Adapting Shakespeare for the movies would seem to be both easy and difficult. On the one hand, the stories are so sound, the language so sturdy that it seems all one needs is a suitable décor, a reasonable command of the camera, and actors with strong lungs and stronger memories. On the other hand, the plays are so internally vast, the scope of the words bearing so much more than their arrangement on the page, encompassing whole consciousnesses and psychologies, that one must concoct visuals sufficient enough to render and hold these worlds.

Akira Kurosawa was one filmmaker who was always up for and worthy of the Shakespeare challenge. His late-career film, Ran (1985), an epic re-telling of the Bard’s “old man” play King Lear, was a regally balanced combination of boldness and delicacy, and an eye-popping colorist’s dream. Throne of Blood (1957), newly released by Criterion on Blu-ray/DVD, is Kurosawa’s earlier adaptation of Shakespeare’s ghoulish power play Macbeth, and even at this relatively early stage in his career, the Japanese director had an assured adventurous approach to the material.

Shakespeare’s Macbeth is as solid as it gets, structurally, dramatically, even visually. The words summon images of such vivid power — the “weird sisters”, Lady Macbeth futilely scrubbing her bloodless hands, Macbeth’s imaginary dagger — that it is easy to forget that they are only words, a verbal conjuring stored up in our collective memory. Yet from the telling alone we see these things vividly.

Kurosawa comes up with indelible imagery to match. He’s absorbed the play’s intent, the murky physical and ethical world Shakespeare created, and transmuted it to the more personal milieu of Medieval Japan, a suitable historical shift as that era had the same fraught clannish tensions, and here, the same clank and clamor of Shakespeare’s Scottish armor.

Kurosawa’s boldest move is his interpretation of the play through the medium of traditional Japanese Noh Theater. The austere formalism of Noh, with its honed gestures and movements and its static yet expressive masks, might seem antipathetic to not only the high drama of Shakespeare’s raucous action and driving passions, but to the motile energy of cinema. In a documentary extra on the making of The Throne of Blood, Kurosawa notes the differences between Noh’s supposed stasis and cinema’s kineticism, but is also quick to point out that in the hands of a master, Noh is actually gripping and, in a sense, swift. Even to an audience acclimated to split-second editing, for whom the movements might seem slow and controlled, Noh can appear — again, in the hands of a master — just as thrusting or propulsive as any Western treatment.

Noh can also be quite chilling. Throne of Blood plays with frightening incongruity, its delicacy of movement expressing mortifyingly indelicate actions, as when Washizu (the Macbeth character) and wife Asaji (Lady Macbeth) deflate like punctured blow-up dolls as they resolve themselves to treason.

The Noh elements extend throughout the mise-en-scene, which is graphic as much as visual; the décor, the sets, the blocking of actors, all have a spare symmetry and asymmetry, with clean lines and pure visual patterns and rhythms. The rooms are walled with screens printed with fluid abstract designs, integrating the figures into the overall compositions like classical Japanese prints.

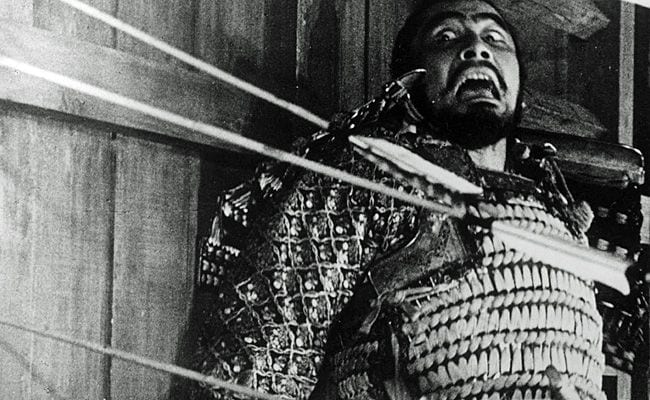

Washizu/Macbeth is played by Toshiro Mifune, Kurosawa’s frequent brute muse, an acting dynamo with the projective dimensions of Marlon Brando and the earthy panache of Clark Gable. Mifune’s Washizu, though strong and fierce as a warrior, is also always put-upon, confused, downright stressed-out. From the opening when he and Miki (the Banquo character) get lost in the forest and encounter the witch, through his wife’s machinations and up to his fate fulfilled, he seems increasingly lost and confounded. Though Kurosawa eschews the traditional masks of Noh, his actors retain mask-like expressions, so Mifune contorts and holds his face into vicious snarls and uncertain leers.

Isuzu Yamada, as Washizu’s wife Asaji, is one of the chilliest Lady Macbeth’s ever. By far the most Noh-inflected character in the film, she floats through scenes as if on hidden noiseless wheels, accompanied only by the whisper of her costume fabric rubbing against itself. Her face is the closest thing to a mask humanly possible, a soft yet stiff white melon with a mouth-slit tippling forth the most specious manipulations.

The energy Washizu sheds Asaji contains, discharging it only in small chilling detonations. Her motives are as mysterious as her method. Why does she pressure her husband so, twisting his strengths into weaknesses? A mere power conceit? Because where “ambition makes the man,” it apotheosizes the wife?

Mifune and Yamada form a powerful pair, her inner energy matching and even outsizing his. At one point, she goads from off-camera, as Mifune/Washizu prowls and stalks helplessly around his mat with clenching fists, contemplating a grisly moral equation: Murder + Treason = Power.

While Washizu crumbles visibly throughout the film, Asaji retains a porcelain stillness with nary a chink of conscience. This frigid façade makes its inevitable collapse all the more frightening; as she scrubs her bloodless hands, the eyebrows of her mask-face arch over her wide eyes like two tortured quotation marks. Kurosawa prefigures her inability to come clean with an earlier scene involving the unwashable wooden walls of a recent political suicide.

Washizu, like Macbeth, weakens with isolation. Successively bereft of friend, lord, wife and military might, he’s led to and misled by the witch or witches (the film seems to blend them) in the forest. Another of Kurosawa’s Noh-horror touches, the witch is a powdery white apparition perpetually web-weaving in Spider’s Web Forest (the film’s Dunsinane), whispering directly into the viewer’s/listener’s ear unnerving songs of man’s overreaching folly and the hell of life. After fulfilling the witch’s proclamations with inordinate irony, the film climaxes in a scene of near-comic absurdist excess: Washizu pierced and webbed under the unstoppable arrows of his own forces turning against him. The thousand arrows of outlandish fortune!

At times Throne of Blood feels like it could be performed identically on stage, yet despite its many theatrical aspects, Kurosawa remains extremely cinema-conscious. As quiet and still as the film often is, it also moves, with speedy montage and some high-energy rhythmic tracking shots through a mesh of branches, a kind of scrim behind which the figures race, increasing the action’s speed by lending an almost silent film-like kinetic flicker.

Cinema gives the play space and place. Washizu/Macbeth and Miki/Banquo lost in Spider’s Web Forest — a few deft mentions in the text — becomes a lengthy disorienting gallop through mountains of fog. Throughout the film, quick pans punctuate lengthy tracking shots of prolonged narrative tension, punching up the action.

This extends to Masaru Sato’s music. From the opening credits’ broody propulsive bamboo percussion and piercing flute that seems to meander over an open compositional field with funereal wailing and wavering, through the plaintive foghorn brass of the end, music matches movement, augments it, assists its carrying over. A steady wind blowing on the soundtrack creates a ghostly barrenness that’s flat-out scary.

With its notion of Macbeth’s guilt manifesting bodily, the play’s “Banquo’s ghost” scene has always frightened me. Kurosawa delivers with a figure dipped in white, glowing its own lurid light within the frame. Similarly, just as the ghost-banquet has always frightened, the movement of Dunsinane Forest near play’s end has always awed. Painted in the play with only a few words, here the effect is heightened with the visual of the swaying, heaving mass of trees in the mist, undulating, almost mechanically self-propelled. Kurosawa hints at this ploy with an ingenious touch: Hundreds of homeless birds fluttering into the castle.

This dual format edition offers a choice of translations by Japanese scholars Donald Ritchie and Linda Hoaglund. While the translations certainly vary, knowing the play and not knowing Japanese, I found myself ignoring the subtitles and just watching the images unfold — coherently. Testament to the clarity of both Shakespeare and Kurosawa.

Extras include audio commentary by Japanese film scholar Michael Jeck; a documentary on the film’s making; and a nice-size booklet with essays by film historian Stephen Prince and notes on the subtitles by the film’s two translators, Hoaglund and Ritchie.