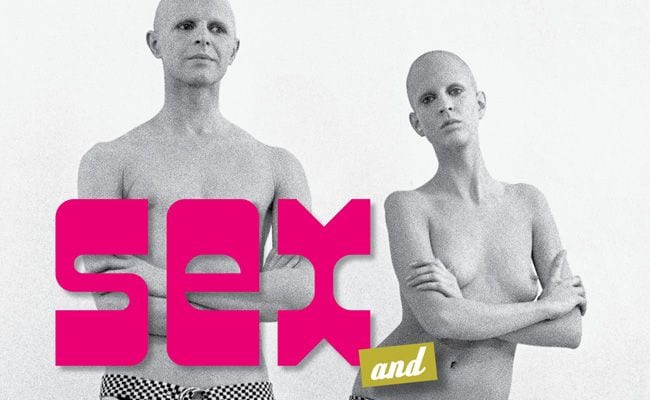

Jo B. Paoletti’s new study Sex and Unisex: Fashion, Feminism and the Sexual Revolution confirms what many readers will have long suspected: society has made a big convoluted muddle out of gender, sexuality, and fashion.

The author of Pink and Blue: Telling the Boys From the Girls in America expands her previous work on the cultural gendering of children’s fashion to explore how cultural notions of gender and fashion have intersected for adults – as well as children – in 20th century America, particularly in the aftermath of the post-WWII ‘sexual revolution’.

What do terms such as gender, masculinity, femininity, or unisex even mean in today’s world? Scientifically speaking, perhaps they no longer mean anything, and that may be the eventual resolution of the ‘sexual revolution’. In fact, Paoletti suggests it may turn out to be more like a hundred years’ war than a revolutionary moment in time.

Although the book’s title highlights the unisex fashion movement of the ‘70s, what it offers is a chronological analysis of gendered fashion trends throughout the second half of the 20th century. The picture that emerges demonstrates the complex ways in which fashion and the changing cultural politics of gender were used to both reinforce as well as challenge prevailing norms of social behaviour. This longer historical perspective reveals the inconsistency behind socially constructed notions of ‘masculinity’, ‘femininity’, and even ‘sex’ and ‘gender’. In popular culture, with each generation invariably unable to look beyond its own experience, the long-term trajectory of these concepts – and the fashion trends they engaged with — tends to become obscured. Paoletti’s research helps bring a broader perspective to the picture, and it becomes evident that conflicts over fashion invariably mirror efforts to challenge and transcend each generation’s restrictive social and behavioural norms.

It’s thus possible, for instance, to understand the apparent contradictions within feminism’s relationship with fashion as emerging from the complex and individually differentiated experiences of gender. “Women’s rights movements have been, at least in part, a rebellion against the cultural construction of femininity”, writes Paoletti. Which explains why – depending how culture constructed femininity(s) – fashion trends could either impose oppression or offer liberation. And often both at once.

Complicating these matters is the intervention of psychology. As Paoletti explains, prior to Freud there was a loose expectation that gender was innate and would emerge on its own; indeed, that it could be damaging to push children into gender roles before they were ready (hence the 19th century ambivalence with boys wearing frilly dresses and nightgowns into a sometimes advanced age). It was when Freud and his successors came along that notions of gender as culturally constructed threw a complicated monkey wrench into child rearing. “If gender could be taught that still begged the question of which gender rules should be passed along to the young,” Paoletti observes. On the one hand, acknowledging the power of nurture over nature demonstrated the arbitrariness of gendering behaviour and had a deeply liberatory potential. At the same time, it created a heightened pressure to ensure children conformed to what were considered socially acceptable gender roles, much of this driven by the era’s societal fear of homosexuality.

Moreover, scientific debates on the topic were often seized upon by ‘pop psychologists’ who turned disputed ideas into bestselling books that were adopted as parenting and schooling trends, regardless of their credibility. “Part of the problem is that when the science of psychology is translated into pop psychology, it is out of the scientists’ hands, subject to the whim of cultural expectations. There’s no way for the experts to steer it as it works its way through our culture and back into our attitudes and behaviour. There’s no peer review, no public discourse. The concepts, images, and discarded truths take on a life of their own and are passed on from one person to another as common knowledge or urban legend. Yesterday’s ‘discoveries’ live on, infecting new minds and seemingly immune to correction or retraction.”

Of course, scientists aren’t off the hook either, as Paoletti discusses: the notorious brutalization of intersex children by then-acclaimed and now-infamous psychiatrist John Money (who sought to impose gender identities on them; a practice that still exists) reflects the very real damage scientific trends can inflict before they too are discredited and discarded.

At the same time, shifting and fluid scientific theories of sex and gender were being taken up to serve rigid political agendas, particularly in support or opposition to feminism. “Useful as the concept of gender as separable from sex is, it introduced a messy new variable into popular notions about sex and sexuality… For many conservatives and antifeminists, biological essentialism (biology is destiny) was replaced by cultural chauvinism: yes, gender roles are cultural, but the traditional (Western, Judeo-Christian, middle-class – take your pick) cultural norms are superior and should be preserved.”

Charting Change Through Fashion

None of this history of shifting cultural understandings of gender is new; but what is interesting is charting the trajectory of these trends through fashion. Paoletti draws on a wide range of sources, analyzing Sears catalogues, sewing patterns, the evolution of designer fashion labels and the relationship between fashion and pop culture, notably pop music. She explores ‘The Peacock Revolution’ of colourful fashion among men in the ‘70s, and of course that eventual unisex moment. Unisex, Paoletti notes, did not mean sex-less: “Fashion is about sex and sexuality as much as it is about gender.” Unisex fashion in fact often accentuated sexuality while conveying a message that sexuality did not need to be confined to traditional modes of expression. “Ironically, unisex fashions for adults did not really blur the differences between men and women, but instead highlighted them.”

All of this led to mixed results, reports Paoletti. Scholars note that “the sexual revolution produced a culture that was more comfortable and open about sex, which led to greater comfort with homosexuality and androgyny.” However, it wasn’t a steady trajectory: the comfort of the ‘70s with androgyny and the trendiness of bisexuality (masking a growing cultural comfort with homosexuality) led to a counter-reaction in the ‘80s, during which distinctly ‘masculine’ and ‘feminine’ clothing styles were revived with a vengeance, and even imposed on infants (as evidenced by the blue-for-boys, pink-for-girls associations that were powerfully imposed during this period). “Unisex and androgynous clothing, far from being proof of more relaxed attitudes toward gender and sexuality, now appear to have been just the opening salvos in our own cultural Hundred Years’ War.”

Paoletti’s previous 2012 study Pink and Blue explores the broader social development of gender roles among children from a historical perspective, and she draws from this work to highlight the messy mix of concepts that society conflates and confuses when it talks about ‘gender’. From overly simplistic ‘nature vs. nurture’ debates to unhelpful linkages between gender and sexuality, she notes that there remains “a stubborn cultural insistence on reducing complexity to binary choices (nature or nurture, male or female, masculine or feminine), which encourages even more stereotyped thinking. All men are not aggressive, all women are not passive; most gay men are not effeminate, and vice versa. Within the categories we have constructed there is huge variety, which binary, stereotyped thinking ignores.” Historically, this has manifested in differing responses to behaviour that pushes the binary. Consider the differing reactions to ‘tomboy’ girls and ‘sissy’ boys (the latter, says Paoletti, tended to provoke more intense interventions, from bullying to psychological treatment).

One positive off-shoot of these complicated and messy debates, however, was a gradual acceptance of complexity instead of restrictive binaries (an acceptance often facilitated by commercial motive). In the late ‘70s, for instance, manufacturers realized girls’ stretch pants and tops were increasingly being purchased by parents for young boys. This led some manufacturers to introduce ‘boys’ lines’ for the items, which in turn became popular among girls. Cases like these demonstrate the ongoing race between manufacturers to reflect back desired social trends in binary and commercial form at the same time as customers were seeking to stay ahead of the curve by pushing boundaries and bending binaries, either intentionally or simply for reasons of comfort and personal expression.

Perhaps the most fascinating chapter is Paoletti’s study of court cases pertaining to gendered fashion. While there were occasional legal cases involving the right of women or girls to wear trousers, it was predominantly the push for acceptance of long hair among men that was the cultural fault line during this period. Between 1965 and 1978, she’s documented 78 cases at the state level or higher involving men fighting for the right to long hair (sometimes with a great deal at stake: negative outcomes included expulsion from school, dismissal from jobs, even fines and imprisonment). During the early ‘60s these often involved challenges to school dress codes, but in the ‘70s the challenges expanded to the workplace. Interestingly, the outcomes were different, Paoletti observes. While there was a more or less even split in legal outcomes at the school level, courts were more prone to enforce employers’ rights to impose hair and dress codes. Still, there were some successes, particularly in light of civil rights and Equal Employment Opportunity legislation. The issue became further muddied by a growing Black Power movement; in addition to cases involving long hair cases involving afros entered the mix.

Paoletti observes that Title IX – the American legislation that ensures equality in federally funded educational activities – is most often remembered for boosting access for women and girls in sports. Yet it also played an important role in fashion cases; lawyers used it successfully to defend boys’ rights to long hair, arguing that short hair requirements treated them differently from girls. In other cases, attorneys for long-haired boys argued that hairstyle was a form of protected speech under the First Amendment of the US Constitution (other cases variously cited the Third, Fourth, Fifth, Sixth, Eighth, Ninth, Tenth and Fourteenth Amendments). The strategies used to defend Americans’ rights to personal style were innovative and creative, and the outcomes a mixed bag.

Paoletti observes two broad trends in these legal struggles over style and fashion. First, dress codes imposed on girls were typically grounded in the notion of ‘modesty’ (a pattern replicated in today’s intensifying battleground over school dress codes that disproportionately target young women along the same principle). (“School dress codes ‘demeaning’ to both sexes” by Aleksandra Sagan, CBC News 14 May 2015) Those for boys, on the other hand, emphasized the need for conformity to authority and conventional standards; Paoletti suggests this reveals the fundamental “importance of conformity and submission to authority in postwar masculinity”. Enforcement of dress codes might have been justified by teachers and principals on the grounds of health, safety, and avoiding distractions, “but the disparity in the number of legal cases and the severity of the punishments suggest that the real underlying issue was resistance to authority.”

The other trend she notes is that battles over fashion, style and dress codes don’t break down so easily along generational lines, despite their often being attributed to a ‘generation gap’. In fact, sometimes it was older school board officials who defended the expressive rights of students to the outrage of younger parents, and of younger teachers. Likewise, violence and harassment against those who crossed boundaries was often inflicted by school-age peers (recall US Republican presidential hopeful Mitt Romney’s disturbing college-age gang assaults on long-haired boys). (“Mitt Romney’s prep school classmates recall pranks, but also troubling incidents“, by Jason Horowitz, The Washington Post, 11 May 2015) Indeed, the ongoing nature of these ‘culture wars’ demonstrates that the underlying issues transcend age or generation; otherwise those who challenged social conventions “would have won simply by outliving the opposition.” But no such easy solution has presented itself.

In seeking to understand the back-and-forth nature of fashion trends – moves away from clothing that entrench gender stereotypes back toward rigidly gendered fashions – Paoletti returns repeatedly to the notion of ‘punctuated equilibrium’, which “posits an evolutionary process of periods of dramatic change followed by periods of recovery”. In evolutionary biology, it suggests that “like a rubber band that is stretched too far, a species can either snap (extinction) or retreat to something like its original size and shape, just slightly altered.” Perhaps a similar process occurs with fashion – and, by extension, with cultural notions of gender. The growing together of men’s and women’s fashions into colourful, androgynous clothing in the ‘70s snapped back into the more rigidly defined and gendered fashions of the ‘80s.

There’s a compelling logic to the notion. But even more compelling is her notion that the sexual revolution unleashed not a moment of change but decades of it: “we are still untangling the complicated relationships between sex, gender, and sexuality… but we are still years, if not decades, from resolving all of the issues raised by the sexual revolution.”

Perhaps the final victim of that revolution will be the idea of gender itself. Notions of masculinity and femininity cease to have meaning when we realize how interdependent they are: something is masculine because it’s not feminine, and vice versa. “The binary model of sex, particularly the notion of male and female as opposites, needs to join the flat earth and the geocentric universe in the discarded theory bin. I feel a twinge of sympathy for demographers who will have to come up with new boxes on forms to accommodate evolving notions of gender, but they already have had some practice adjusting to changes in how we see race, so they will probably be fine.”

What are we then left with? Paoletti suggests two options: “no gender categories, or a finite (but yet undetermined) set of gender categories.” And here, perhaps, scientific thinking – with its lingering obsession with rigid categories – can take a lesson from fashion. “If we desire a society of individuals, each empowered to achieve their full potential, we need to produce a culture that recognizes human diversity, offers options, and respects choices.”

There’s a lot to agree with, and a lot to disagree with in Paoletti’s book, but it’s an ambitious, creative, and thought-provoking study that offers much to consider. And it even ends on a hopeful note. For today, when parents discover that their children don’t fit into society’s categories of acceptable behaviour and identity, “increasingly their response is not to ‘fix’ their children, through training, punishment, or therapy, but to argue for cultural change.”

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)