darkness of Day insists, motives for suicide aren’t always visible or comprehensible, even to the individual thinking about it. Putting pieces together after the fact, finding possible causes, can sometimes help survivors. While some suicides might be prevented — and so those at risk might be approached or “treated” — some are also essentially illegible.

A narrator quotes Albert Camus: “An act like this is prepared in the great silence of the heart, as is a great work of art. The man himself is ignorant of it. One evening, he pulls the trigger or jumps.” As you wonder about this, the relation of art to suicide, you see photographers gathered on the street below a potential jumper, ready to see what happens, to record it. A crowd waits. Flashbulbs pop. The utterly private becomes perversely sensational.

Most suicides, you know, are committed alone, but the location and means can reshape the act, can make it public, if still unknowable. This film recovers footage of the building of the Golden Gate Bridge, famous “suicide destination” (and the subject of Eric Steel’s 2006 documentary, The Bridge). Three months after the bridge opened, you hear, Harold Wobber, “a 49-year-old veteran of World War I, took a bus to the bridge, turned to a stranger, and said, ‘This is as far as I go.’ He then climbed over the railing and jumped.” You see the bridge and surrounding mist, you hear wind.

And as you can’t fathom how Wobber, the first of more than 2000 jumpers, made his choice, the film transitions from boats on the choppy water to what may lie beneath, dolphin. Found footage shows a dolphin caught up in a net and hauled on board a boat, as the narrator repeats the story told by Ric O’Barry in The Cove, concerning the suicide of Cathy, one of the dolphins he trained to play Flipper on the TV series. “It was deliberate,” the narrator recalls, “He said every breath is a conscious effort for a dolphin and she just stopped breathing.”

The film underscores the ambiguous and peculiar connections between these stories, as well as between the stories and vaguely corresponding images. The Darkness of Day invites you to put them together, to participate in processes of making sense. In fact, there are multiple process in Rosenblatt’s work, always bringing together pieces of pasts, reflecting on how filmmakers — amateur and professional — present ideas or express themselves. As Leo Goldsmith says of found footage — or “orphan film” — it reveals the “auratic value of celluloid itself,” in its imperfections, its uncertainties, its potentials. It relies on viewers for contexts, for meanings.

That’s not to say Rosenblatt’s assemblies are random, of course. The Darkness of Day, he says, “is not just about depression — suicide’s not just about depression. I didn’t want to have any moralistic judgments about suicide in the film, and I also wanted each story to highlight a different aspect of suicide.” These “aspects” are at once affecting and elusive. “Let it be recorded here,” asserts another journal entry, “that if I should meet an early and voluntary death, the reader of these pages will know the reason.” But such “knowing,” the film insists, can only ever be assembled as pieces.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)