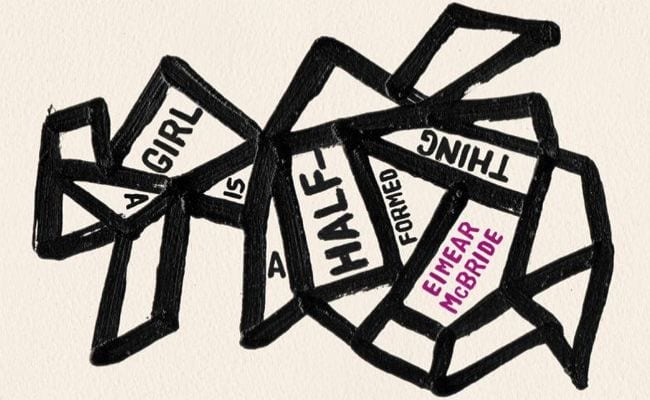

Readers will either love or hate Eimear McBride’s debut novel, A Girl Is a Half-Formed Thing. To date, this raw wound of a book has received nothing but high praise, winning the 2014 Bailey’s Women’s Prize for Fiction (formerly the Orange Prize), and beating out Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch.

A Girl Is a Half-Formed Thing is narrated by a nameless, fatherless Irish girl in barely punctuated, highly charged prose that reads like pre-lingual thinking. Sentences are percussive and forced, often just a few words separated by periods or question marks:

Where’s that father? Mine? Who belonged to was part of me? I think of?

– and –

That station I know it. It’s here. I’m yes that’s fine. Hello.

In this fragmented, broken language, the girl spins out a life: her elder brother was treated for a brain tumor when he was small. The surgery and subsequent chemotherapy left him mentally and physically delayed. Their erratic, deeply religious mother is often abusive. The three live in a remote, nameless Irish village dominated by church life and female gossip, captured in a few tight words, here describing visiting women who come to pray with the girl’s mother. She is the only named character, called Mammy:

They polyester tight-packed womanhood aflower in pink or blue or black or green coats if the day has rain. If in Sunday skirts, every pleat a landscape of their grown-up bodies. Tired. Undertouched.

Brown skin nylons. Leatherette shoes. And they’ll have just a little cup there in their hand. Good for them they like God and Jesus the most.

When the children reach their teens, Mammy decides the family must move. Both children, now in high school, endure teasing at the new school. The girl copes by seeking out anonymous sexual encounters with men of all ages. At age 13, she is raped by an uncle. The two remain locked in a perverse sexual exchange, even as she continues her self-destructive behaviors. She drinks heavily. High school remains a horror of cruelty, while home life is a chaotic place of smothering Catholic piety.

The girl finishes school, escaping to a nameless city and University. She is shocked to find herself homesick in this enormous, polluted place. She makes one friend, a fellow incest victim with a taste for drink and dangerous sex. The two ditch classes, hanging out in pubs and picking up men. A visit home is disastrous; the girl returns to the city and moves in with a friend.

Now that she is of legal age and out on her own, her uncle visits more freely. Her roommate is appalled. The girl, upset by the argument at home and angered by her friend’s judgment, descends into serious alcoholism. Her sexual liaisons become increasingly violent. “I met a man. I met a man. I let him throw me round the bed. And smoked, me, spliffs and choked my neck until I said I was dead.”

It seems the novel could grow no unhappier when the brother, whom the girl previously disdained, falls ill once more, this time fatally. Now aged 19, the girl returns home. She becomes a devoted caregiver. But her self-destructive impulses cannot be quieted. Nor is she able to make peace with her raging, grieving mother.

I was reminded of Charlotte Roche’s 2013 novel, Wrecked, an equally disquieting and conventionally linear work. Despite the differences in prose style, the novels share certain similarities.

Neither woman has much time for smoothing life’s sheet corners. Each is drawing on autobiography: Roche’s three brothers were killed en route to her wedding, a horror she heaped upon Wrecked’s protagonist, Liz, while A Girl Is a Half-Formed Thing is dedicated to Eimear McBride’s brother, Donagh, who died of a brain tumor, exactly as the brother in the novel did.

However, a critical distinction must be drawn; where Charlotte Roche aims for shock and disgust in her writing, Eimear McBride’s intent is literary. Challenging and painful, A Girl Is a Half-Formed Thing’s sharp prose feels like a thicket: readers must bash their way in. Once there, one is inside the head of a tormented young woman. It is not a pleasant place to spend time.

I struggled with A Girl Is a Half-Formed Thing. I didn’t like it and feel heretical admitting so. The promotional literature folded into my advanced reader’s copy glowed far brighter than usual: I held in my hands the fall novel, certain to shatter, stun, shock, all the while racking up more awards.

Normally, these assertions are easy to ignore, but no less than Elizabeth McCracken and Anne Enright raved about A Girl Is a Half-Formed Thing, with Enright calling McBride “a genius”. This gave me pause. When writers of this caliber praise a novelist so highly, and when that novelist wins a major prize, well, something is out of joint. Or someone.

I’m not urging readers to share my feelings about A Girl Is a Half-Formed Thing – just the opposite. Others may find the novel less distressing. I found A Girl Is a Half-Formed Thing to be the literary equivalent of a shot of the blackest espresso: sharp, jolting, and acidic. This isn’t necessarily bad; I’ll take it over a romance novel any day. My admiration and respect for Eimear McBride is boundless. But I struggled to get through this book.

I’ve yet to see comparisons to James Joyce, but they’re surely coming—for the misery peculiar to the Irish, for the way religion permeates life without offering solace, for trenchant alcoholism, the incest, and the way sex becomes a vehicle for violence. Certainly, the writing is pruned to a nearly primal level of expression. Eimear McBride is said to be writing a second novel. It is hard to imagine what will follow A Girl Is a Half-Formed Thing.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)