There is a ghost haunting Annie Lennox‘s solo debut album, Diva. While the record sounds at once timeless and timely, there is a presence from the 1960s (1969, to be exact). Diva’s sound is all high-tech gloss and early 1990s polish, and echoes of Dusty Springfield‘s classic Dusty in Memphis reverberate throughout it. Annie Lennox—one half of 1980s synthpop duo Eurythmics—is arguably the truest successor to Springfield’s title as the Queen of blue-eyed soul (though some would grant that honorific to Adele).

Likewise, Diva has endured for three decades as the seminal blue-eyed soul diva album. Lennox chose the title well because the LP has the pop diva camp and extravagant excesses that were dominant factors of Springfield’s appeal. When performing with Dave Stewart as the Eurythmics, she sported a hard, flinty androgynous image. Thus, there was a forbidden quality to 1980s Annie Lennox due to her orange buzz cut and boxy, shoulder-padded suits. But as a solo diva, she embraced the flamboyance of being a pop diva.

Annie Lennox had already racked up an impressive 16 years as a new wave icon when Diva arrived in April 1992. First, she was a member of the 1970s power-pop group the Tourists, and then she became a bona fide pop heroine and pop radio mainstay with Stewart as the Eurythmics. Their striking visuals made them giants of MTV, their videos in heavy rotation. Lennox’s powerful, soulful alto exploded through Stewart’s icy, neon-sluiced soundscapes. Songs like “Sweet Dreams (Are Made of This)”, “Here Comes the Rain Again”, and “There Must Be an Angel (Playing with My Heart)” became pop standards, scoring ’80s mainstream rock. Lennox established herself as a gifted singer-songwriter with a broad, muscular voice.

A self-avowed devotee of Dusty Springfield, Annie Lennox brought a genuine soul to her pop hits. Springfield, a significant student of Black American soul and pop, unearthed a stirring soul diva with her fifth album, 1969’s Dusty in Memphis. Working with legends like Jerry Wexler, Arif Mardin, and Tom Dowd—all of whom also worked with Aretha Franklin—Springfield traveled to Memphis and recorded much of the album in the hallowed American Sound Studio. The resultant record is now an American classic and the definitive blue-eyed soul album.

Springfield did not create the genre dubbed ‘blue-eyed soul’, nor was she a pioneer. Instead, she arguably became one of its most outstanding practitioners. In the 1960s, white pop and rock acts turned to Black music, swiping, stealing, and appropriating. The history of American popular music is rife with Black musicians having their work hijacked, the music blanched and made palatable for white audiences. There was a cynicism at play when teen heartthrobs would record soul tunes because they sapped away any spirit or soul.

But Springfield was a champion, not a dilettante, of the soul music that inspired her magnum opus. A devoted fan of Motown, she introduced Motor City’s biggest and brightest stars to British television audiences. In addition, reverence informed her approach to recording soul music. Lennox, a student of Springfield, looked to soul in the same way: as an earnest appreciator of the brilliant Black performers responsible for creating American pop music.

Like many ’80s British new wave artists, Black pop music heavily influenced her. To hear the depth of her appreciation of soul music, listen to Annie Lennox trade verses with music giant Aretha Franklin on the frantic dance-rock ditty “Sisters Are Doing It for Themselves”. The contrast between the two divas is fantastic, with Franklin’s churchy depth overlapping with Lennox’s glassy wail as both voices roar over Dave Stewart’s clattering, cluttery production.

The music on Diva has a somewhat leaner sound than the work Lennox recorded with Stewart. It feels like a natural evolution of the Eurythmics. Producer Stephen Lipson slathers the songs with as much studio gloss and sparkly production as Stewart did. At the same time, the songs have the trademark sound of early 1990s mainstream pop records: densely and heavily produced, with a lustrous sheen. Unlike the songwriting of the Eurythmics’ greatest hits, Lennox was responsible for the tunesmith on Diva, receiving sole writing credit on nine of the album’s 12 tracks. The compositions on Diva run the gamut from thumping dance numbers to weepy ballads, all informed by Lennox’s inimitable strident vocals.

From the record’s opening track—the moody, mesmerizing ballad “Why”—to the throbbing closer, “Step by Step”, Diva’s tracklist is a meticulous display of Lennox’s musical chops. She displays an eccentric flair for the slightly ridiculous, adding pulsating synths, jolly strings, and manic vocals to create a modern tribute and update to the classic soul-pop record.

The album’s first single, “Why”, was a great way to launch Annie Lennox’s second career after her success in the 1980s. It wasn’t the first single credited to Lennox as a solo artist, as 1988 saw her team up with another soul legend, Al Green, to cover the Jackie DeShannon classic “Put a Little Love in Your Heart”. Yet, that track was produced by Dave Stewart, whereas “Why” saw Lennox take a graceful step away from her association with her Eurythmics partner.

The slow song starts with a stately, humming synth and a twinkling piano before a choir of heavenly voices repeatedly ask, “Why?” This prelude prompts Lennox’s voice to make its entrance, the thick instrumentation seeming to part like a curtain on a stage. It’s a luxuriously sad song, a tear-jerker that sees Lennox exuding self-recrimination as she wonders, “How many times do I have to try to tell you / That I’m sorry for the things I’ve done?” She then bitterly notes, “I tell myself too many times / Why don’t you ever learn to keep your big mouth shut?” It’s Lennox’s take on the classic tragic soul ballad, much like Aretha’s “I Never Loved a Man (The Way I Love You”)” or Dusty Springfield’s “I Don’t Want to Hear It Anymore”. Instead of being surrounded by the warm instrumentation of 1960s soul, though, Lennox is cloaked in thick, icy studio lacquer.

One prominent feature of Lennox’s singing is its muscular quality. It’s a tough, sinewy timbre capable of climbing to some thrilling heights. It’s a heavy voice that can trill in a tight falsetto, but its trademark is a thick, strained huskiness. Her lung power means that even when nestled in the most crowded, elaborate production, her voice manages to punch through the studio viscous. For instance, she emotes with a lone keyboard accompanying her on the album’s second single, “Precious”.

That large voice stretches and flexes. Lennox’s tooling and playing with her voice suddenly become a loose and improvised paraphrase of “Amazing Grace” as she circles around a recurring line of the song: “I was lost until you came”. Then, a crunchy bass punches through, loping alongside a guitar. The track is a driving number that sports a forceful performance that includes multi-layered Annie Lennoxes backing the solo vocal, creating a dizzying wall-to-wall effect of voices that become part of the instrumentation. Clearly, “Precious” takes cues from the late 1980s – early 1990s UK soul-dance music pioneered by groups like Loose Ends or Soul II Soul.

The B-side to “Precious”, included in the Japanese version of Diva, is the equally soulful “Step by Step”. It acts as an apt companion since it links Lennox’s soul affections with soul music’s natural affinity for dance and disco music. It’s a clean and tasteful single similar to what Lisa Stansfield or Lulu were doing at the time. Oddly, the tune didn’t make it to the domestic versions of the album because its smooth-as-silk production would make it fit neatly within them. It’s clear with pieces like “Precious” and “Step by Step” that Lennox was not only following her muse but also looking at what was happening with soul-pop in the early 1990s. Though Diva remains resolutely original and fresh, it bears the marks of what was going on around her musically at the time.

It’s this eccentricity that makes Diva a lasting classic. Case in point: “Walking on Broken Glass”, a gloriously weird pop song with one of the oddest intros: prancing strings, strutting keyboards, and the enigmatic line, “Walking on broken glass”, all of which make the track sound like nothing else on pop radio in 1992.

One of Lennox’s benefits with Diva that eluded her soul foremothers was the advent of MTV and the music video. An artist as dramatic and visual as Annie Lennox was an incredible fit for the music channel. Her videos were mini-films that spoke to the singer’s oft-pretentious yet always interesting visual aspect. Sophie Muller helmed the clip for “Walking on Broken Glass” as a take on Stephen Frears’ 1988 period drama, Dangerous Liaisons. Lennox is joined on-screen by Dangerous Liaisons star John Malkovich—plus comedian Hugh Laurie—as they cavort on a sumptuous set enacting 18th century France. Muller’s direction is quite brilliant: she does quick cuts of the extras, all decadent and ridiculous, while Lennox fumes to reflect the frustration of the lyrics. Because her delivery is slightly mocking and ironic, Lennox’s performance is suitably over the top.

The music video also underscores Lennox’s freedom in playing with her image that female singers in the 1960s weren’t permitted. Even rebelliously subversive singers like the Ronettes or Darlene Love still presented respectable images of elegance and refinement. When it came to singers like Aretha Franklin, the Supremes, or Ronnie Spector, much of the rationale was related to respectability politics. These women were some of the first Black superstars to enjoy mainstream success, buoyed by the dawn of television. Reductive and racist attitudes and stereotypes meant that Black women like Diana Ross weren’t just singers but de facto ambassadors. Despite Dusty Springfield avoiding that racism, she was still hemmed in by gender roles that asked women to be elegant, chaste, and demure. Though she blazed a trail with her beehive and panda eye makeup, she still was always seen in beautiful gowns to look tasteful.

Under Muller’s direction, Lennox’s performance in the music video descends into drunken madness. She portrays a jealous, scorned lover pining for Malkovich’s affection yet chafing under Laurie’s obliviousness. At the video’s climax, she begs Malkovich while crawling on the floor in front of the other party-goers and making an absolute fool of herself. She’s dragged away from the party because she causes a ruckus and creates an absurd scene.

The reason why it’s key to look at the video when assessing the impact of Diva is that in the early 1990s, music videos were integral to pop albums. They were essentially part of the project as a whole, so one could not judge an early 1990s pop album without looking at the visual accompaniment. And more than most, Lennox was adept at expressing herself using that specific visual medium, given that she was a pioneer of the art form in the 1980s.

The music video is key to Diva’s critical, artistic, and aesthetic success, so attention must also be paid to the clip for “Little Bird”, another angular dance number with a funky, pulsing synthesizer. Like the more soulful numbers, Lennox allows for her large, sometimes ungainly voice to strut and preen. As with the other songs on Diva, there’s bizarre oddness to the song, particularly with what Lennox does with her backing vocals (namely, the fluting woo-woos that punctuate the posturing song).

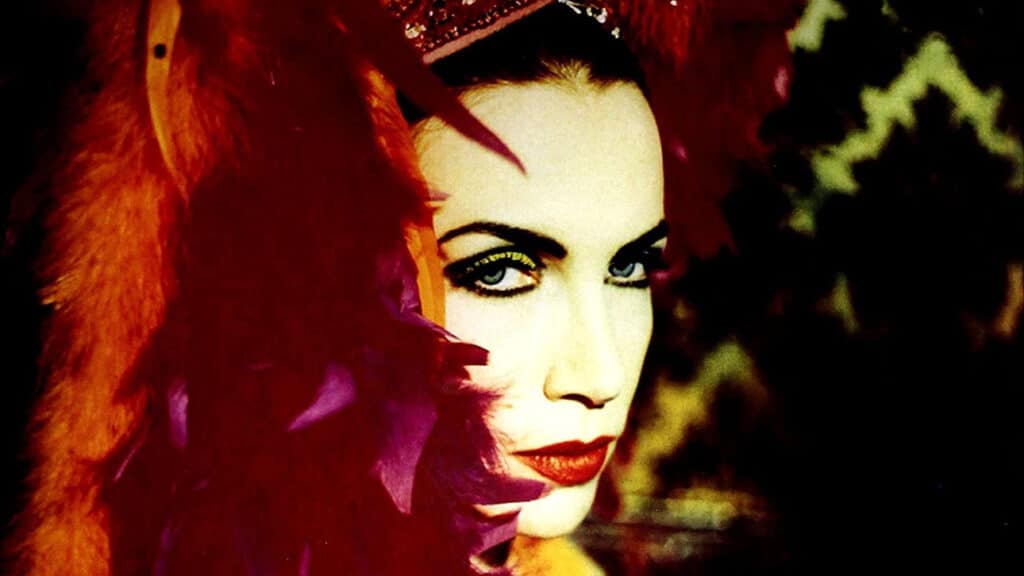

But back to the video. Muller directed this piece as well, and as with the video for “Why”, Lennox is playing up the entertainer aspect of her public persona. She’s not just a recording artist or a singer/songwriter but a performer. Lennox first appears on a stage looking somewhat like Liza Minnelli, and as she vamps and performs, she commands the stage. Suddenly, she is then with an Annie Lennox lookalike from her “Sweet Dreams (Are Made of This)” video, complete with a fluorescent-orange buzz cut and a men’s tuxedo.

Before too long, she’s joined by someone impersonating her Titania-esque persona from “There Must Be an Angel (Playing with My Heart)”, as well as her “Thorn in My Side” character. Next, other faux Annies storm the stage, including the starlet/housewife Annie from “Beethoven (I Love to Listen To)”. Most significantly, the draggy showgirl from the “Why” video glides on stage, followed by the “Walking on Broken Glass” diva, thereby canonizing her solo work as important as iconic as her visuals from her Eurythmics days. The visual references highlight the parallel value of both the visual and audio of the Diva project as a whole. The Muller-directed film companion to the album even won Diva a Grammy.

Annie Lennox once mused that she only listened to “classical music and Dusty Springfield”. She further paid tribute to the legendary Springfield by penning a sweet poem to be included in the liner notes of a boxed set. Lennox’s elegy wrote: “Dusty is singing / Colouring / The drab evening/ Once again / In sparkle gown”. It’s clear that despite the electronic and high-tech filagree of Diva, at its core, it’s a soul-pop record that operates in much the same way that Dusty in Memphis did. How? By setting a new standard for blue-eyed soul that saw yet another wildly talented singer approach the style with depth, understanding, humility, and respect.