The trope of the writer who lives a life of suffering and turns it into high art is a ubiquitous one, but usually it’s little more than a romantic fiction.

In the case of Ludmilla Petrushevskaya, it happens to be entirely true.

Born in Moscow in 1938, her early years were comprised of war, evacuations, hunger, and homelessness. She lived on the street, begged for food, and spent her youth in a sequence of those infamously dreary Soviet communal housing blocks. Chunks of that time were spent sleeping under a desk in her senile grandfather’s bedroom.

Her first husband died young after several years of paralyzing illness, leaving her to support herself, her mother and a young child. Not even the editors who risked their futures by publishing Solzhenitsyn would take a chance on publishing her work: stories depicting the tough daily lives of Russia’s women were apparently more dangerous than whatever political subversions circulated from the more prolific male dissidents. Many of whom fled the country, while Petrushevskaya stayed and struggled on.

Anyone who considers the bleak, dark tales she tells to be unrealistic might think twice after learning a bit about her background. Those who wonder what it must have been like to try to eke out an everyday existence under the steel fist of totalitarian poverty begin to feel something of what this would have been like from the fatalistically bleak stories Petrushevskaya has penned. The tragic irony, of course – also reflected in her stories — is that the suffering continues unabated, with rich gangsters replacing corrupt commissars. The villains change, but the noir lives of everyday women and families retain that bleak and fatalistic quality.

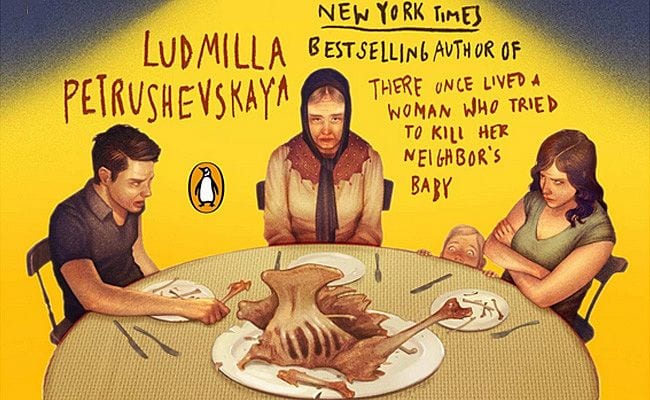

It’s a quality expressed in full measure in the latest compilation of Petrushevskaya’s stories to be collected and translated by Penguin Books. There Once Lived a Mother Who Loved Her Children, Until They Moved Back In: Three Novellas About Family is the third collection of her work Penguin has published, the previous of which have been received with acclaim (and bestseller status) by Anglophone and North American audiences. Her translator, Anna Summers, contributes a useful essay to introduce and contextualize Petrushevskaya’s work, and she acknowledges how important is the fact that someone has managed to produce such a searingly accurate chronicle of the suffering of Russia’s women: “All that immense quantity of suffering and squalor would be lost, would disappear into a historical void, if it hadn’t found a laureate in her. Suffering is bad enough, but permanent invisibility is even worse.”

The thing about Petrushevskaya’s work is that her stories have such a well-portrayed depth of bleak suffering and fatalistic irony that they are irresistible and one cannot put them down, however villainous and scheming the characters and however overpowering the drama. The reader even finds themselves laughing aloud at Petrushevskaya’s matter-of-fact way of relating the sordid and twisted tales, which seem both convincing and impossible all at once. It’s little wonder she received her first widespread acclaim as a playwright, and as one who depicted real and honest everyday characters. Russia’s women are the real storytellers, she once told an interviewer; she was just a good listener.

The characters in these stories are convincing even while they are fantastical, because they resonate with the potential darkness every reader knows lies buried within their own souls. Poverty and suffering bring out such qualities, and the result is a suite of characters who must deal with material deprivation, political repression, and the survivalistic scheming all this induces. The stories are realistic enough, but it’s as though one went through life with the worst possible things always happening. If for some people the glass is half full, for Petrushevskaya’s characters the glass is not only half empty, but what remains is leaking out through a shard that falls on the ground and pierces the carotid artery of one’s cousin, resulting in murder charges against the poor soul left holding the glass.

The new collection contains three longer stories, verging on novellas. There are two early period ones: The Time Is Night (from 1992) tells the story of a suffering woman poet who dies unrecognized; Among Friends (from 1988) is a delightfully caustic and scandalous tale about the weekly salon-style parties of a group of Russia’s suppressed intelligentsia over the course of several years. The final story, Chocolates With Liqueur, dates from 2002 and is a modern Russian re-telling of Edgar Allan Poe’s The Cask of Amontillado, told Petrushevskaya-style (the two would probably have gotten along famously).

Like all of her work, these are not cheery stories, but they possess a certain charm. They’re also very real, again in the sense that if you chose to see everything that happened around you in a negative light, this is what you would see. The characters are selfish, grasping, and scheming. Children are ungrateful toward their parents; neighbours scheme and gossip; men are always materially and sexually exploitative and women are always jealous and repeat their mistakes in life and love as often as humanly possible.

Petrushevskaya has an unparalleled talent for portraying the dark side of humanity; never in a malicious or didactic style, but with an almost eerily perceptive precision. Yet the tales are compelling, and told with such a fatalistic honesty that a wry and sardonic sense of humour at the merciless cruelty of fate emerges. Although dark and depressing, they are also endlessly entertaining. The types of themes and characters recur consistently in her work, but they don’t grow old or tiresome. Each new telling of the same old tale retains enough spark to amuse the reader, no matter how or how often it’s told.

Thankfully, Petrushevskaya’s work has finally achieved the broader and global recognition it deserves. She first made her name writing plays, but also worked in radio, television and magazine journalism. It wasn’t until the collapse of the Soviet Union, when she was in her 50s, that her prose began to legally circulate, but her prolific writing has now achieved wide acclaim. She’s also a visual artist, and even started a late career (in her 60s!) as a cabaret singer.

One can certainly say that Ludmilla Petrushevskaya has taken from life as much as it has taken from her. Happily, she’s also given a great deal back to all of us.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)