From its crest in the 19th century, St. Louis slowly receded into a backwater of the strong currents of change in the United States. Depending on one’s view, a backwater is either stagnant or placid. St. Louis is a bit of both. At times, those of us who live in this region experience localized deluges that push our boundaries beyond our banks and levees, such as championship sports teams or social upheavals like the 2014-15 Ferguson Uprising.

For self-effacing St. Louisans, both types of events feel an inevitable flow of history. The sentiment about St. Louis’ river commerce past is that old money supports cultural institutions like the St. Louis Art Museum (SLAM). Entrance is free, a source of pride for locals. Anselm Kiefer’s recent exhibit at SLAM, Anselm Kiefer: Becoming the Sea, incorporates both the river and the tradition of free access to art. Kiefer required no fees for any part of the exhibit.

Anselm Kiefer: Becoming the Sea is site-specific to SLAM. Cass Gilbert designed the 78-foot-high Sculpture Hall in Beaux-Arts style, modeled on the Baths of Caracalla’s symmetrical layout, Roman arches, and vaults. In this only permanent building from the 1904 World’s Fair, SLAM’s collection displays Kiefer’s “Bruch der Gefäße” (“Breaking of the Vessels”) in one of these vaults. This sculpture is now hidden behind another Kiefer work, “Missouri, Mississippi”, a two-story, multi-paneled representation of the Melvin Price Lock and Dam in Alton, Illinois, and a map of the United States with the Mississippi, Missouri, and Ohio rivers labeled, as are the cities of St. Louis and New Orleans.

As is common in Kiefer’s work, a nude female image floats, or settles, over the American Midwest. The painting commemorates Kiefer’s trip up the Mississippi from New Orleans to Alton, just north of St. Louis, a trip that was stopped by the massive Price Dam, with its temple-like tainter gates set atop the spillway ledge. There are four similar paintings mounted beside this one in the hall.

I first visited the exhibit on a late afternoon. Something odd happened when sunset filled the space. Darkness arose at the edges of the sunbeams. Parts of the room glowed while others receded into shadows.

Kiefer’s paintings are highly textured, often with large pieces peeling away from the canvas. He uses gold leaf, oxidized-copper blue green, opal green, and black. The nearly horizontal fading sunlight darkened the black, used largely for tree trunks, branches, and leaves, to the point that sections of the canvases nearly disappeared into solid black planes. Both tones of green glowed with something close to phosphorescence. The gold glittered as if to surge off the canvas.

Later, after my pass through the galleries with Kiefer’s works ranging from the 1970s to the present, the posters for sale in the gift shop startled me. They were full of dazzling nuances of color, not the darkened, almost scotopic vision of crepuscular Sculpture Hall.

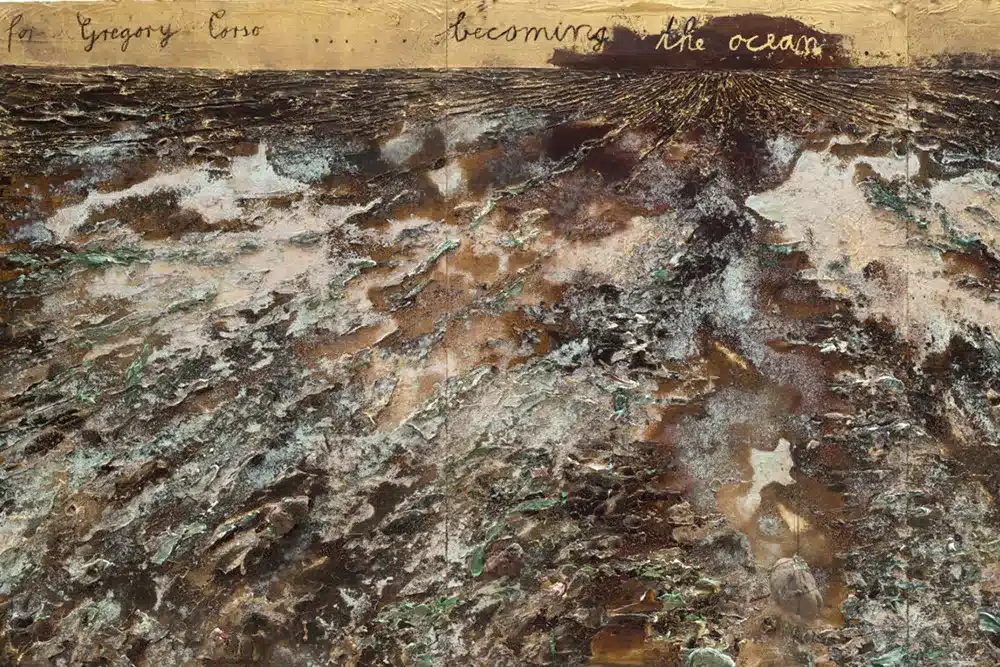

A quote from the Beat Generation poetry of Gregory Corso dominates “Fūr Gregory Corso”: “Spirit is Life. It flows thru the death of me endlessly like a river unafraid of becoming the sea.” The quote also gives the exhibition its title. One of the five 31-foot-tall paintings in “Fūr Gregory Corso” is a turbulent waterscape that fills around 90 percent of the canvas, with a sliver of gold sky at the top that also holds the Corso quote. According to Kiefer, this water is the Mississippi, though given the expanse of the canvas with whitecaps and blue-green coloring, the sea must be evoked, as if the river and the sea could be mistaken for variations of each other.

Another of the five mural-sized paintings, “Lumpeguin, Cigwe, Animiki”, splits horizontally. An arched steel-truss bridge atop brick piers dominates the bottom half. The water below roils. A band of dark trees bounds the distant bank. Having grown up in the St. Louis area, I see in the painting the rectangular box girder Chain of Rocks Bridge at the northern tip of the St. Louis riverfront.

Below it lies the Chain of Rocks, a natural outcropping of an unnavigable granite shoal. The top of the canvass is entirely golden sky with three female winged Native American beings: Lumpeguin (water sprite); Cigwe (Thunderbird); and Animiki (Thunderbird). Though not necessarily female in the original stories, or even associated with rivers, let alone the Mississippi, Kiefer presents the three figures as protectors of waterways.

The tacked-on nature of these figures made me uneasy, not for the cultural appropriation aspect, but for the Romanticism that I find in Kiefer’s work. Though known for direct confrontation with German anti-Semitism, Nazism, and the Holocaust, there is a naïvety in Kiefer’s view towards nature, especially rivers.

In two of the large paintings, “Am Rhein” and “Anselm fuit hic”, Kiefer gives us a distant view of the Rhine framed by thick black woods reminiscent of Kiefer’s childhood Black Forest. The trees wend inward enough almost to close off the sky with a tunnel of branches. In these paintings, the river is a faraway, idyllic place.

Anslem Kiefer was born and raised near the Rhine, which gave him a very different riparian memory than I have of my birthright in Mississippi and Missouri. For me, as for T.S. Eliot, another St. Louis son, the river is both a natural fact and a dangerous god. I cannot see the river as a refuge, as Kiefer does, but as a threat. I’ve lived on bottomland submerged in yearly floods. The river carries the waste of two-thirds of the continent to the “dead zone” of the Gulf. The sea is no afterworld for the river, either, but battles against freshwater and its land.

Science gives us the poetic term “marine transgression” to describe rising sea levels, disappearing land, and the loss of river length. Like Corso and Kiefer, I, too, love rivers, but I fear dissolution in salt water. No one who truly loves rivers can also love the sea.