In the original Star Trek episode “City on the Edge of Forever”, a time machine shows the intrepid crew of the U.S.S. Enterprise history flowing through its portal. Step through and a person is instantly transported to the time being displayed. Time is pierced at an exact moment. W. Joseph Campbell punctured history with his keyboard through the world’s own temporal stream when he typed 1995: The Year the Future Began, an exploration of key events that one would think would form the basis of our contemporary reality.

Campbell’s assertion that 1995 was the first stop along the future is more than a bit presumptuous. That the Internet’s first “person” view of history begins around 1995 only proves the point that the Internet, as a repository of history, started collecting its data around that year. Different perspectives, however, would yield different dates. It’s interesting, for example, that the first chapter titled, “The Year of the Internet”, posits that modern history began with the World Wide Web. The World Wide Web, or WWW, is a technology derived from work at the European physics lab CERN, the very CERN so prominent now as the discovery point for the Higgs Boson. Ask a physicist at CERN when history began and he or she might well say 1913, the year that Niels Bohr first asserted the structure of atoms and the quantum behavior of electrons as they move between energy states.

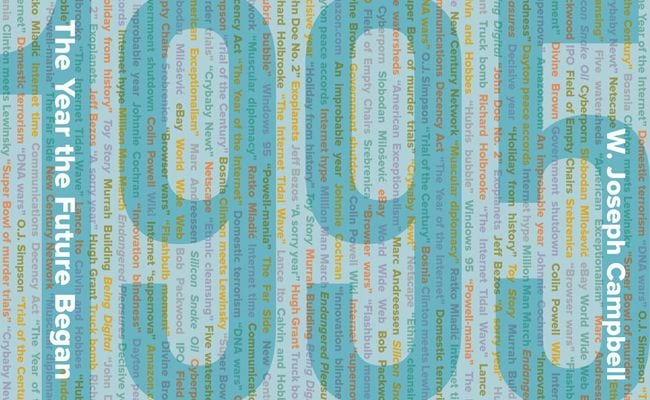

History is, of course, vast and continuous, multidimensional and heavily interwoven, and full of places whereon one might start “a history”. Campbell has the right then to choose 1995, the year the Netscape and Internet Explorer wars began, the year that Amazon started it’s online book store, the year of the Oklahoma City bombing, when the world watched the O.J. Simpson trial, the year of Bosnian peace talks in Dayton, Ohio, and of course, the year Bill Clinton met Monica Lewinsky.

The 1995 date, while accurate to the material, is relative to actual history. Campbell often rounds up or down to the ’90s, rather than remaining precisely fixed to 1995. He can be forgiven his temporal incursions. Editors, after all, tend to favor declarative statements for book titles. Thomas Friedman did not write, The World is Flat under Certain Circumstances, but rather, The World Is Flat; Brent Schlender and Rick Tetzeli wrote Becoming Steve Jobs, not This is How the Steve Jobs Persona Developed, We Think, After Interviewing a Bunch of People Who Knew. So readers of 1995 must take its assertion as a container for ideas— a book about events that circles a focal point — though the major events in 1995 all take place in that year, their origins and implications fall well outside of it.

That the events detailed in 1995 became important to history, then, are a matter of reflection and opinion. There seems, however, to be a general unwillingness to expound on implications in more than a passing way. While 1995 presents its subjects with great detail and scholarship as demonstrated by the copious notes that weigh in at nearly half the title’s volume, Campbell creates a book that is scarce in contemporary relevance.

The meeting of Clinton and Lewinsky, for example, ends up in impeachment hearings that presage the current animosity of the Left/Right divide that dominates the US political landscape. Impeachment, however was three-years away from 1995. More important than the Lewinsky scandal was the brief government shutdown that arguably facilitated her meeting with President Clinton; or at least gave the President time to consider a liaison with his intern. This was the first of two government shutdowns, the second spilling over to January of 1996. The events leading to the impeachment of a U.S. President and the shutdown of the Federal government are certainly two significant historical events, but the chapter on Clinton and Lewinsky doesn’t end with revelations about how their tryst transformed political reporting from at least a purported sense of propriety and objectivity into something more tabloid.

No, the chapter ends with the demise of Bob Packwood, the Oregon Republican who ended his 27-years of representing his state after a three-year investigation into sexual misconduct—an investigation filled with intrigue, evidence tampering and abuse of power. The final paragraphs tell not of the implications of all of these sordid scandals and the political infighting that surrounded them, but of the transformation of Packwood into an effective lobbyist. Is the point here that America’s memory is short and contextual? As long as Bob Packwood isn’t in office, his offenses are no longer relevant. Is the point, then, that as long as the economy is booming, we can forgive a sitting President a few minor transgressions? I don’t know. 1995 never digs in with meaningful analysis.

Campbell’s writing on the Oklahoma City bombing typifies 1995’s lack of critical insight. While domestic terrorism still occurs, the United States has become much more focused on external motivations rather than internal ones. While school shootings still cause us to tremble, most of those stem from more local, personal issues. Why is the Oklahoma City bombing a central event in our current history? Domestic terror, I would argue, is today more the lone wolf terrorist striking out on behalf of some external ideology rather than from pure domestic disenchantment.

While a connection may exist between the internal self-hatred that motivated Oklahoma City and the current rash of externally motivated terror attacks, Campbell doesn’t take us there. Campbell’s conclusion to the Oklahoma City chapter wonders, strangely, why the memorial in Oklahoma City fails to memorialize the perpetrators of the crime. For this reader, the story of Oklahoma City is about the lost lives, not the misguided ones. Any memory of terrorism should focus on extinguishing the opportunity for people, any people, to perpetrate their crimes on others. That we prevent future loss of life is a contemporary moral that can be drawn from the Oklahoma City tragedy. McVeigh himself deserves to be lost to history.

Is their value in 1995? The book clearly represents a well-researched trip down memory lane. While it may not support its central assertion, the tales it does tell are better than most aired in a television documentary. Campbell makes no attempt to argue that any other year would make just as worthy an examination, nor does he elevate individual events to provide a holistic sense of 1995. Other books that selected years to examine do a much better job of either tying their connections to historical implications, such as 1215: The Year of the Magna Carta or creating a more inclusive sense of contemporary atmosphere, such as that found in 1939, The Lost World of the Fair or A Year in the Life of William Shakespeare: 1599.

Campbell argues in his conclusion that 20 years is enough time to gain some perspective on what happened. It seems that 20 years provided ample time to collect all the facts, but for those of us who lived through 1995, perspective and meaning may require more attention—and attention, in a world dominated by the ephemera of the Internet that first entrenched itself in 1995, seems like a resource ever more difficult to muster.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)