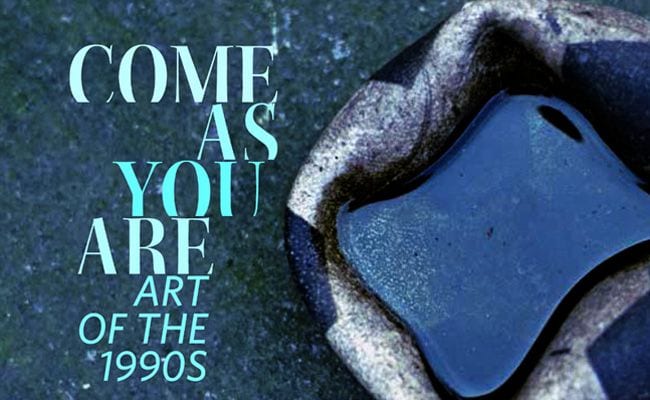

Come As You Are, a compilation of the Montclair Art Museum’s exhibit, Come as You Are: Art of the 1990s, showcases 65 works by 45 artists. It’s intent is to remind us of the electric feelings of Nirvana’s punk-derived chords, or maybe the first three lines…

Come as you are, as you were

As I want you to be

As a friend, as a friend,

…but it forgets the fourth line: “As an old enemy”. The curating choices here don’t pay attention to who the enemies might be, but rather, pays attention to relational networks, playing with problems with earnestness and the authentic. Like the band moves around the world, but unlike Cobain’s life does not end in abject terror.

The complexity of identity, audience, and capital is a strong current running throughout this beautiful book. I was born in 1981. Remembering Nirvana is but one nostalgic act of mid-’90s remembering, but there were others, of course (and this is the season for remembering the ’90s, with the release of the documentary film Montage of Heck and Lynn Crosbie’s literary fanfic Where Did You Sleep Last Night). This catalog is a handsome act of memory with a number of excellent essays, and it’s filled with first-rate images.

However, it remains a souvenir rather than a critique. The problem with the ’90s resting somewhere between spectacle and nostalgia, between excess and the abject, are all over this catalog. The decade was deadlocked into memorial nostalgia before it even ended, with shows in Los Angeles as early as 1994 functioning as a kind of archival memory project. The act of looking through the catalog is a complicated measure of memory, and returning to a political and social preview, this failed balance keeps one at a distance.

Part of this estrangement is how clean the idea of the ’90s is compared to how it exists in the audience’s unstable memories. Looking at the ubiquitous, much mocked “only ‘90s kids” meme, with its Disney sitcoms and nascent boybands, is different from my memory, which includes Spin magazine, PJ Harvey in Glastonbury, Riot Grrrl, and the abjectness of Mike Kelley on the cover of Sonic Youth albums.

Naming the book after a grunge song, but including work that is slick and conceptual, makes for an interesting conundrum. What were the ’90s like for the curators of Come As You Are? There are eight essays and an introduction: one on African American arts, one on the death of painting, another on America, one on net art, one on Los Angeles as an emerging arts center, and an essay on Gabriel Orozco, the only artist who has a singular essay.

Here are works that were mentioned in more than two of the essays: The 1994 Whitney Biennial, Thelma Golden’s 1995 show about black masculinity at The Studio Museum of Harlem (mentioned three times), Byron Kim’s conceptual paintings Synecdoche (mentioned four times, including a full-page illustration), Rosalind E. Krauss’ essay on grids from the mid-’70s, and Glenn Kaino’s sculpture, The Siege Perilous.

These works have a number of things in common: they mark an interest in the problems of diversity; they make an argument about the allowance of new forms, and; about access being expanded. They also talk about networks — how formal conversations about aesthetics have the potential to now be about social and cultural politics.

In the introduction the curator, Alexandra Schwartz, elucidates the ongoing problem of diversity as a problem of new networks:

…many of the artists associated with these discourses worked outside the United States, and the first exhibitions to engage with postcolonialism likewise took place abroad. However… a key point in of tension in this period’s history rests in the relationship between so called identity politics and multiculturalism in the United States, and postcolonialism and globalization internationally… (14).

Schwartz maintains an interest in a kind of checklist diversity (diversity is a matter of the right demographic mixture, thinking of Clinton’s triangulation might be another ’90s example). If the ’90s were about the opening up of diverse discourses, then this work is commendable. However, some of the resulting conversation is shallow, and most denies a kind of new internationalism that marked much of ’90s at the moment when the art fair begins to triumph, and when new biennials bloom like a thousand post-capital flowers. This might be the central problem of the ‘90s — how to talk convincingly about the problems of selling out when you do stadium tours and are funded by corporate interests, for example.

Discussing international representation first, the catalog includes: Julie Mehretu, born in Addis Ababa; Prema Murthy, who was educated in London; Mariko Mori who is Japanese, and the Mexican Gabriel Orozco. Each of these artists produce works about networks, sometimes about the digital, sometimes about patterns that move in larger circles. Even the problem of local scenes was about the collapsing of Diasporas and the expanding of networks.

For example, the emerging Cal Arts scene was in many ways about the Pacific Rim expanding as a trade zone post-’80s, or the scene that surrounds new black aesthetics crystallized by the Venice Biennale in 1993 — one of the works in that Biennale were museum tags that spelled out the maxim, “I don’t even want to be white.” One of the most powerful things about art in the ’90s was that not imagining wanting to be white meant that there were so many other imaginings that could occur. This was seen, for example, in the 1994 Studio Museum of Harlem Show, Golden’s Black Male, whose primary goal was to bring the margins into the center, therefore reframing and recasting racist networks.

These networks include time-based work, and considering the problem of cohesively cataloging ’90s art, I’m thinking about the implications of a canon that is emerging. One of the most interesting things about these kind of survey shows is working through what was interesting then and what seems necessary now. The essays in Come As You Are don’t talk about reception. There are reproductions of Matthew Barney’s films, for example, but there are few mentions of the works themselves. His work seems more like the capital of the dotcom boom — inappropriate in a time of austerity. The repeated mention of The Siege Perilous — an Aeron Chair on a rotating plinth – may be a a much better symbol for those times.

Speaking of metaphors on the opposite end of Barney, the high femme, well-crafted narratives of Karen Kilimnik and Laura Owens are mentioned mostly in passing, mostly about their relationship to their work in LA. But Lisa Yuskavage isn’t mentioned at all, though John Currin is, and reproduced. Yuskavage’s work seems difficult and precedent setting in ways that John Currin’s seems dated (this may be my ongoing boredom with the straight male gaze). The book made me wonder where Nikki Lee went, after her series where she pretended to be Latino, Redneck, Goth, and other kinds of American subcultures; or where Mariko Mori went, after she decided that she wasn’t human.

Come As You Are is a solid work, though less explicit than I would like. Although it has a helpful mapping chronology (exhibitions mapped against world events) and a bibliography, it would benefit from an index and an active list of works cited. The categories and the intersections of the categories could be plotted. However, this book makes me reconsider how I think I viewed the ’90s at the time, and how I remember that era now — though Mike Kelley on the cover of Dirty is still my explicit token.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)