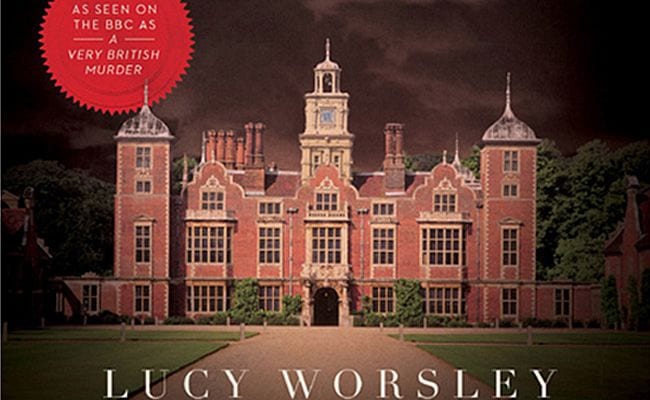

It may just be the timing of Lucy Worsley’s The Art of the English Murder that left me a bit indifferent. Based upon the BBC television series A Very British Murder, which I have not seen, perhaps the book better serves as a companion to that program than as a standalone work of cultural history or literary criticism. Then again, my lukewarm response may be altogether unrelated to the book itself. I mean, when beheadings and crucifixions are daily news, and the video footage just a mouse-click away, Stephen King starts to look less like the master of horror and more like a neo-realist, and murder mysteries risk coming off as bowdlerized accounts of the police blotter in your local newspaper.

Ironically, I think Worsley would understand my ambivalent feelings, both about her book and about the murder genre as a whole. After all, murder really only thrives as entertainment, she tells us, in times of relative security. “Its development went hand in hand with ‘civilization’, gas-lighting, industrialization, life in the city: everything that allowed people to feel safe from nature and its dangers.” The second half of the 19th century saw the murder rate drop, for instance, precisely when “the activity of enjoying a murder became increasingly acceptable.”

We might be tempted to dismiss the fascination with murder as symptomatic of the human propensity for cruelty and sadism when we read in Worsley’s book that at one time hundreds of spectators would line up to walk past the crime scene and gawk at the victims of a murder, as they did on the occasion of the Ratcliff Highway Murders in 1811. Yet, “there were two good reasons why this ghoulish practice was much more acceptable then than now. Firstly, both birth and death were much more part of normal domestic life.” And secondly, justice “…was still a matter for the community, not for professionals. It was important that any available data could be seen and shared by as many people as possible.” Law enforcement and investigation as we know it was in its nascent stage, and dependent upon the public for clues. That said, Worsley admits that many of those visiting the site of the murders “must have also been motivated by a third factor: morbid, salacious curiosity.”

As a reader, at times I also felt driven by a certain abject allure as I turned the pages. Worsley’s book is replete with photographs — not of crime scenes, thankfully — but of the protagonists of these crimes and their mementos, along with objects such as book covers that have become their legacy. Worsley clearly knows this feeling, too. While filming the television series, she was able to see and to touch many of the artifacts she discusses in the book, an experience that tests her ability to come up with oxymorons able to convey her feelings. We are told she was “ghoulishly pleased” to tinker with Thomas De Quincy’s opium scale; and that it was “gruesomely thrilling” to touch a condemned killer’s preserved scalp. To be fair, however, most of these expressions are found in her brief introduction, and overall Worsley manages to limit the cheekiness and still maintain a conversational tone.

The Art of the English Murder is not academic in either the negative or positive sense of the word; there are an almost equal number of descriptive and informative passages. In the postscript she writes: “All through writing this book I’ve been worried about being too flippant about murder. It’s not all good clean fun. There is horror here, and tragedy, beneath the puppetry and pageantry. But among the gore and horror,” she adds, “we’ve also glanced aside at the history of literature, of education, of women’s place in society and of justice.”

Often these topics are given just a glance, but if the book were reduced to a working thesis, one that is supported periodically throughout, it might be this: that in 18th and 19th century England, the art and spectacle of murder was ultimately didactic. Whether recounted in the form of a murder ballad or puppet show, retold in an early broadside or in the form of a “Penny Blood”, the art of murder almost invariably condemns the villainous murderer and champions justice. What Worsley suggests of “Newgate Novels” appears to be true to some degree, for most of the murder entertainment of the period: “Almost inevitably, reality became embellished and, indeed, glamorized. In the timeless journalistic manner, the regurgitation of the gory details is justified on moral grounds by an editorial voice that condemns each fact even as it relishes it.”

For myriad reasons, that moral frame of reference will disappear towards the latter half of the 20th century, so that by the time Alfred Hitchcock is making his films, the concern is no longer “about good and evil, right or wrong. Instead, [Hitchcock] simply aimed to extract maximum fear, horror and humor from his audience.”

Subtract humor from the above equation and the same might be said to be the object of ISIS or of Al Qaeda, or, for those more cynically inclined, of many Western governments continuously on high alert. Perhaps not surprisingly, then, the last chapter of Worsley’s book is titled “The Decline of English Murder”, an allusion to George Orwell’s 1946 essay of the same title. Given our new millennial tensions, it will be interesting to see whether or not “the art of murder” can survive our contemporary climate of general anxiety and alarm.

As I write, the UK threat level is listed as “severe”. In the USA, it is “elevated”. Reminders abound that we are never truly safe. So, if the genre does survive, it may well be for the sake of nostalgia, and this would not necessarily be a bad thing.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)