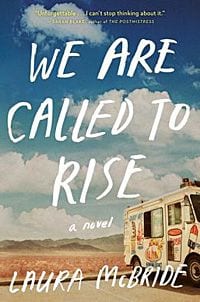

The issue of unwarranted brutality by authority figures has long been prevalent in American culture. It’s one thing to hear Neil Young sing “Four Dead in Ohio”, or catch Spike Lee’s reference to Howard Beach in Do the Right Thing in the wake of an event. It’s another thing altogether, and very rare indeed, for an artist to anticipate a controversy in the fashion that novelist Laura McBride accomplished with her first publication.

Without giving too much of this work away, We Are Called to Rise bears all the hallmarks of a recent tragedy in fictionalized form. Through multiple points of view McBride weaves together the tale of a family ripped apart by a casualty at the hands of the police during an otherwise innocuous encounter. Additionally, the minority characters affected by the violence are marginalized by societal norms. They struggle to retain their identity while fitting into the larger context of a culture unwilling to accept their differences. At the core of We Are Called to Rise is an inarticulate rage that reaches crescendo in an act of unforgivable violence.

Published by Simon and Schuster, We Are Called to Rise received praise and positive reviews from Publishers Weekly, the Library Journal, and BookPage, among others. After the book’s release in June, many reviewers noted how timely its publication was in reference to the glut of returning veterans suffering from the scourge of PTSD. Some weeks later, McBride’s novel would become all the more timely for its eerie similarities to a now infamous event.

Until 9 August of this summer Ferguson, Missouri was a relatively unknown suburb of greater St. Louis. All that would change with the killing of high school graduate Micheal Brown at the hands of the police. The story was immediately picked up by regional news sources, but as opposed to similar incidents in Beavercreek, Ohio or Staten Island, New York, Brown’s incident would generate a much more pronounced response from the public at large.

That night relatives and community members began to gather at a makeshift memorial. A story that began days earlier as regional filler became national headlines after riots erupted from the initially peaceful protests. When Governor Nixon called in the National Guard, news outlets like El Pais, the BBC, and Le Monde carried coverage to a foreign audience. The detainment of journalists and photographers by a hostile police force resulted in the first deployment of Amnesty International on American soil, and drew criticism from the Kremlin over suppression of free speech and the press. The reaction in Ferguson, Missouri, to the sad fate of Brown quickly became the top news story in the world.

In light of the intense media scrutiny and evolving national discussion, I thought it pertinent to investigate the parallels between McBride’s artistic expression and the cycle of violence that has so recently come to national prominence.

McBride is far from a typical novelist. Yale educated, she first pursued a career and family. She didn’t turn toward literary ambition until far later in life than most novelists. At 50 she took a sabbatical from her teaching duties with the firm intention of finally writing a novel. However, We Are Called to Rise wasn’t exactly the story she’d set out to write.

“I wanted to write a novel about contemporary Las Vegas. I drove myself crazy deciding what I wanted to write about, what an agent would be interested in. Then one day I decided I had to start writing no matter what the story was.”

“Las Vegas is a military town. I teach at a community college. One of the benefits soldiers have is education when they come back. As a teacher I have lots of soldiers, and they were very, very much on my mind when I was writing We Are Called to Rise . Very young men and women are sent to war where they are trained to use intense weaponry. They experience things that are so vastly different than what’s going on back here. Then they come home and they are sitting in a class room with people who really have no idea of what they’ve been through.”

McBride speaks with enthusiasm in a bubbly tone that belies both her age and the darkness of the material she has written. From her home in Las Vegas she is confident yet guarded. She reminds me over and again as I steer the conversation towards Ferguson that We Are Called to Rise wasn’t written with an agenda, even if it did anticipate the biggest news story of the year.

“I think human beings, from the time we’re born, are repelled by injustice. And when we’re faced by injustice, it’s hard to see anything else. I mean that’s the story with Ferguson, right? There’s an overwhelming sense that this isn’t the way things are supposed to be.”

“In some smaller way I had felt the same for a long time. Things had happened here that just weren’t right. People should not die when they’re stopped for minor traffic problems. A young man should not die for walking down the middle of the street. I had been paying attention to things like that in my own community for years.”

With this explanation, the author ties together the all too real events on the national news with her work of fiction. The story within We Are Called to Rise wasn’t entirely McBride’s brainchild or flight of fancy. Much like the brutality that came after its publication, there was an original dynamic, another tragic accident, much closer to home.

“There is a way we think about injustice, about the most unimaginably terrible thing that could ever happen to some family, and then it just dribbles across the news. And it’s gone, it just disappears out of the news, out of the media, out of the conversation and it’s gone.”

“I didn’t start writing until four or five years after the (news incident) but it stuck with me. And the fact that it stuck with me meant the story had some dramatic potential.”

So it goes. From the personal knowledge of one who appeared briefly in a news blurb a work of fiction arises. Just as this nearly forgotten episode spent years brewing inside the brain of an author, the national consciousness would be assaulted periodically with tragedies. Cases like Trayvon Martin would surface briefly, their trials containing plots points as intricate as those in Ferguson propelled by a cast of characters as disparate as those in McBride’s book.

“I think these things are happening all the time. There are lots of stories in lots of communities so I don’t think the timing of We Are Called to Rise‘s release was that unusual. Of course, Ferguson is unique in the strength of the response and the attention that has been paid to it, but not in regards to the particulars. I think We Are Called to Rise could have come out at any point and there would be stories to correlate to it.”

“As a middle-aged woman and a mother, it breaks my heart. It makes me sick. I feel a deep, personal connection to that type of event. As a novelist, I’m keenly aware that there are many different facets to a story. My first response is anger or rage over what has happened, there is no way that that is right in the universe that that boy is dead. But I don’t know what happened.”

“It makes me wonder, What are the other stories that go into this? I don’t know if the police officer is a great guy, or a horrible guy. I don’t know.”

And neither does the public. Novels are wonderful vehicles for narrative because they allow for the relation of an event through multiple points of view. The rational mind can then digest the event and weigh the actions of various characters in relation to it. Novels provide the luxury of emotional distance. They may move us tears or inspire us to act, but that reaction comes at no expense to flesh and blood. One simply closes the book and turns off the derogatory onslaught of the evening news. But do we really forget these things?

“People, whether or not they live lives that equate to the stuff of fiction, still experience forms of violence and trauma, or at the very least shock. It’s a huge human experience. If one is attentive to the experience, it builds heart to how much shock and trauma is out there. If there is a lot of violence in art, media, sports, and sadly politics I worry about our cultural ability to stay in community with each other.”

“If we were to face problems more traumatizing — an epidemic, a global crisis of some kind — what does it mean that we haven’t practiced being in community with each other? Instead we express violent competitiveness against each other.”

“Part of the role of art and how much we need art is for its intrinsic value. Certainly, any experience of violence, shock, trauma, grief is huge. Art is how we process the experiences that are too big and overwhelming. We are more human for it.”

“With We Are Called to Rise, I didn’t want to write a cynical novel. But at the same time, the dramatic situation is not resolvable. It could end in great cynicism. So the question was how could I bring out something at the end of this novel where there would be a chance the characters are safe, not well, not OK, not not traumatized, but safe? That would be enough.”

“Resolving everything would just be a cheap shot. Life doesn’t resolve itself very often. A lot of times people just do what the characters of We Are Called to Rise do: they move on. Not move on fixed, or move on better, but just move on.”

There’s no doubt the events over the past several weeks in Missouri have already created a national dialogue. In the past, events that began as outrage and civil disobedience seeped into the general consensus and often developed into legislation.

For the moment there is a relative peace in Ferguson. Passions have abated between the police and protestors. The National Guard has begun pulling out, the arrests and detentions have lulled, the looting has stopped. What remains in addition to the burnt out buildings and faded poster board protestations is an open investigation and the assurance of justice from federal authorities.

Art informs life just as life informs art. At times they arrive atop each other in a metaphysical form of synchronicity. There are certainly parallels between the two as seen in recent trends and McBride’s book. Life, as opposed to art, presents a wealth of questions and very few answers.

To close out the interview I asked McBride if there were any lessons to be learned from her novel. She answered confidently. “That’s for the readers.” On my part it was a trick, a trap to compare that answer to the one given in response to my next question. ‘And are there any lessons to be learned from Ferguson?’

“Of course.” She answered simply.

* * *

Above: WASHINGTON – AUGUST 30: Marchers rally against racism after the shooting death of Mike Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. The march took place in Washington, DC on 30 August 2014 / Image from Shutterstock.com.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)