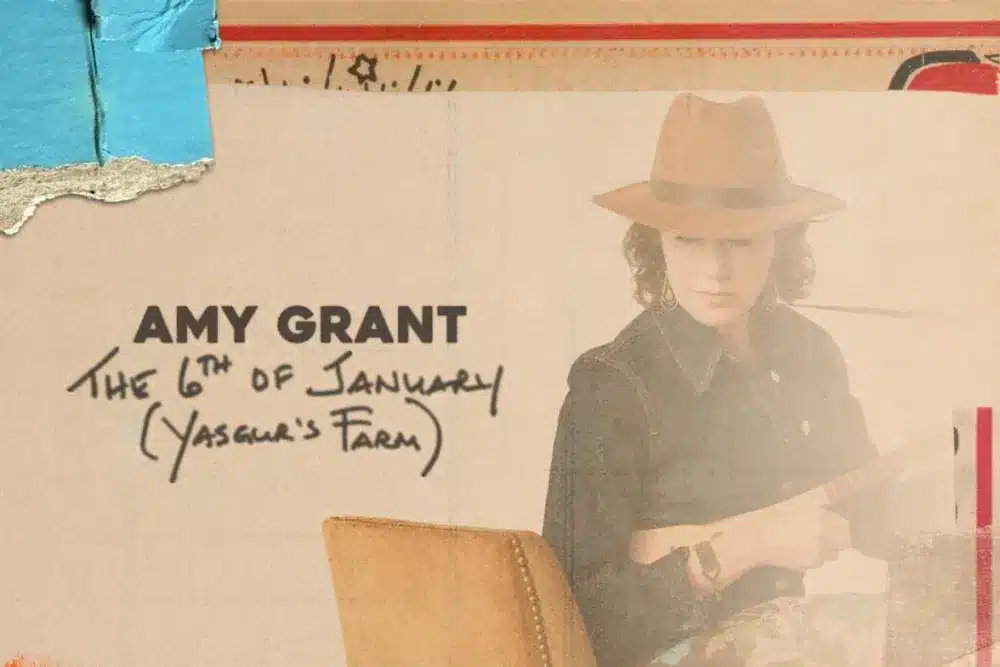

Maybe it’s that the music recalls classics by Suzanne Vega, Shawn Colvin, Lucinda Williams, et al. Perhaps it’s Mac McAnally’s pristine yet warm production, full of strummed guitars. Maybe it’s the ease of Amy Grant’s delivery, with her melodic variations serving as hooks. Perhaps it’s the verse about John Lennon. Amy Grant‘s “The 6th of January (Yasgur’s Farm)”, released on 6 January 2026, touched and captivated me, inspiring me to share it with anyone I thought would be receptive to its message.

I felt that need the way I think Grant felt the need to deliver the message. The song’s release date marked the fifth anniversary of the armed insurrection at the United States Capitol, the seat of the US Congress, in Washington, DC. In “The 6th of January”, Grant uses that event as a yardstick to measure how far the US (at least, unfortunately, it may extrapolate) has strayed from the ideals and idealism of the 1960s. “I look ahead and realize we’ve lost our way”, she sings.

Amy Grant’s name is at the top of the recording, and she’s the focus of the official video, but we should think of “The 6th of January” as a collaboration. The song was written by Sandy Emory Lawrence. The web doesn’t offer much information about this reclusive songwriter. In 2013, she won the ASCAP Sammy Cahn Award for her song “The Pretty One”. She once worked with the country and bluegrass duo Joey + Rory. She has released one CD, The Hammer Lands, under her own name.

Before becoming a songwriter, Lawrence envisioned a career as an academic poet. (This information and subsequent quotes from Lawrence come from her 2016 interview with Southern Exposure Magazine.) The lyrics to “The 6th of January” are poetic in the best sense: subtly dramatic, seemingly plain-spoken, yet rich with intricacies. They begin with an unidentified reference: “She says maybe it’s the time of year / Or maybe it’s the time of man.”

This abrupt opening suggests an autobiographical story already in progress. At first, especially before you learn that Lawrence wrote the song, you might think this “she” is a friend or relative of Grant’s.

At some point, you may realize that these lines contain lines from Joni Mitchell‘s 1969 song “Woodstock”. Lawrence includes Mitchell among her major influences. At age 15, she saw Mitchell performing on television, “pointed at the TV and said, ‘[T] hat’s me. That’s who I am’.”

Mitchell wrote her ode to the Woodstock music festival and its collective hippie spirit right after the event. The following year, the song was recorded three times: by Mitchell, by Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young, and by Matthews Southern Comfort. If “Maybe it’s the time of year / Maybe it’s the time of man” don’t register for you, maybe you know these lines, which aren’t in “The 6th of January”: “I’m going on down to Yasgur’s farm / I’m going to join in a rock ‘n’ roll band… By the time we got to Woodstock, / We were half a million strong.”

Journeys permeate “Woodstock” and “The 6th of January”. In the latter, the singer turns out to be listening to a “1960s playlist” and drinking “a beer”. Then “suddenly” she is “16 again” as she recalls the 1960s. Amy Grant was actually born in 1960 and, by age 16, was performing Christian pop music that made her famous; she released her first album in 1977. Still, she clearly identifies as a 1960s idealist. I was born in 1965, and at heart I’m a 1960s idealist. “I hope some day you’ll join us / And the world will live as one”, as John Lennon sings in his 1971 anthem “Imagine”.

In the official video for “The 6th of January”, a picture of Grant as a teenager appears at this point, then is joined by and replaced with her adult self. Together, both incarnations wonder about “the future”: “What’s it hiding up its sleeve?” The adult then wipes away any utopian illusions, seemingly shaking her head at the memory: “All that wide-eyed hope / Were we so naive.” A jump cut takes the singer to the Hudson Valley, in upstate New York, where she’s looking for the site of the music festival. “And we’ve got to get ourselves / Back to the garden”, lines from Mitchell’s “Woodstock”, aren’t mentioned but seem apt here.

Woodstock took place not in the town of Woodstock but in nearby Bethel, where the farmer Max Yasgur—a conservative—allowed his land to be used. “Hey mister”, the singer asks, “where’s the road to Yasgur’s farm”. This “road” is, as roads so often are in art, real and metaphorical.

We don’t know who the singer’s asking. He could be an area resident, the ghost of Max Yasgur, or a voice that has existed through the ages, like a variation on Coleridge’s Ancient Mariner. “He stares at me with pity and alarm / Says that crowd left here long ago / Scattered all to hell and Harper’s Ferry / On the 6th of January.”

Lawrence and Amy Grant expect you to know or to look up what happened at Harpers Ferry (no apostrophe), Virginia, in 1859. That incident involves John Brown, whose actions had intentions and consequences. It’s up to you to connect and contrast the historical information with your understanding of what major newsworthy event happened 162 years later, on “the 6th of January” in 2021. It was, you need to know, for this song to signify the insurrection at the Capitol.

Some people believe, or would have you believe, that patriotism motivated the insurrectionists. The mob stormed the Capitol; did millions of dollars of damage to it; and injured, sometimes gravely, the police officers who were there to protect the building and the government officials and employees working in it. Some of the police officers later committed suicide. The insurrectionists aimed to save then-President Donald Trump from losing an election that he falsely claimed and still claims was stolen.

Lawrence and Amy Grant lament these open wounds. Their song declares that democratic ideals, a sense of collective progress, died that day. Alternatively, those ideals might have died years later, on the day that Trump pardoned the insurrectionists, rewarding them for their fealty to him.

What, though, is the exact significance here of Harpers Ferry? And of the crowd being “scattered all to hell”? The song asks you to work with the information you’ve gathered from the song and elsewhere. Each word in the lyrics carries significant weight, but no word completes the picture.

The next verse finds the singer in a grocery store. Over the sound system, she hears an instrumental Muzak version of Lennon’s “Imagine”. The “6th of January” video reverentially shows Lennon singing “Imagine” in a 1971 clip.

With the song’s utopian lyrics in her head, the singer, “fight[ing] a cart with crooked wheels” (symbolism!), wonders what Lennon would make of the situation. Forty-six years after his assassination, “[h]e’s either bent over laughing / Or spinning in his Strawberry Fields.” At this reference to Lennon’s transcendent 1967 Beatles song “Strawberry Fields Forever”, an exploration of consciousness, the video shows the “Imagine” mosaic in Strawberry Fields, the Lennon memorial in New York City’s Central Park.

What are Lawrence’s nicely observed lines saying? Is Lennon reacting to the absurdity of his song being emptied of meaning and being used in a purely consumerist context? In “How Do You Sleep?”, a song on his Imagine album, Lennon jabbed at his former songwriting partner, Paul McCartney, with lines such as “The sound you make is Muzak to my ears.” Lawrence, who cites Lennon and McCartney as two of her major influences, surely knows this line, a dismissal that makes the conversion of “Imagine” into Muzak all the more painful.

There’s another, larger interpretation of Lennon’s posthumous responses. The chorus of “The 6th of January” has already announced the dispersal of the Woodstock “crowd” and thus the utopian dreams of the 1960s counterculture. Lennon played a major role in those utopian dreams. In the singer’s imagining, then, Lennon might be commenting on the state of the US.

Lennon emigrated from England to New York City in 1971, and he fought very hard to become an American citizen in the mid-1970s, when the government tried to deport him. Many of us wonder what Lennon, if he’d lived into the 21st century, would have made of the US, the global rise of authoritarianism, global warming, and so on, imagining his humorous, furious, and/or despairing responses.

When Amy Grant then returns to the chorus—”He stares at me with pity and alarm”—for a moment, “he” may still be Lennon. Why would Lennon be answering her question about Yasgur’s farm? In our minds, Lennon’s image then transforms into the singer’s original interlocutor: an unidentified man, Yasgur’s ghost, a timeless voice.

Lawrence’s next songwriting trick is to get self-reflexive. On a car radio, the singer hears Marvin Gaye‘s “What’s Going On” from 1971. Gaye, like Lennon, made music through the 1960s, so the shout-out recalls that earlier “1960s playlist”. At the same time, this reference places “The 6th of January” within the context of topical—indeed, sociopolitical—songwriting. “Picket lines and picket signs”, Gaye sings in “What’s Going On”. “Don’t punish me with brutality.” (Alas, some things never change.)

“What’s Going On” unites the singer’s car ride with issues of Blackness. Blackness was running beneath the surface of the song, as you know or will learn from the Harpers Ferry reference, but now that topic becomes explicit. “Is it right on red or left on MLK?” Grant sings.

The combination of “right” and “left”, the association of “right” with “red” and “left” with “MLK”, the details of wayfinding and the subsequent declaration that “we’ve lost our way” offer significant wordplay. In addition, as happens a few times in this song, the specifics become generalized. For example, the thoroughfare “MLK” stands in for civil rights. You know that, or you will look up the initials, Lawrence and Grant hope.

Unmentioned in these lyrics or among Lawrence’s inspirations is the towering figure of 1960s topical songwriting: Bob Dylan. Often referred to as a poet and, of course, the winner of a Nobel Prize in Literature, that master of metaphor was on my mind in the days before I first heard “The 6th of January”. On my home stereo, I’d been listening to CDs of Dylan’s Christian music from the 1980s. Although I’m not a Christian, I can appreciate the power and beauty of Christian music by Dylan, Mahalia Jackson, Aretha Franklin, Charlie Rich, et al. (It’s called tolerance, people. It involves open-mindedness. You dig?)

Amy Grant remains best known for her Christian music, although she has enjoyed much crossover success. To the best of my knowledge, I’d never heard an Amy Grant song, and I didn’t know she recorded secular music. Presumably, the algorithmic overlords of YouTube knew nothing about my offline listening to Dylan when they recommended “The 6th of January”. Somehow, they knew I’d vibe with Grant’s music and message here.

Some conservative Christian commentators and Amy Grant watchers have denounced “The 6th of January”. They seem especially irked by the song’s use of “Imagine”. After all, the first thing Lennon and his co-writer, Yoko Ono, ask listeners to imagine is that “there’s no heaven… No hell below us / Above us only sky.” Whether Lawrence and Grant embrace every aspect of Lennon-Ono’s utopian vision is for them to say. Whether Christians “should” embrace or reject any aspect of “The 6th of January”, the believers and others will have to debate.

Lawrence and Grant no doubt want such debates to happen. They want dialogues, reckonings, to come out of this song. “The 6th of January” burns, the way the Ramones‘ 1985 “Bonzo Goes to Bitburg” burned in denouncing then-U.S. President Ronald Reagan’s visit to a Nazi cemetery (“my brain is hanging upside down”). However, “The 6th of January” delivers a slow burn, not a punk-rock anthem, nor a “Fuck Trump and His Supporters” bumper sticker.

This song both spells out its point and leaves gaps for you to fill. In assuming that you know some things, will investigate others, and will draw your own conclusions, Lawrence and Amy Grant invite you to complete the song’s vision.

In this way, their song becomes your song too. It’s participatory, like a democratic republic.