Americans, and maybe everyone else too, love happy endings. Especially when they’re attached to messy beginnings and middles.

Conventional wisdom holds that all was right with major league baseball after Jackie Robinson desegregated it for good with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947. His very presence shattered the “gentlemen’s agreement” that kept the big leagues lily-white for generations, and his electrifying performance shattered any notion that blacks couldn’t excel on that level. Midway through that season, the Cleveland Indians signed a black player, outfielder Larry Doby, and other teams would follow in the next few seasons.

Since most accounts of Robinson’s story imply that the battles had been basically won by the end of his historic rookie season, it makes sense to look at how the desegregation of the major leagues actually played out. That’s the book promised by the lengthy subtitle of 1954: The Year Willie Mays and the First Generation of Black Superstars Changed Major League Baseball Forever. But the book Bill Madden wrote is much less racially charged, telling instead the story of an interesting baseball season. By the end of it, race is almost a footnote.

At the dawn of the 1954 season, five of the 16 big league teams had yet to add a black player to their rosters. One of them was the New York Yankees, which became the team under the most fire to do something about that (they would, a year later, with Elston Howard). The raw numbers weren’t much better, Madden reports: 27 blacks out of 448 big leaguers, just under six percent, on Opening Day rosters.

Many of them wouldn’t amount to much, but a few of them did. In 1954 we meet three of them: the Milwaukee Braves’ Henry Aaron, the Chicago Cubs’ Ernie Banks, and the New York Giants’ Willie Mays. Mays joined the Giants in 1951, but spent the next two seasons fulfilling military duties, while Aaron and Banks were brand new to the big leagues.

But instead of focusing on the players and their experiences (Where did they stay on road trips? Did their teammates accept them? What kinds of hostilities did they face? How did all this affect them as people?), Madden spends more time looking at their on-the-field contributions. In fact, he spends more time looking at the teams in general than considering their racial makeup, or the impact of integration on their fortunes.

And thus does 1954 settle into the leisurely rhythm of a typical baseball season. Madden focuses on the five teams chasing pennants that year: the Dodgers, Giants and Braves in the National League, and the Yankees and Indians in the American League. It’s a fun tale for diehard baseball history fans to read, as Madden captures the ins-and-outs of a highly competitive season. But it’s really not much more than a season’s nuts-and-bolts chronicle, without anything specifically compelling enough to indicate why this particular one matters more than others, especially when it comes to the difference-making presence of black stars on the winning teams.

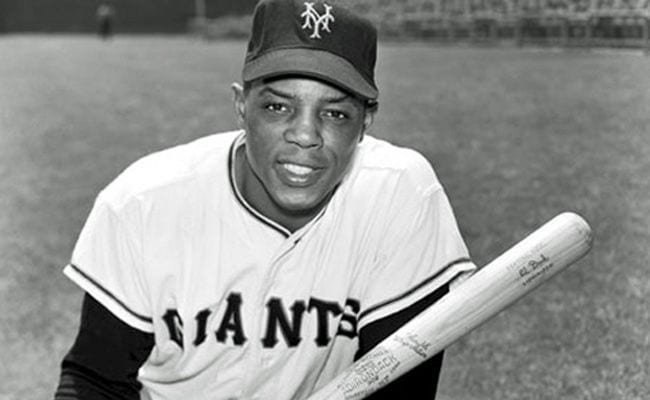

The Giants and the Indians reached the World Series, with Mays’ legendary catch becoming the defining image (and this book’s cover photo) of New York’s four-game sweep. If Madden is saying that by 1954, black excellence in baseball was no longer shocking, that’s one thing to note – but he doesn’t really note it.

He talks about the superstars on the contenders to some degree of detail (but you’ll want to refer to their biographies and autobiographies for their stories in depth), but not at all about what the subtitle implies. He does not consider the first wave of post-Robinson stars as a group, or what was germane to their experiences coming along once the barriers had been broken (taking this approach, he might have included the other black stars who came of age in the mid-‘50s, including Howard, Frank Robinson and dark-skinned Puerto Rican Roberto Clemente).

That’s one of history’s typical blind spots. The pioneers get all the glory, but those who immediately followed had an only slightly different road to travel, and often encountered barriers of their own along the way, but got little of posterity’s credit for it. The post-Robinson stars did not have to put up with anywhere near as much pressure as Robinson, but that doesn’t mean all was hunky-dory with baseball by then.

In fact, their emergence in 1954 didn’t change everything forever. It would be another five seasons before each big league team had desegregated its roster, when the Boston Red Sox added Pumpsie Green in 1959. Many spring training accommodations in Florida remained notoriously whites-only into the ‘60s, propelled into change more by local civil rights activists than by baseball itself. The major leagues wouldn’t see a black umpire until 1966, a black manager until 1975, and a black general manger until 1977.

Perhaps the book’s ballgame-centric narrative is to be understood: Madden’s a longtime sportswriter, not a sociologist or race historian. While he makes entertaining hay from the various machinations of the 1954 season, 1954 stands as a missed opportunity to tell a larger, more instructive story.

And a timely one too: after peaking in the early ‘70s, the percentage of African-Americans on Major League Baseball rosters is back down in the single digits. It’s been plummeting for years, for numerous reasons, and the efforts to reinvigorate black interest and participation in baseball are going to take a while, at best, to bear significant fruit. That stands in stark contrast to the bright future the emergence of all that remarkable black talent 60 years ago represented.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)