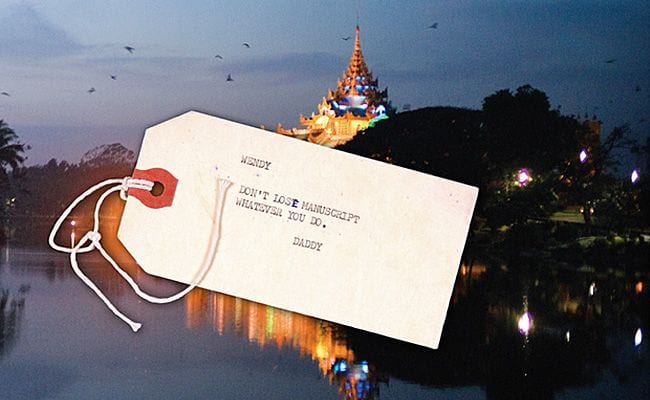

Long after he entrusted them to her, and some years after his death, Wendy Law-Yone finally retrieved her famous father’s autobiographical notes and manuscripts from a box in her closet and began reading. The intertwined story of their lives, recounted in A Daughter’s Memoir of Burma, sees Wendy coming to terms with her father and his complex history and legacy, as well as with her own complex relationship towards the troubled country she grew up in.

Those seeking a political memoir, or a quick lesson in Burmese history, will be disappointed. This is a much more personal narrative, which strives not to illuminate the politics and history of Burma, but rather to reveal the personalities, history and relationships of the Law-Yone family. Insofar as Wendy’s father, Edward Law-Yone, played a key role in Burmese history, the book inevitably engages with pivotal moments and events in that history. Yet it is above all a personal account, charting the complicated relationships of a family through times of prosperity, struggle, persecution and ultimately exile abroad.

Following a series of colourful, adventurous escapades during World War II, Edward Law-Yone launched what’s been described as Burma’s leading English-language newspaper, became a central figure in Burmese post-independence politics, spent five years in prison for challenging Burma’s military dictatorship, and finally escaped the country and together with other exiles organized armed resistance to the regime. He eventually gave up his role in the struggle, and joined other members of his family in the United States. There he spent the remaining years of his life: from the struggle to preserve freedom and democracy in Burma, he turned his energies to the struggle to preserve a family that found itself facing all the pressures and challenges of distance, illness, relocation and adjustment.

But even if Edward Law-Yone is the most famous character in the book, ultimately this is his daughter’s memoir. She tells the story of her own childhood and young adulthood in a Burma undergoing rapid social and political change: liberation from occupation and colonialism, independence, an all-too-brief effort at democracy, and finally the coups which ushered in an era of military dictatorship from which the country has still not fully emerged.

As Wendy grew to adulthood, her father went from national celebrity to prisoner of state; when she too began encountering state repression (she was barred from university because of her father’s activism) she tried to flee the country, but was apprehended and briefly imprisoned, as well. She was eventually released, and allowed to join her American husband in Thailand (from there they eventually re-settled to the US, returning at intervals to Asia).

While an interesting and engaging read, the book is at times disconcerting in its alternation between fast-paced political events, and long stretches of attention paid to the quotidian detail of everyday life. There is at times a clash between the trenchant political reality of detentions, assassinations and looming repression, and the long passages of uneventful home life which intersperse them: snorkeling in lakes, midnight romantic trysts, tales spun to schoolyard friends. This sometimes trips up the momentum of the work as a political memoir recounting Burma’s post-independence lurch toward military dictatorship.

But in reality the book is a memoir of two people: both Wendy and her father. What this obscures in terms of political narrative, it enhances in its ability to personalize the key characters. We get a real sense of Wendy’s famous writer-journalist-rebel father, from his daring and offbeat bravado (filching a pass from a military officer in order to sneak into an international diplomatic meeting as a journalist) to the kind indulgence he had for his children (allowing Wendy as a young schoolgirl to accompany him to late night shifts at the newspaper office where she wound up sleeping on the sofa).

What it lacks by way of historical narrative it makes up for in its evocative first-hand description of a country few westerners are familiar with even today. While noting that Wendy’s memories and experiences were those of an upwardly mobile elite (despite stints of poverty, both during and after her life in Burma), they still convey a sense of the beauty, diversity and complex charm of one of Asia’s most complicated, persevering and long-suffering nations.

Readers looking for a succinct chronicle of recent Burmese history would be better directed to other sources. What Law-Yone’s book does offer is a very personal account of how the complicated politics of post-independence Burma shaped the life of one family that was actively embroiled at the heart of events. Much of the book’s action takes place in the US, and chronicles efforts by the various family members to adjust to the differing circumstances of their exile.

Again, bearing in mind that the Law-Yone family was not the average Burmese family, the book offers a very human story of adaptation and change under the duress of political persecution and exile. A touching and sad chapter chronicles the decline of one of the author’s brothers, who succumbed first to mental illness and then to a heart attack which killed him at a young age. The book is, fundamentally, a family history, and the struggle to hold the family together in the years following their departure from Burma offers a very personal and moving human story.

Wendy is an accomplished author with a range of short stories, literary critique, and novels under her belt; she’s a professional journalist, as well. Her deft, skilled writing carries the narrative along and keeps the reader engaged even when the narrative becomes caught up in the less interesting minutiae of daily life (lengthy passages describing her father’s cooking and eating habits, for instance). Occasional excerpts from her father’s personal account – the memoirs which inspired this book – are also engaging and tantalizing, even if they do leave the reader wanting to hear more. One gets the impression her father’s memoirs would make a fascinating read of their own.

Historically, the most interesting parts of the book, and the sections with most historical detail, surround the rise of Edward’s paper Rangoon Nation, and his efforts — taken in tandem with other Burmese exiles — to foment revolution from across the border in Thailand. The organization of a government-in-exile, efforts to fundraise money to purchase arms, personal conflicts between the various members of the resistance movement, and negotiations with the ethnic armed militias that were already engaged in armed struggle against the Burmese state are recounted in riveting detail in the book’s second section.

Wendy’s father threw himself into the resistance movement with the same zeal, ardour and impatient energy that he threw into the building of his newspaper. The rise and fall of the resistance movement led in part by her father makes for a fascinating read. It’s unfortunate that it was limited to two chapters.

One of the most startling parts of the book – and Edward Law-Yone’s life – emerges toward the end. Shortly before his death, he revealed to Wendy the truly complicated nature of the period immediately preceding his arrest by the Burmese government (at the behest of General Ne Win, military dictator and his former friend). It’s revealed that her father’s arrest may have been not only due to his fearless and outspoken politics, but also due to his knowledge of, and complicity in, the extra-marital affairs of the general’s wife. This is a startling revelation, which adds a riveting twist to the end of an already tumultuous tale.

Also fascinating is the final section of the book, sub-titled ‘Homing’. Here, Wendy recounts her visits to the murky borderlands between Thailand, Burma and China. She traveled there in 1989 following the notorious bloody crackdown by the military regime against the nascent democratic protest movement which catapulted Aung San Suu Kyi to fame (and prison). Wendy visited refugee and rebel camps along the border, and even encountered some of her father’s former guerrilla comrades who were still carrying on the struggle deep in the jungles.

She also returned as a reporter writing a piece on the old ‘Burma Road’ between Burma and China, during which journey she rediscovered her grandfather’s home village, and a whole branch of her own family. The story of these visits is coupled with a detective-like quest to find the origins of the other side of her family: the British colonial officer who was supposedly married to her grandmother. What she discovers is a dramatic story that she had not expected at all.

These pieces of reportage are among the best parts of the book. Fascinating and engaging, they allow the book to conclude on a strong, powerful and satisfying note which is rendered all the more poignant by Wendy’s account of her mother’s final days.

A Daughter’s Memoir of Burma is, overall, an engaging and enjoyable read. It’s not a political memoir or history, but it is poignant and touching, and manages to skillfully convey a sense of the personalities involved in these key episodes of Burmese history. As the story of a family struggling to stay together, it transcends the cultural and geographic context of its title. But by choosing this approach to tell her father’s fascinating story, Law-Yone also succeeds in conveying a very different side of Burma than many readers will be familiar with. Instead of the brutal and often depressing face of power and politics, one experiences here the warm passion, humour and hope of a people still struggling to define themselves and their future.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)