If you’re going to San Francisco

Be sure to wear some flowers in your hair

If you’re going to San Francisco

You’re gonna meet some gentle people there

Scott McKenzie’s iconic song evokes the image many associate with San Francisco: a liberal, tolerant, permissive city with a laissez-faire attitude toward a plurality of lifestyles, art, and sexuality.

But it wasn’t always that way. The personalities of cities, like people, are susceptible to change, even if that process takes decades rather than years. And as change occurs, it provokes reactions: there is backlash and counter-movements as the many political and social institutions that comprise a city’s identity struggle with the prospect of change.

Christopher Lowen Agee’s masterful portrait of a city in the throes of social change adopts an innovative angle, looking at it from the perspective of policing. His snapshot of time happens between 1950 and 1972, a period in which San Francisco uneasily adopted the cosmopolitan liberal identity with which it is often associated today. But how did that happen? How does the personality of a city change? And if the police see their role as one of protecting a city’s values and identity, how do they respond when these things are in transformation?

Agee’s historical and social analysis of this period reveals that the response of the police to social change – even when they were resisting it – often did as much to encourage change (sometimes unintentionally) as it did to slow it, and contributed a great deal toward shaping the eventual type of cosmopolitan liberalism that resulted. His book is not a simplistic chronology of people and events, but rather, an analysis of policing in relation to, and in engagement with, other social movements and political and social institutions.

For the reader who is not a specialist in policing and police history, the book is fascinating in that it reveals the complex struggle over identity, purpose and principles that police officers and police institutions face on a regular basis. It reveals a human side to the mirrored masks; a human side that is fraught with doubt and uncertainty even while it exudes a public demeanor charged with no-nonsense, confident authority.

It also reveals policing as a social institution inseparable from the other institutions that surround it: electoral politics, journalism, social movements, the arts, business communities and even bar scenes. By zeroing in on a single institution – policing – Agee in fact manages to demonstrate the dynamic, vibrant and interconnected nature of the network of other institutions in which it is embedded. It’s a fascinating approach and offers a wealth of observations and insights for the student of urban environments and social movements alike.

So how did an innately conservative institution like the San Francisco Police Department eventually come to terms with the cosmopolitan atmosphere of liberal pluralism that San Francisco came to be known for? Not without a great deal of struggle and difficulty.

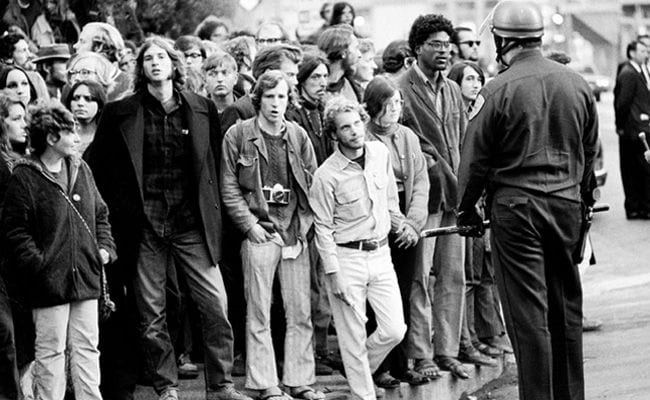

Agee selects a series of case studies – the beatniks and bohemians of North Beach; Chinatown businessmen; the gay bar scene; sexually explicit artists; racialized gangs; Haight-Ashbury hippies and community activists – to illustrate the changing ways in which police came to engage with these groups who posed challenges to the dominant social order and status quo (and how they, in turn, engaged with the police).

A constant undertone is municipal electoral politics: politicians seeking election in a democracy must be sensitive to changing public attitudes and social mores, and political supervision of policing entailed a complex relationship between the police and the politicians. ‘Tough-on-crime’ crusades are often popular, but public support can also swing to the side of those targeted by such crusades when they become excessive.

The other underlying theme is the tension between top-down, centralized professionalism in policing, versus the personal discretion officers traditionally exercised on the streets. Police are often put in situations which require them to exercise personal on-the-spot judgement and discretion – especially in an era prior to advanced communications technology – and while personal discretion enabled many officers to ‘keep the peace’ in the streets, it also opened the door for less scrupulous officers to succumb to the lures of personal bigotry and bribery.

Agee’s case study of the gay bar scene offers one such example. While homosexual acts were illegal, many officers accepted bribes to allow gay bars to operate. Before the advent of technocratic, managerial-style politics, many politicians even relied on such payouts to prop up their electoral campaign funds – ‘gayola’, as it came to be known. Indeed, police often preferred to avoid high-profile gay bar raids, as these served to illustrate the awkward fact that a burgeoning gay scene existed at all, gradually reinforcing the normalcy of such a scene.

However as young, technocratic politicians began to wrest control from the old-school dynasties that had dominated city politics, these reformers began cracking down on police corruption and permitting charges to be laid against officers who accepted bribes. The result, while freeing gay bar operators from the financial burden of payouts, was that those bars also lost the institutional protection these bribes afforded. As police raids increased in the absence of payoffs, bar owners found themselves more often in court. But the effect of this, paradoxically, was to reveal to the public that gay bar owners and patrons were not fearsome-looking criminals but respectable businesspeople dressed in suits and ties.

Gay bar owners responded by forming their own networks, conducting surveillance of police stations and photographing undercover officers so as to identify them when they showed up in their bars. They invited journalists to meetings where they discussed the challenges they faced, gradually invoking sympathy and support from the more liberal papers. Aggressive police raids worked to their advantage, allowing them to present themselves as civil rights victims.

The image this gradually revealed was of a ‘respectable’ (often white) gay middle-class and politicians found themselves increasingly hard-pressed to explain why they were persecuting these hard-working entrepreneurs. The formation of gay and lesbian bar networks such as the Tavern Guild also revealed the political possibilities of courting a gay and lesbian vote. The result of these complex processes – described in much greater detail in Agee’s book – was a gradual cessation of police targeting of gay bars, followed eventually by changes to the laws on which police enforcement had been based.

All of this illustrates the complex social and political dynamics underlying police practices. It reveals changing conceptions of citizenship (who is considered an acceptable part of the community?) and threat (which is a bigger threat to the stability of the community – non-traditional sexual lifestyles, or police corruption?).

Politicians, historically (and even today) rely on allowing police officers a broad degree of discretion in order to enforce the unwritten rules and social codes that are dominant in society (in ’50s-’60s San Francisco, this meant police harassment of interracial couples, of same-sex dances, of bearded hippies who spent the day at a bagel shop reading poetry instead of working). Yet in seeking to stamp out police corruption, politicians had to centralize policing and curtail officers’ discretion. This afforded a window of opportunity for those seeking public legitimacy – the gay middle class, Chinatown business entrepreneurs, etc. – to align themselves with reform efforts, and to point the finger at police (and political) corruption as being the greater threat to a stable and prosperous society.

Agee deploys the same scrupulous detail in other chapters looking at the racialized politics of policing in Chinatown; dealing with bearded beatniks; policing in economically depressed and racialized communities, and more. He deploys an impressive grasp of the wide range of complex social processes that interacted with each other as social mores changed.

In the end, even the police found themselves influenced by these processes and begin to form competing, politicized labour organizations to fight for their own voice amid the cacophony of sectarian interests. This would eventually lead to surprising outcomes, such as temporary alliances between police associations and hippie communes to oppose city hall plans for closing neighbourhood police stations.

The Streets of San Francisco is a fascinating study, if a complex and scholarly one. But the narrative is not inaccessible, and the impeccably researched story it presents is an engaging one. It provides an interesting and under-examined insight into the cultural dynamics of the ’60s and ’70s, revealing that the police were not just an enemy of social change, but were often as much a part of it as the social movements they faced down in the streets.

The dynamics Agee analyzes in San Francisco are common to many large North American cities, and as such they help us better understand how and why today’s institutions of law and order developed. By negotiating their complex and fraught terms of engagement, together the police and the cosmopolitan liberal community coalitions “ultimately reconceived definitions of crime, the boundaries of citizenship, and the proper shape of government in an urban democracy.”

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)