Excerpted from The Streets of San Francisco: Policing and the Creation of a Cosmopolitan Liberal Politics, 1950-1972by Christopher Lowen Agee (footnotes omitted). Published by the University of Chicago Press. © 2014 University of Chicago Press. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reprinted, reproduced, posted on another website or distributed by any means without the written permission of the publisher.

“I Will Never Degrade the Spirit of Unity”: Managerial Growth Politics and Police Professionalism

“I am going to warn you I am not accustomed to mincing words,” Mayor George Christopher thundered. Standing on the stage of the Commerce High School auditorium, San Francisco’s chief executive looked down upon hundreds of seated San Francisco police officers. Five days earlier, on January 8, 1954, Christopher had taken the oath of office on the heels of yet another SFPD scandal. In this latest embarrassment, federal Treasury officials had raided a bar offering open gambling just one block from the Hall of Justice. Christopher entered City Hall aiming to assert the authority of his office with a department-wide assembly. “I do not intend to have anybody tell me or the [Police] Commission that something has been under their noses and they don’t know anything about it,” he lectured. “Very frankly, if something is going on under your nose or under ours it means we are either blind or incompetent. And it means we are not fit to hold our jobs.”

With Christopher’s election, San Francisco joined a growing wave of cities turning to managerial growth mayors committed to clean-government reforms and downtown redevelopment. These mayors—including New York City’s Robert Wagner, St. Louis’s Raymond Tucker, Philadelphia’s Joseph Clark, and Boston’s John Hynes—presumed that downtown growth served the interest of all citizens. Those citizens, Mayor Christopher believed, maintained a host of preexisting shared values. He accepted nominal class and religious pluralism in civic debate, but asserted that the primary purpose of government was to never “degrade the spirit of unity.” The mayor believed that poor management produced factional rifts, and he proposed to avoid that pitfall by consolidating power in the hands of administrative experts from the business community. Christopher’s new Police Commission, for instance, consisted of a corporate lawyer and two former presidents of the city’s Chamber of Commerce. These new officials, he promised, would institute a system in which police officers were “promoted on merit, not by a mayor calling up someone and using his influence.” Christopher vowed that he himself would “administer the big business of San Francisco… on a sound, constructive, business-like basis.”

Christopher’s technocratic pledges thrilled the reporters crammed along the wings of the Commerce High School auditorium. The following morning, the San Francisco Chronicle’s front-page, top-of-the-fold coverage heralded Christopher’s fight against “inefficiency and corruption” as a generational sea change. When the assembly ended and the mayor and his police commissioners “invited” officers to shake their hands, the Chronicle reported, “younger officers in the department… went out of their way to stand in line and meet the officials.”

In truth, many of the young officers seethed. Thomas Cahill, who subsequently served as Mayor Christopher’s police chief, recalled that officers who considered themselves honest felt that Christopher “was casting reflections on them.” Sol Weiner, a three-wheeled-motorcycle officer, later characterized the speech as “rotten,” and Patrolman Elliot Blackstone remembered:

So Christopher got up, and he accused us all of being a bunch of thieves and crooks and everything else. But he said, “You know I’d be glad to work with you.” …And he made us all so mad. Then after he got done talking, we were all invited to come up on stage to shake hands with him. Well, I and two or three hundred of us at least turned around and walked out of there. We wanted nothing to do with this guy.

It likely never occurred to either Christopher or the journalists to survey the rank and file for their perspectives. The mayor and his supporters all trusted that the city’s common interests could be met through administrative, top-down reforms. Indeed, Christopher and his backers assumed that more than any other clean-government changes, police reform would convince the electorate of the efficacy and righteousness of managerial growth politics.

The Downtown Leadership and Police Professionalism

Mayor Christopher’s efforts at police reform during the mid-1950s represented the culmination of a decades-old battle between San Francisco’s downtown business leaders and the city’s traditional machine politicians. Similar downtown-versus-machine struggles had been roiling in American cities since the turn of the century, as large-scale business interests sought greater influence in urban affairs and machine politicians struggled to retain their political and financial independence from downtown elites. In cities like San Francisco, machine officials employed their licensing powers to collect favors and graft from small-business owners, and they used their appointment powers—over institutions including schools, fire departments, and public works departments—to earn the votes of working-class residents.

Through the first half of the twentieth century, downtown representatives attempted to bring their local governments to heel with clean-government reforms. In 1932 a group of San Francisco entrepreneurs, financial officers, and corporate executives—serving such economic behemoths as Bank of America, Standard Oil of California, Pacific Gas and Electric, and the Bechtel Corporation—scored a major victory in their city when they shepherded through a new city charter ending mayoral appointments to the public works department and transferring licensing authority out of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors and into the hands of various appointees. (San Francisco’s city and county lines are identical, so the board functions as a city council.) Because the 1932 charter retained the city’s at-large election format, candidates for supervisor now saw little choice but to turn to downtown elites for help in funding their expensive citywide campaigns. For the next forty years, the Board of Supervisors rarely wavered as a representative of the downtown leadership’s agenda.

During the late 1940s, new potential crises and windfalls motivated San Francisco corporate elites to press for further influence in local politics. San Francisco’s big-business leadership emerged from World War II alarmed that a downturn in local military spending and a concomitant rise in suburban and Sun Belt manufacturing threatened to drain San Francisco of its economic vitality. Through groups like the Chamber of Commerce, San Francisco’s corporate representatives responded to this threat with a regional plan that called for City Hall to remake San Francisco into a financial and administrative center—what one scholar termed the “brains and heart”—for a Bay Area–wide manufacturing economy.

The federal Housing Act of 1949 opened the possibility for just this sort of transformation. Under the new law, the federal government offered to cover two-thirds of the costs associated with purchasing areas pegged for redevelopment. Moreover, it permitted cities to sell or lease the lands to private developers at below-market values. In order to tap the Housing Act subsidies, the city government simply had to prove that an area under consideration for redevelopment was blighted and that the government had plans to renew the land with projects serving the civic interest.

The managerial growth advocates’ desire for new federal redevelopment dollars steered them into a final showdown with San Francisco’s traditional machine politicians. In 1947 San Franciscans elected Elmer Robinson, a former member of the judiciary and a committed practitioner of machine politics. When Congress passed the Housing Act two years later, downtown officials implored Robinson to install a competent director for the new San Francisco Redevelopment Agency (SFRA). Instead, Robinson tapped a political hatchet man who filled the SFRA’s staff positions with other political cronies. Robinson’s SFRA planners possessed neither the motivation nor the competence required to craft and submit redevelopment studies and plans. The various downtown redevelopment schemes thus floundered in what one scholar described as a web of “obstructionism and venality.”

Managerial growth proponents recognized that although charter reform had created an obedient Board of Supervisors, one final unreformed institution—the San Francisco Police Department—allowed the mayor to maintain his independence. Police departments like the SFPD had been sustaining machine politics since their creation in the mid-19th century. Machine politicians doled out important positions in their police departments with the expectation that beholden officers would get out the vote and collect payoffs for the machine’s campaign war chest. A 1937 inquiry into SFPD corruption—dubbed the Atherton investigation—found that San Francisco’s police served as “an organized and powerful electioneering force” that would solicit votes and “aid materially in raising campaign funds.” Indeed, the probe unearthed a vast network of payoffs linking officers of all ranks to the city’s gambling, prostitution, and bail bond industries. The Atherton investigation estimated that the SFPD collected on average over one million dollars per year.

Managerial growth advocates confronted this corruption with the concept of police professionalism. A product of the Progressive era, police professionalism followed the principles that reformers had already used to restructure other institutions underpinning the machine, such as schools. Professionalism advocates proposed to funnel police authority upward into the hands of an expert, nonpartisan police chief. This honest police leader, reformers assumed, would then use his autonomy to select and train officers dedicated to serving citywide interests through a vigorous campaign against crime. Police professionalizers were primarily concerned with the venal links between city officials and police department commanders, and they thus rarely offered specifics on what a professionalized police chief would do other than reject payoffs. Police professionalism, the legal scholar David Sklansky explains, was more of a “governing mindset” than a policy prescription.

Following the Atherton scandal, San Francisco’s Chamber of Commerce successfully lobbied for two charter amendments aimed at transferring power from district station captains to the chief of police. First, San Francisco increased the chief ’s oversight over district captains by joining a wave of cities (eventually including Cleveland, Pittsburgh, Rochester, Cincinnati, and New Orleans) consolidating police districts, reducing San Francisco’s fourteen district stations to nine. Second, it followed the lead of other municipalities by transferring responsibility for so-called vice crimes (a formal SFPD category that included gambling, narcotics, and sex offenses) out of the district stations and into a new Bureau of Special Services. The twelve officers of Special Services operated as part of the Inspectors Bureau but answered directly to the chief of police.

The Atherton reforms proved fleeting. The attempt to concentrate responsibility within the SFPD via the charter amendments meant little if the police chief did not then use his consolidated authority to crack down on payola. One observer noted that the centralization of authority over vice policing served simply to “centralize collections.” Reformers understood that corruption persisted with the consent of the mayor: the 1932 city charter had granted the three-member, civilian Police Commission authority over SFPD policies, appointments, and disciplinary decisions, but the commissioners served at the mayor’s will and thus attended to his interests reliably.

When Mayor Robinson took office in 1948, his Police Commission set out to create an SFPD arrangement conducive to the flow of favors and graft. The new administration appointed Michael Mitchell police chief, then immediately treated the SFPD leader as a straw boss. Robinson recognized that he could collect far more favors by bypassing Mitchell and personally doling out positions and authority along the two main branches of power extending from under Chief Mitchell. First and foremost, the police commissioners distributed prized positions within the Inspectors Bureau. The SFPD’s plainclothes inspectors enjoyed status and authority over uniformed patrol officers, and once inspectors were appointed, their positions were protected by their bureau’s tenure rules and Byzantine disciplinary procedures. As a result, the less motivated inspectors could spend their workdays thumbing through paperwork and keeping what one reporter charitably labeled “bankers’ hours.” Police commissioners racked up a multitude of favors for Robinson by transferring well-connected police officers to the bureau. Commenting on the active hand Robinson’s commissioners played in inspector appointments, the chief of inspectors explained, “I work on the theory that if the Police Commission will give me even one man I’ve picked out myself for every two men who are assigned to me, I’ll get along fairly well.”

Robinson’s Police Commission cultivated a second line of influence through key appointments within the district stations. Police commanders usually desired positions atop the Northern, Central, Southern, and Mission Stations because these stations covered neighborhoods (such as the waterfront, the Tenderloin, the Fillmore, and North Beach) with high-profile crimes and high-reward payola. Police commissioners usually limited themselves to command-rank appointments and then allowed police captains to run their districts as their own personal fiefdoms. On occasion, however, commissioners meddled with patrol posts along payola-rich beats. One of the Robinson Police Commission’s first acts was to replace a long-tenured patrolman assigned to the Broadway Street nightlife scene. Noting that Robinson’s Police Commission was “usurp[ing]” Mitchell’s “function as Chief ” “down to the placement and transfer of ordinary patrolmen,” the San Francisco Chronicle pondered, “What’s behind all this manipulation in the Police Department?”

By abetting police payola practices, Robinson’s machine ran afoul of state and federal police agencies warring against organized crime. Outside law enforcement officials repeatedly targeted San Francisco gambling houses that they feared might become footholds for East Coast gangsters. To the consternation of state and federal officials, SFPD officers on the take withheld assistance from and actively interfered with external investigations. Following one bookmaking sting by state agents, a local newspaper jeered, “The San Francisco Police Department was not informed of plans for the raid. Why? Apparently because the raiders wanted to succeed by surprise.” Mayor Robinson shrugged off these scandals and worked to roll back the meager post–Atherton investigation reforms. The mayor’s Police Commission sidelined the Bureau of Special Services by slashing the positions of all but three inspectors and returning vice policing back to the district stations.

Chinatown Entrepreneurs and Police Professionalism

During the early postwar period, business leaders did not press their professionalization campaign any further than was necessary for cutting off payola to City Hall and consolidating their power over the SFRA. San Francisco’s managerial growth proponents railed against the corrupt connections Robinson’s administration maintained with the SFPD leadership, but the police reformers rarely explained how an independent, professional police chief would set policies serving the citizenry’s shared values. This imprecision carried political benefits for professionalism advocates. By allowing various groups of San Franciscans to independently imagine how professionalized police reforms might serve their needs, the downtown reformers gathered a wide range of constituencies under their clean-government banner.

In Chinatown a new generation of Chinese-American businessmen joined the police professionalism movement in a broader campaign for full citizenship rights. Chinatown’s young entrepreneurs hoped that once managerial growth advocates achieved power, they would use professionalism’s emphasis on consolidated, color-blind police authority to grant Chinese Americans honest and equal law enforcement.

During the machine-politics era, the SFPD’s approach to Chinatown diverged further from the principles of police professionalism than its policies in any other area of the city. The department had created the Chinatown detail sometime around 1878 in response to neighborhood tong wars, but large-scale Chinatown gang violence had long since abated. Still, after World War II, the fifteen-member detail remained the SFPD’s only police presence in the neighborhood. An archetype for the core principles and practices of machine-era policing, the Chinatown detail was race conscious, free from day-to-day over-sight, disconnected from the residents it policed, and an integral component of the machine’s payola networks.

The Chinatown detail operated without any formal physical or functional connections to the regular police. Although the neighborhood was mere blocks from the SFPD’s Central Station, the Chinatown detail did not operate out of this district station. Instead, the detail was based in a small, secret Chinatown hideout. The office had a private phone line, but the desk was rarely staffed, so the detail maintained little daily contact with the Hall of Justice. At the same time, official SFPD policy forbade Bureau of Special Services inspectors or Central Station patrol officers from stepping foot into the neighborhood. Chinatown was thus the only residential neighborhood in the entire city not supervised by a district station and the Hall of Justice’s Inspectors Bureau.

The detail’s operational autonomy reflected the SFPD leadership’s bigoted attitudes toward Chinese Americans. The high brass articulated that prejudice when explaining why they allowed the Chinatown detail to forgo standard blue uniforms for stylish suits that made the officers look like “movie detectives.” One official suggested that Chinatown residents were too backward to associate blue uniforms with anything other than the “tyrannical officials of the courts of China.” Another SFPD leader stressed neighborhood insularity and criminality, warning, “In Chinatown the uniform tips your hand. That star shines up very nicely. They can see you coming blocks away… In many cases, such as gambling houses, a lookout or ‘look-see’ is posted outside. Police wearing a uniform would have a hard time gaining evidence.”

SFPD leaders further evinced their dim views toward Chinatown residents by discouraging dialogue between the Chinatown detail and Chinese Americans. During the 1940s and early 1950s, the police force did not require members of the Chinatown detail to possess any facility in Chinese languages and did not include any Chinese-American officers. (The SFPD as a whole did not employ a Chinese-American patrolman until 1964.) Moreover, the department made it impossible for neighborhood residents to contact officers by phone. In the days before two-way radios, San Franciscans living outside of Chinatown called a central communications hub, which then contacted the appropriate district station to arrange an officer response. Chinatown residents could not reach police in this manner because their detail was not attached to a station. The SFPD expected Chinatown residents to stand and wait for the detail to pass by the intersection of Washington and Grant streets or to leave a message at Red’s Bar at the corner of Jackson Street and Beckett Alley. These old-world arrangements enhanced the squad’s cachet with the nation’s true crime magazines, but the Chinese Chamber of Commerce complained that merchants often could not locate police when robberies occurred.

Although machine politicians gave negligible consideration to crime fighting in Chinatown, they did value the neighborhood as a well of graft. Postwar observers estimated that under the Chinatown detail’s watch, the neighborhood gambling industry generated six to seven million dollars in proceeds a year. Wide-eyed machine officials looking to tap into these proceeds jostled with one another for influence over Chinatown detail appointments.

It took Mayor Elmer Robinson nearly his entire first term to gain full control over the Chinatown detail. Shortly before he took office in 1948, the previous administration’s Police Commission tried to curtail the incoming mayor’s access to payola by abolishing the detail. Robinson had no trouble reactivating the squad, but he then found himself wrestling with his police chief, Michael Mitchell. Police details comprised short-term appointments set by the officers’ immediate supervisor, not the mayor’s Police Commission. The Chinatown detail officially reported to the police chief, and thus as soon as Mitchell became chief, he assigned a Chinatown detail leader loyal to himself. Indignant, Robinson attempted to replace Mitchell’s pick with his own police ally, but the chief went to the press and exposed Robinson’s meddling. Noting that authority over Chinatown appointments had “always been a sore spot,” Mitchell charged that Chinatown residents were “in league with the mayor” to “relax” Mitchell’s supposed demand that the neighborhood “stay closed.”

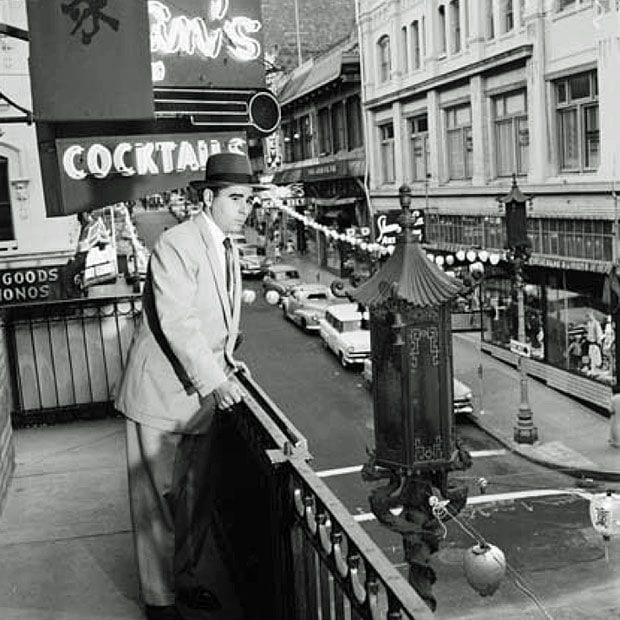

Officer Leo Osuna, a member of the Chinatown squad, overlooks a street in Chinatown. Chinatown squad members wore well-tailored suits rather than the SFPD’s standard blue uniforms. This sartorial choice allowed squad members to strike photogenic poses, but Chinese-American business leaders complained that the suits made it harder for neighborhood residents and visiting tourists to find and communicate with police. August 18, 1955. (Reprinted with permission, Bancroft Library, BANC PIC 2006.029: 138946.0208.)

Ultimately, Mitchell and Robinson established a truce in which detail officers under Mitchell and members of the Bureau of Special Services answering to Robinson’s Police Commission allegedly both exacted concessions from Chinatown gamblers. When Chief Mitchell retired at the end of 1950, Mayor Robinson streamlined the lines of loyalty. His new police chief took power announcing only a single transfer: a Robinson-approved officer at the head of the Chinatown detail.

Since the opening decades of the twentieth century, Chinatown’s entrepreneurs had hoped to earn more equal government services in housing, law enforcement, and host of other areas by reforming their neighborhood’s reputation. San Francisco’s traditional leadership conceived of family men as ideal citizens, but, as Nayan Shah has shown, these same city officials regarded Chinatown as “an immoral and disease-infested slum” occupied by working-class bachelors and female prostitutes. Through the first half of the century, Shah illustrates, Chinatown business owners attempted to overcome this impediment to integration by remaking their neighborhood’s image as a “family society of independent family households.”

Following World War II, Chinatown entrepreneurs found that their public relations efforts were being stymied by mainstream press reports on Chinatown gambling. These articles referred to illegal gaming as both an active Chinatown tradition and a threat (via roving lottery ticket sellers) to the rest of the city. When H. L. Wong, president of the Chinese Chamber of Commerce, later explained his motivation for developing the family-oriented Chinese New Year Festival, he emphasized his desire to rid the neighborhood of its gambling reputation. “I always saw the newspaper headlines ‘Chinatown Gambling Raid’ …in the pre–Chinese New Year Festival days,” Wong recalled. “I always grumbled, ‘What’s the matter with them? There are so many good things about Chinese and our Chinatown. Why do they play up this gambling?’ ”

These business leaders recognized that wiping away Chinatown’s gambling reputation and securing a family-oriented image for their neighborhood was not simply a project of reforming Chinatown residents and culture. The mission also required that Chinese Americans help clean up the white government in City Hall. Chinese-American spokespersons who wished to decouple Chinatown and gambling in the mainstream’s perception understood that “Chinatown Gambling Raid” headlines persisted because the SFPD refused to professionalize its policing of the neighborhood.

This public relations problem was worsening during the late 1940s as a new generation of local politicians curried downtown support with campaigns against police payola. Repeatedly, these reform efforts against police venality implicated Chinatown. In 1950, for instance, San Francisco district attorney Thomas Lynch took on the machine by recording testimony accusing Chinatown detail officers and Mayor Robinson’s Chinatown campaign organizer of receiving monthly extortion payments amounting to $35,000 from Chinatown gambling operations. That same year Sacramento legislators pursuing a similar clean-government agenda accused members of the Bureau of Special Services—which operated under the influence of the Police Commission and thus the mayor—of collecting Chinatown payoffs as well. One informant for this state inquiry claimed that Inspector George “Paddy” Wafer spent so much time inside a Chinatown gambling house that other customers mistook the detective for the establishment’s owner.

Chinatown’s business elites groused over the negative press, and they saw in police professionalism an opportunity to establish themselves as partners with managerial growth proponents. Young entrepreneurs and professionals in the neighborhood fumed over the fact that “of all the many racial groups in San Francisco the Chinese alone require a special police squad.” However, neighborhood spokespersons did not want to ruffle the feathers of those city officials empowered to abolish the detail with charges of race-conscious discrimination.

Spokespersons found a color-blind language of protest in growth-oriented police professionalism. In 1949, for instance, the president of the Chinatown Chamber of Commerce responded to a gambling raid conducted by state agents with the careful suggestion that the SFPD could provide white tourists visiting their neighborhood with a better sense of security if it replaced the Chinatown detail with recognizable uniformed police. During the mid-1950s, Dai-Ming Lee, an editor and English-language columnist for the Chinese World, insisted that it was the detail’s autonomous nature—the fact that it was “supreme unto itself ”—that led to its “abuse of authority.” The “plain-clothes sinecures in the Chinatown detail,” Lee stormed, were an anachronism from “the dim, distant past.” Lee noted that two studies—including an “efficiency survey” sponsored by downtown-friendly politicians on the Board of Supervisors—had recommended abolition of the Chinatown detail, and he suggested that Mayor Robinson’s refusal to accept modern management principles stifled broad-based economic growth. “In spite of its lack of advocates,” Lee wrote, “the Chinatown squad continues in existence. We wonder what unseen power makes this possible and what benefits accrue thereby, and to whom. Some day these facts may be revealed, and if and when they are, they should make interesting reading.”

Lee’s insinuations of police corruption and improper management captured the attention of the city’s mainstream press. The same day Lee levied this oblique accusation in the Chinese World, the afternoon-printed San Francisco Examiner included Lee’s quote in its own call for the detail’s elimination.

The San Francisco Chronicle and Police Professionalism

Chinatown’s young entrepreneurs championed police professionalism on the assumption that a professionalized police chief would initiate top-down reforms serving the color-blind interests of the city’s families. However, the professionalism campaign’s vague approach to law enforcement strategies also enabled it to attract constituencies less invested in the city’s traditional family values. During the early 1950s, a collection of young, white San Francisco Chronicle journalists who frequently reveled in the city’s bawdy reputation emerged as the local professionalism campaign’s most public proponents.

The Chronicle entered the 1950s as a third-place afterthought among the city’s four major newspapers. In terms of both circulation and political influence, the San Francisco Examiner towered over the local media landscape. Proclaiming itself the “Monarch of the Dailies,” the Examiner attracted the favor of select politicians by boosting the officials’ public image and supplying them with information critical for the policy-making process. As the political scientist Frederick Wirt explained, passing a single policy item through San Francisco’s convoluted government (the city maintained 65 separate elective offices and 29 boards and commissions) often required local politicians to broker deals with an array of boards, commissions, and departments. Politicians could maximize their powers of persuasion in these negotiations if they understood the interests motivating each of these government bodies. Local journalists, Wirt observed, often possessed just this sort of knowledge, and political elites thus respected reporters as important policy-making allies.

The Examiner used its dominant circulation and news-gathering abilities to win influence in City Hall, then employed that leverage to affect appointments within the SFPD. During the late 1940s and early 1950s, for instance, the mayor’s Police Commission always appointed the chief of police nominated by Bill Wren, the Examiner’s managing editor. In a self-reinforcing fashion, the newspaper then used the loyalty of police officers, who gave the Examiner scoops on newsworthy crimes, to expand its news-gathering prowess over its competitors. “The good old Ex,” a Chronicle editor later grumbled, “owned, body and soul, the police department and the mayor’s office.”

During the early 1950s, a small cluster of ambitious journalists and editors at the San Francisco Chronicle saw an opportunity to challenge the Examiner’s favored position by advocating police professionalism. This campaign took off in earnest in 1952 when the Chronicle’s owners promoted Scott Newhall to the editor’s chair. Newhall had joined the newspaper in 1935 as a photographer and quickly climbed his way into the supervisorial ranks. Between 1952 and 1970, Newhall oversaw the Chronicle’s day-to-day operations and controlled the newspaper’s editorial voice. In a spectacular run, the Chronicle gained ground on the Examiner until it surpassed it in circulation by 1960.

Newhall cut into the Examiner’s sales and political clout with two inter-related strategies. First, the young editor attracted San Francisco readers by developing a reporting style that he felt reflected the readership’s culture. Describing the Chronicle’s editorial approach during the late 1960s, two media scholars wrote, “It is unlikely that there is another group of newspaper executives anywhere in the country—with the possible exception of those running the New York Times—that is so conscious of its audience, and of the effect of its newspaper on that audience.” Monopolizing and unleashing the Bay Area’s best writing talents (including, for most of this period, Herb Caen, the dean of local columnists), Newhall encouraged his writers to convey their own reactions to events in their stories. This approach produced what one Chronicle editor described as a “cult of personality” within the newspaper’s pages.

Newhall undercut the Examiner’s power from a second direction by exposing corruption within the SFPD and advocating for police professionalism via exposés on the “Blue Gang” atop the police force. Newhall hoped these reforms would “liberate the mayor and the police department” from the Examiner’s machinations. The scandal reports also served Newhall’s first goal of projecting his vision of the city’s culture. In the newspaper’s various corruption investigations, the Chronicle repeatedly characterized police payola, rather than the criminal activities permitted by the payoffs, as the true threat to the city’s welfare. The newspaper often portrayed the exposed underworld operations as exciting sources of entertainment. In 1953 the Chronicle series “Tenderloin: The Secret City” spent a week and a half railing against police extortion while introducing its readership to the city’s red-light district with amused winks and nods. Each report came with a boxed glossary defining catchy underworld terms and phrases such as three striper and drop the junk. Like the Chinatown entrepreneurs, the Chronicle hoped to use police professionalism against the city’s traditional machine. But while Chinatown’s entrepreneurs assumed that centralized policing would reinforce the traditional leadership’s avowed mores, some of the Chronicle’s professionalization advocates appeared unconcerned by the prospect of more relaxed cultural codes.

Managerial Growth Advocates and the Police Professionalism Coalition

During the late 1940s and early 1950s, San Francisco supervisor George Christopher drew together Chinatown’s entrepreneurs, the Chronicle’s young staff, and a range of other constituencies to form a broad and powerful political coalition around the issue of police professionalism. The son of Greek immigrants and a product of San Francisco’s working-class South of Market neighborhood, Christopher amassed a small fortune in the dairy industry prior to World War II. In 1945 the “wavy-haired dairyman” stepped into the political arena with a run for the Board of Supervisors. Because he lacked strong connections within the city’s patronage networks, he found it easy to campaign against them. Christopher’s clean-government message won him a seat on the board, and from there Christopher played, according to one supporter, “the role of the young Turk, charging headlong at every municipal sin he could unearth.”

Christopher aimed most of his fire at the venal ties binding the underground economy, the SFPD, and the Robinson administration. Similar to Lee, he insisted that corrupt policing failed to serve either the citizenry’s financial interests or its social mores. When machine-politics defenders claimed that tolerance for gambling and prostitution benefited San Franciscans by luring convention dollars into the city, Christopher scoffed, “Some people say… that an open town would create prosperity. But… prosperity doesn’t mean prosperity for a half-dozen gamblers and racketeers. It is only prosperity when all the men, women and children of San Francisco are in it.” Machine politics, Christopher further intimated, threatened the family. “All these so-called open town elements care about,” Christopher warned, “is the fast buck. They don’t care where they get it—whether it’s from your daughter or the kid next door.”

Through police professionalism Christopher hoped both to illustrate the efficacy of his managerial governing style and to take the first steps toward downtown redevelopment. An honest chief with the authority to end the unscrupulous relationship between the mayor’s office and the Hall of Justice, Christopher vowed, would free city officials to serve the citizenry’s supposed common interests. He promised that these new circumstances would allow expert planners in City Hall to lower tax rates, clear slums, revivify the port, and draw Major League baseball into the city. By contrast, Christopher said very little about what the police chief would do with his newfound freedom from payola. Voters were unbothered by this haziness; in 1949 and 1953, Christopher received more votes for supervisor than any other candidate (an astounding 73 percent of the electorate voted for him in the latter election), and the young politician served as the board’s president for the first half of the 1950s.

In 1955 Christopher ran for mayor against George Reilly, a union-friendly machine Democrat whom one Christopher supporter labeled “an old-time fixture of the city’s political trough.” (Because San Francisco maintained a partisan election format, Christopher could avoid compromising his common-good posturing with a party identification. He finally introduced himself as a Republican in 1958 when he ran for United States Senate.) Christopher placed police reform at the top of his campaign platform, and with the backing of downtown business leaders, the Chronicle, and Chinatown’s young entrepreneurs, he won the 1955 election by a greater margin than any candidate in San Francisco history. Understanding police reform as the key to his growth agenda, the mayor-elect anticipated, “The success of my administration depends a great deal on the success of the Police Department.”

Christopher looked to consolidate police power in the hands of an honest police chief, and an outside raid by federal Treasury agents against six bookmaking establishments, conveniently conducted three days before his inauguration, provided him with his opportunity. After inveighing against corruption in the department-wide assembly at Commerce High School, Christopher brought together representatives from the Examiner and, for the first time, the Chronicle for a meeting to choose a new police chief. Christopher and his advisors emerged from the gathering with a selection that thundered through the SFPD’s command ranks. Traditionally, the chief was chosen from among the SFPD’s pool of captains, but Christopher’s Police Commission now selected Inspector Francis “Frank” Ahern, an officer with a patrolman’s civil service rank. Chief Ahern then doubled down on this break with custom by tapping Thomas Cahill, another patrolman-ranked inspector, as his deputy chief.

Ahern was the San Francisco police officer most associated with professionalism. During the early 1950s, politically savvy officers across America were reaching out to up-and-coming managerial growth advocates through vigorous campaigns against potential sources of graft. In Philadelphia, for instance, Frank Rizzo won a name for himself among professionalizers through his drives against prostitution and gambling rackets. In 1967 he was appointed Philadelphia’s police commissioner. In San Francisco, Ahern earned his professionalism bona fides in a similar manner. During the late 1940s, District Attorney Edmund “Pat” Brown was busy establishing himself as a friend of managerial growth advocates through a drive against abortion clinics operating under the sanction of corrupt police officers. Brown needed a police officer willing to break ranks and conduct his raids, and he found an eager ally in Inspector Ahern. Ahern then captured the imagination of the press when, during his bust of the city’s largest abortion clinic, he turned down an offer for a $280,000 payoff.

Following the clinic crackdown, Ahern continued burnishing his reputation in the SFPD’s elite homicide squad. He hand-selected the young and promising Cahill as his partner, and the duo made headlines with their investigations of gangland murders. In 1950 they earned national attention for their testimony before Senator Estes Kefauver’s Committee to Investigate Organized Crime in Interstate Commerce. The senators were so impressed with Ahern’s and Cahill’s grasp of national organized crime networks, criminal enterprises with little presence in San Francisco, that the committee borrowed the two officers for the next six months as it continued touring other parts of the country.

San Francisco’s machine officials attempted to use and contain Ahern during the early 1950s. When the SFPD’s police chiefs needed to respond to corruption scandals with short-term drives, they turned Ahern and Cahill loose. In November 1955, however, Ahern recognized in Mayor Christopher’s election a chance to vault over his commanders. He thus accepted a secret invitation from federal Treasury agents to participate in their January 1956 gambling house raids. After Ahern then received his appointment as chief, he quickly established his authority over his former commanding officers with a massive shake-up. Most dramatically, Ahern transferred his politically formidable former supervisor, the chief of inspectors, to a sleepy “fog belt” posting as captain of Taraval Station.

Regarding police professionalism as a two-man arrangement involving himself and the chief, Christopher reaffirmed his own personal incorruptibility. “I was in office only a short while,” the mayor later advertised, “when a man came into my office and with hardly more than a hello, hinted he’d pay me $150,000 for gambling concessions. I booted him right out the door.” Christopher also claimed that he had turned away a police captain who approached him and offered, “I can play it any way you want. I can keep things opened up, or I can close them down—whatever you say.” Christopher assured the public that his personal determination to stay out of police affairs would allow his honest police leader to create “a streamlined, efficient department whose integrity was unquestioned.” Confident in Ahern’s power to impose his will on the police force beneath him, Mayor Christopher trumpeted, “We’re in business.”

Managerial Growth Politics and the Common Good

For managerial growth mayors like Christopher, police professionalism served a double purpose. On one hand, clean-government officials used police reforms to eliminate the graft hindering their redevelopment agenda. On the other hand, elites like Christopher exploited professionalism to present themselves as guardians of the public good. Managerial growth administrations across the country—in cities as wide-ranging as Los Angeles, Chicago, Denver, Oakland, Boston, and Atlanta—made police professionalism the dominant police model of the 1950s.

As managerial growth advocates achieved power and instituted police professionalism, their faith in top-down administrative reform freed police departments to enact a wide range of seemingly contradictory law enforcement strategies. In San Francisco, for instance, Christopher and his new police leaders proved comfortable operating machine-era and professional policing strategies side-by-side. Officers participating in either approach, Christopher, Ahern, and Cahill agreed, would reliably follow the will of the clean-government leadership.

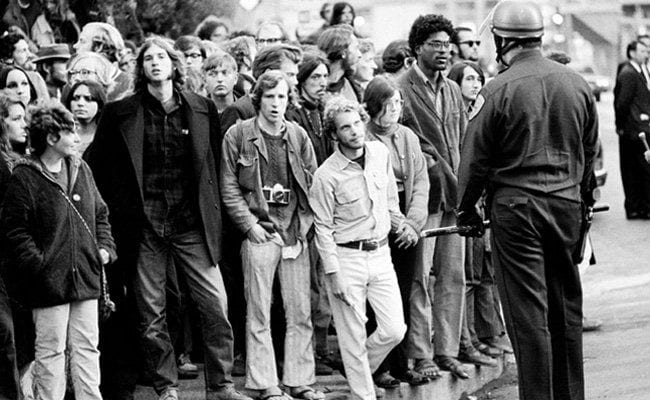

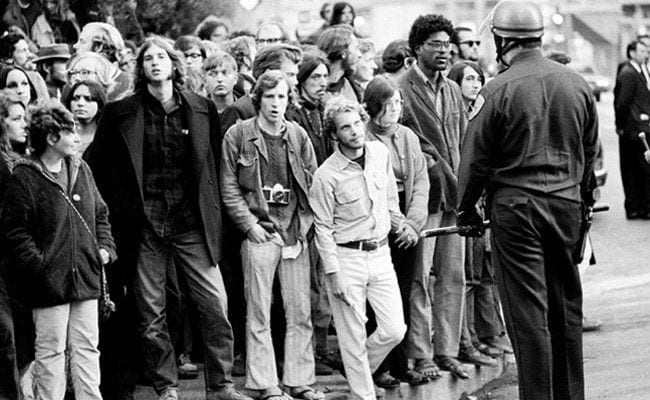

Figure 4. Homicide bureau inspectors pose with evidence seized during a gambling raid. During the early 1950s, politically savvy police officers raised their status among managerial growth advocates by cracking down on gambling houses and other sources of police payola. Evidence for how clean-government law enforcement served as a launching pad for a generation of police officials, this photograph includes the SFPD’s next three police chiefs: Frank Ahern (second from left), Thomas Cahill (far left), and Al Nelder (far right). Michael Maguire, the commanding officer at the 1960 anti-HUAC demonstration at City Hall, is also present (fifth from right). April 23, 1955. (Reprinted with permission, Bancroft Library, BANC PIC 1959.010—NEG PT III 04–23–55.7: 6.)

The new administration’s willingness to maintain machine-era policing strategies came as a rude shock to the young entrepreneurs in Chinatown. When Christopher took office in 1956, both he and Chinatown’s business leaders sought to make Chinatown a demonstration project for the democratic potential of managerial growth politics. The mayor and the entrepreneurs agreed to integrate Chinatown into the growth agenda by transforming the neighborhood into a tourist destination for white families. Within the first thirty days of his administration, the mayor appointed Chinese-American entrepreneurs and landowners to various Chinatown development and tourism advisory committees, set plans for a new Chinatown parking garage, and approved the construction of a Grant Avenue archway marking the tourist entrance into the neighborhood. Chinatown’s development, Christopher and the neighborhood entrepreneurs hoped, would illustrate that citizens who accepted a development strategy reinforcing the city’s color-blind, family-oriented values could expect to enjoy a civic voice and personal enrichment.

Chinatown’s young business elites assumed that Mayor Christopher’s avowed commitments to color-blindness and consolidated authority in the upper ranks of government would lead to a final abolition of the Chinatown detail in their community. Months before Christopher took office, Mayor Robinson’s administration had cheered Chinatown entrepreneurs when its SFPD command staff, like the SFPD leadership under the previous administration, eliminated the Chinatown detail. Robinson’s police chief was likely hoping to either ingratiate himself with Christopher or deny the new mayor payola, but he explained the detail’s abolition by equating equal citizenship with uniform law enforcement. Chinatown’s residents, the Robinson’s chief declared, were “Americans of Chinese ancestry [who] should be treated as Americans.” When Christopher entered office, Chinatown spokespersons expressed their hope that the detail would remain demobilized. After all, Lee reminded his English-reading audience, the detail’s “corrupt practices” had worked against the interests of “the majority of law-abiding citizens.”

A month and a half into Christopher’s first term, the mayor and Chief Ahern encouraged white residents and tourists to attend Chinatown’s Chinese New Year Festival by banning gambling and fireworks and promising, in the Chronicle’s words, a “safe” and “honest” celebration. Chinatown business leaders swallowed these proscriptions, but other Chinatown residents proved less interested in remaking their neighborhood into a playground for white parents and their children. During the New Year parade, locals brazenly ignited fireworks and rained verbal abuse down on Chief Ahern’s parade car.

Christopher and Ahern immediately reactivated the Chinatown detail. The mayor assumed that Ahern would be able to direct all units under his command—even decentralized and formerly corrupt details—toward honest and color-blind law enforcement policies. The reconstituted squad quickly engaged in a series of raids against neighborhood gambling sites, and, as City Hall and SFPD officials predicted, the detail remained committed to this drive against open gaming. Indeed, by the end of the 1950s, the mainstream press used pictures of Chinatown detail officers to underscore the neighborhood’s new, law-abiding image. An extended San Francisco Examiner series on local policing, for instance, limited its depiction of the Chinatown detail to a single photograph of two squad members calmly supervising a legal game of mah-jongg. Chinatown entrepreneurs accepted the trade-off of dissimilar state services for economic gain. Recognizing that detail officers now served the neighborhood business community’s financial interests by rejecting payola, the Chinese World dropped its half-decade–long campaign against the detail and instead offered approving coverage of the Chinatown detail’s gambling house busts.

Managerial Growth Politics and the Common Good (cont’d)

Ahern relied on machine-era policing approaches because he was confident of the transformative power of his personal honesty, but also because he lacked the creativity to devise modern, professional strategies. In 1958, while attending a Labor Day home game of the newly arrived San Francisco Giants, and during a dramatic play at the home plate, Ahern suffered a fatal heart attack. For his replacement, Christopher turned to Cahill. The new chief possessed Ahern’s willingness to turn down graft, but he also brought a keener tactical and administrative mind to the office. Under Cahill, the SFPD leapt into the van of the nation’s police professionalism movement.

Cahill was born in Chicago, but he spent his first seventeen years in Ireland with his mother. After she passed away in 1929, Cahill returned to the United States to settle close to relatives in the Bay Area. He worked for the next thirteen years as a farmhand, a cement hauler, an elevator operator, and an ice deliveryman. In this final position, Cahill’s leadership potential emerged, and he was elected to serve as the Ice Wagon Drivers Union representative to the powerful San Francisco Labor Council. By now, Cahill had grown into a striking and magnetic figure. Tall and broad-shouldered, Cahill charmed with his blue eyes, red hair, and Irish brogue. In 1942 the thirty-two-year-old Cahill entered San Francisco’s Police Academy, where his final class yearbook identified him as “most likely to become Chief of Police.” Cahill not only made good on that prediction but went on to serve as the longest-tenured SFPD chief in San Francisco history.

Elsewhere in the country, police professionalism advocates were arguing that the nation’s newly reformed police departments could now serve the common good through preventive policing. Criminology scholars, such as the University of California’s O. W. Wilson, and prominent police leaders, including Police Chief William Parker in Los Angeles, urged police departments to begin seeking out criminals rather than waiting for citizen complaints. Just weeks after his appointment, Chief Cahill introduced Operation S as a novel preventive approach to violent crime. Cahill explained that the S stood for saturation, and he promised a professional program based on centralized personnel authority and putatively color-blind, scientific data sets. Operation S leaders at the Hall of Justice used crime statistics to identify criminal “hot-spot” neighborhoods, and then, twice a week, they flooded these hot spots with roughly fifty police officers handpicked from the district stations.

In December 1958 a Chronicle feature offered a typically effusive description of Operation S’s top-down arrangement. The report began by explaining how Deputy Chief Al Nelder personally briefed the participating Operation S officers. These meetings rarely included concrete information beyond a hot sheet enumerating the licenses of stolen automobiles, but the wowed Chronicle compared the orientations to “an evening in night school.” After officers received this preparation, the newspaper continued, the police headed out as “shock troops” to not only solve crimes but prevent them. When police encountered citizens on the street, the article explained, officers employed vagrancy charges against those whom police believed were ready to break the law and compelled the remainder to fill out identification cards. These identity cards, the Chronicle concluded, then became “tactical weapons” by providing police with a ready list of suspects for any nearby crimes.

Operation S served managerial growth advocates by establishing rationales for large-scale redevelopment. Christopher’s opposition to government welfare had initially made the new mayor wary of large redevelopment projects necessitating federal aid. He had therefore initially pursued small, privately funded projects, such as the construction of the Chinatown tourist-entrance archway. By 1958, however, the mayor was considering an upcoming reelection race alongside the continued demands of his downtown backers for access to federal redevelopment funds. Christopher thus relented, and Operation S now helpfully taught citizens to identify planned zones of redevelopment as crime hot spots in need of rescuing.

From the start, Operation S commanders and the SFRA’s large-scale planners both set their sites on the Fillmore District, a predominantly black neighborhood bordering City Hall. In December 1959, Ernest Lenn, a San Francisco Examiner journalist, recounted an evening he spent shadowing two Operation S officers through “the neon-lit, trouble-spot Fillmore area.” Beginning his feature with a stock description of Deputy Chief Nelder’s orientation, Lenn recounted how the officers’ patrol car rolled into the Fillmore, where “slum clearance” had “leveled a swath of drab, ancient buildings.” The city had replaced the former neighborhood with “many-storied housing projects” that looked to Lenn like passing “hospital ships in wartime.” However, the redevelopment campaign remained incomplete: other “slum buildings still stand, waiting patiently for the end.” Lenn believed that until the clearance was finished, Operation S officers were necessary guardians against violence. His article recounted how, over the course of the evening, the two patrol officers prevented a rape, issued a vagrancy arrest to an armed former convict “lurking” behind tall bushes, and questioned a variety of other men.

Both Operation S and redevelopment, managerial growth proponents averred, represented clear examples of the city leadership’s ability to promote a colorblind common good. This service to broader shared interests, downtown growth advocates concluded, allowed the city to look past questions of individual civil liberties. “The respectable citizen,” District Attorney Thomas Lynch explained, “shouldn’t object to being stopped and questioned politely if he realizes it’s for his own protection.”

Operation S established San Francisco as a national leader in police professionalism. Television shows ranging from The Lineup during the 1950s to The Streets of San Francisco two decades later celebrated the SFPD for its combination of technical proficiency, academic expertise, and tough-fisted policing. Meanwhile, managerial growth administrations in other cities began recognizing that they too could employ putatively centrally orchestrated policing arrangements to rationalize increased police pressure. In 1960 the Chicago Police Department used Operation S as a point of inspiration when it launched stop-and-frisk policing. Over the next decade, growth-oriented cities across the nation followed San Francisco’s and Chicago’s lead with their own programs of “aggressive preventive patrol.”

The Discovery of Discretion

Mayor Christopher’s broad electoral coalition and the SFPD’s mixture of machine-era and professional policing strategies all rested on the assumption that state institutions served as reliable extensions of the city leadership’s will. But just as Mayor Christopher achieved power through police professionalism, criminologists made a startling discovery with the potential to undercut Christopher’s conception of governance. Policing scholars who observed officers on the street slowly recognized that even professional police did not act as simple automatons of the department and city leadership; instead, officers used and enjoyed tremendous amounts of discretion.

The discovery of discretion began with a 1956 American Bar Association (ABA) study of urban police activities. The ABA initiated this national investigation into day-to-day law enforcement to better understand the police corruption garnering attention from managerial growth advocates. From the start, ABA investigators uncovered widespread evidence of police misbehavior. One field report, for instance, recounted an incident in which police interrogated a suspect with a fake polygraph machine fashioned from a kitchen colander. Revelations of police wrongdoing were nothing new; a range of studies during the 1930s—including San Francisco’s Atherton investigation and the congressional Wickersham Report—found endemic police criminality in urban police departments. These earlier inquiries, however, assumed that police malfeasance arose from feeble leadership and partisan outside interests corrupting officers who suffered from weak morals. The notion of police discretion played little role in this story. O. W. Wilson’s Police Administration (1950), the so-called bible of professionalism, advocated top-down reforms without employing the term discretion once.

The ABA researchers, however, viewed instances of police criminality in the context of all the officers’ day-to-day activities. In this new light, the surveyors recognized that the practice of law enforcement in the United States usually rested on the subjective decision making of individual officers. Law enforcement officials, the study found, then sometimes used that discretion to pursue their own institutional interests. Managerial growth proponents were soon forced to confront the fact that the administration of law enforcement did not parallel the governance of redevelopment. Whereas redevelopment officials in San Francisco plotted out neighborhood razings and construction projects with relative exactitude from SFRA board rooms, the Hall of Justice’s police policies were always mediated through an array of considerations made by the department’s 1,800 officers. This realization raised the question of whether police professionalization necessitated more than a consolidation of power at the upper ranks.

By the late 1950s, the survey’s new interpretation of discretion filtered into the public through articles and conferences. California scholars played a prominent role in the ABA research, and thus an awareness of police discretion hit the Golden State early. For careful observers of the SFPD, it became clear that officers involved in policing programs like the Chinatown detail and Operation S relied on their own subjective determinations. In Chinatown, a new generation of activists began asserting that some Chinatown detail officers used their autonomy to disregard intraneighborhood violence. These community spokespersons believed that City Hall leaders and Chinatown businesspeople tolerated the squad’s discretionary underenforcement of the law because reports of resident-on-resident violence hurt the area’s reputation as a “safe and clean” tourist spot for white families.

Operation S, by contrast, created institutional incentives encouraging officers to use their discretion to engage in aggressive law enforcement. The twice-a-week program offered uniformed officers the thrilling opportunity to play the role of inspectors. “We weren’t hemmed in by boundaries,” Patrolman John Mindermann recalled. “We were thrown into the whole environment of the city to do whatever the hell we wanted.” Patrol officers understood, moreover, that distinguished work on this special assignment could earn them a transfer into the vaunted Inspectors Bureau. Thus, as participating police pursued arrests, one patrolman recalled, the sense of competition among officers was “open and raw.”

Mayor Christopher and the managerial growth proponents ultimately appreciated the subjective policing encouraged by Operation S. Autonomous discretion strengthened the participating police officers’ ability to maintain San Francisco’s traditional boundaries of citizenship. Managerial growth advocates gave little public consideration to the workplace motivations of police officers but assumed that white male patrol officers would follow the city leadership’s color-blind family values. Christopher and Cahill therefore trusted these officers to use their discretion to enforce the city’s cultural, sexual, and racial norms.

The Examiner’s Lenn illustrated these assumptions in his report on his night shadowing two Operation S officers. The two patrol officers, Lenn related, spent the evening sizing up people on the street but then came to a stop when they encountered “two Negroes.” The two Fillmore residents made themselves suspicious to the officers, Lenn explained, by wearing “windbreakers and dungarees” and “loitering” in the entryway of a residence. To Lenn and the officers it was obvious that these black men were exhibiting dangerous intentions through their clothes and behavior. Thus for Lenn it went without saying that the officers had used their discretion to serve the common good when they compelled the two men—and eight other residents before the night was over—to show their identification papers and “fill out Operation S interrogation cards.” The fact that the officers eventually dismissed all ten of those men without charge did not dissuade Lenn from presuming that the patrol officers’ discretion served “to bolster the thin blue line” between order and chaos.

Conclusion

During the mid-twentieth century, downtown elites in cities across the country wrested power from traditional machines through managerial growth politics. Seeking to sideline working-class voters, big-business representatives argued that the city could protect the traditional standards of citizenship and promote widespread economic growth by consolidating governing power into the hands of supposedly dispassionate experts like themselves. Police professionalism served a double purpose in this campaign: the reforms squelched the machine’s payola, and the program’s abstract promises of top-down, common-good governance won support from an array of constituencies maintaining different understandings of the city’s interests.

As Mayor Christopher and the SFPD’s new leadership entered office promising law enforcement reform from above, scholars discovered that much of police policy was made on the beat. Recognizing how discretion-oriented programs like the Chinatown detail and Operation S served the redevelopment agenda, managerial growth advocates scrambled to rationalize the rank and file’s broad prerogatives. Managerial growth proponents ultimately justified discretion by insisting that the city’s officers could be trusted to use their powers in the service of the citizenry’s shared color-blind, traditional family values.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)