At the risk of infuriating diehard doomsayers, has there ever been a better time to be a reader? Some may point to other periods that seem more appealing from a literary standpoint (forgetting that most of those books, even if out of print, are easier to get now than they were decades ago). They could convincingly argue that the bestseller lists are something of a genre wasteland these days, with serious literary fiction getting ever more pigeonholed as a specialty taste.

Here’s the thing, though: Despite the major publishing houses playing a highly risk-averse game, much like the film industry, the books keep coming. There are more scrappy publishers, inventive authors, nifty new bookstores (one probably opened in your town not that long ago; go check it out), and compelling stories than we will have time for, but we can do our best with what time we have.

That’s especially the case when it comes to cultural writing. These days, it seems there is a book (or books) for every artist, writer, band, or movement that ever existed. We found a great many of those which we loved, from J. Hoberman’s history of the 1960s’ New York avant-garde to Tanya Pearson’s account of female rockers in the 1990s, Steven Rings’ exploration of Bob Dylan’s music, Ron Chernow’s gargantuan yet lively biography of Mark Twain, and Stereogum writer Chris DeVille’s book on 21st century indie rock (do you have thoughts on Death Cab for Cutie? This is the book for you).

W. David Marx takes a somewhat bleaker view than those other books, arguing, in essence, that the culture is zombified at the moment. (Who was big ten years ago? Taylor Swift and Beyoncé. Who’s big now? Taylor Swift and Beyoncé.) It’s an enlivening read nonetheless.

We also got knocked sideways by some of the new fiction out there. No, we didn’t check out the latest John Grisham, David Baldacci, Nora Roberts, James Patterson, or Lee Child (yes, they’re all still banging out bestsellers). We were impressed by the inventiveness of some novelists—particularly Ian McEwan, Patricia Lockwood, and Mark Danielewski—who all found new ways to tell the human story.

Enough throat-clearing. Time to get reading with PopMatters Best Books 2025, presented in alphabetical order by title. – Chris Barsanti

Blank Space, by W. David Marx (Viking)

It’s been exactly a quarter of this culturally discombobulated, postmodern century. Right on cue, culture writer W. David Marx sweeps in to offer a partial explanation for why American (and global) culture became a stagnant phenomenon devoid of originality or political radicalism. His Blank Space, a cultural history of our century so far, is a scathing indictment of the neoliberal telos, whose primary cultural purpose is to destroy critical thought and monetize everything, from opinions to appearances.

Refreshingly snappy and at times ruthless, Blank Space parses the past 25 years through a masterfully woven narrative of how the so-called millennial generation formed its worldview and, accordingly, the culture of today. Fiercely argumentative and extremely funny, Marx articulates a generalized theory of contemporary cultural production through methods and tactics employed by individual superstars and their cohorts. The likes of Jay-Z, Lady Gaga, and especially tech bros all suffer hilarious takedowns.

In his mapping of how uniformity and banality came to dominate the charts, Marx acknowledges (neo)liberalism and postmodernism as the forces driving the degradation of culture.

Still, critics point out Blank Space is “merely” a popular book offering a context-specific, contained narrative of pop production. It is true that Marx’s latest work doesn’t succeed in the herculean task of decoding how reality is created through symbols and narratives. Nevertheless, it is a marvelous, uproarious page-turner that explains plenty, and a good starting point for understanding where our culture is today. – Ana Yorke

Bread of Angels, by Patti Smith (Random House)

The legendary writer and musician (and photographer and artist) Patti Smith shows scant signs of slowing down, even as she approaches her 80s. She has just wrapped up a US and European tour celebrating the 50th anniversary of her iconic 1975 debut album, Horses, and earlier this year, she released a spiritual sequel to 2010’s National Book Award-winning Just Kids, this 2025 memoir, Bread of Angels.

Whereas Just Kids mainly focuses on her relationship with photographer Robert Mapplethorpe and their ascent to fame in the gritty art and music milieu of 1970s New York City, Bread of Angels delves into her childhood in Philadelphia and New Jersey, as well as her time in Detroit with her late husband, Fred “Sonic” Smith. Her childhood, marked with poverty and illness, nevertheless helped shape her artistic pursuits, as her imagination, fuelled by books and classical music, held sway.

Later, she discovered Rimbaud, Bob Dylan, and the Beats, and there was no turning back from her destiny as the pioneer of poetic punk. She made her mark on the music world, and then she

retreated into a quiet married life. However, she never loses her “rebel hump”, that

defiant drive, to keep creating.

She eventually reemerges into the public eye, despite many tragic losses of family and friends, or maybe because of them: touring and writing became a way to heal and move forward. Patti Smith’s singing and writing are equally suffused with a glorious gravity, and it’s a joy to continue to immerse oneself in her transcendent art. – Alison Ross

The Delicate Beast, by Roger Célestin (Bellevue Literary Press)

Roger Célestin’s debut novel, The Delicate Beast, consists of over 400 pages of dense text, circuitous paragraphs, and serpentine sentences imbued with seemingly endless, granular detail. Does Célestin’s narrative merit the commitment that reading this novel entails? Absolutely.

The plot of The Delicate Beast could be considered well-worn – individuals who barely survive a brutal dictatorship are scarred for life. In addition, the density and granularity of the narrative could be considered excessive. Such critiques, however, are misplaced. Engagement with this novel is satisfyingly worthwhile. The Delicate Beast provides a unique pleasure due to Célestin’s masterful writing style.

He tells his tale in exquisite, crystalline detail. The description of a child’s golden days in a Tropical Republic provides an intimate sense of living through this idyllic period and the overhanging approach of the family’s fate – a childhood of “bliss and … brutality.” The post-Tropical Republic narrative details the protagonist’s travels and his striving to live in a comfort zone detached from his past.

The author of more than 100 academic books and articles, Célestin presents in his debut novel a timely tale that shows the establishment of autocracy as inexorable once the process has begun. What sets The Delicate Beast apart is Célestin’s bravura writing, which is unusually confident and risky for a debut novelist. This novel deserves and richly rewards attention. – R.P. Finch

See also: “Roger Célestin’s ‘The Delicate Beast’ Will Devour You“, by R.P. Finch.

Everybody’s Head Is Open to Sound, Anaïs Ngbanzo, Ed. (Editions 1989)

Tom Wilson was a young, black Harvard graduate who founded a tiny jazz label that issued the visionary debut recordings of Sun Ra, Cecil Taylor, Donald Byrd, and crucial early works by John Coltrane. He would ultimately move to the Big Apple, join Columbia Records, and produce the milestone early classics of Bob Dylan (“Like a Rolling Stone”) and Simon & Garfunkel (“Sounds of Silence”) before joining MGM Records to sign and produce Frank Zappa’s Mothers of Invention, the Velvet Underground, and Nico.

The Animals, the Blues Project, Soft Machine, and the mega-selling Irish folk group the Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem are among the other acts whose creativity and careers were fostered by a man who has rightly been called “the greatest record producer you never heard of”. Now, thanks to Éditions 1989, a Paris-based non-profit dedicated to publishing “biographical books of overlooked figures”, we have a long overdue dive into the remarkable but brief life of Tom Wilson, a man who did as much as anyone to shape the sound of jazz and rock in the latter part of the 20th Century.

Everybody’s Head Is Open to Sound is the first-ever collection of writings about Wilson, edited by Anaïs Ngbanzo, founder of Éditions 1989. Through newly commissioned essays by music historians Wolfram Knauer and Richie Unterberger, journalist Ignacio Juliá, and essayist Pacôme Thiellement, this book explores Wilson’s crucial role in documenting avant-garde jazz and producing key folk-rock recordings of the 1960s, before his premature death at 47. It also features “A Record Producer Is a Psychoanalyst with Rhythm”, a rare, full-length, circa 1968 interview with Wilson from The New York Times Magazine, along with a selection of previously unpublished photographs.

With his taste and track record, Tom Wilson certainly deserves the kind of fame afforded to his contemporaries, such as Phil Spector and George Martin. Perhaps this fine book will do what its publisher intends: shine a deserving light on a sadly overlooked giant of 20th-century music who passed way too young. – Sal Cataldi

See also “How the Remarkable Tom Wilson Shaped Jazz and Rock“, by Sal Cataldi.

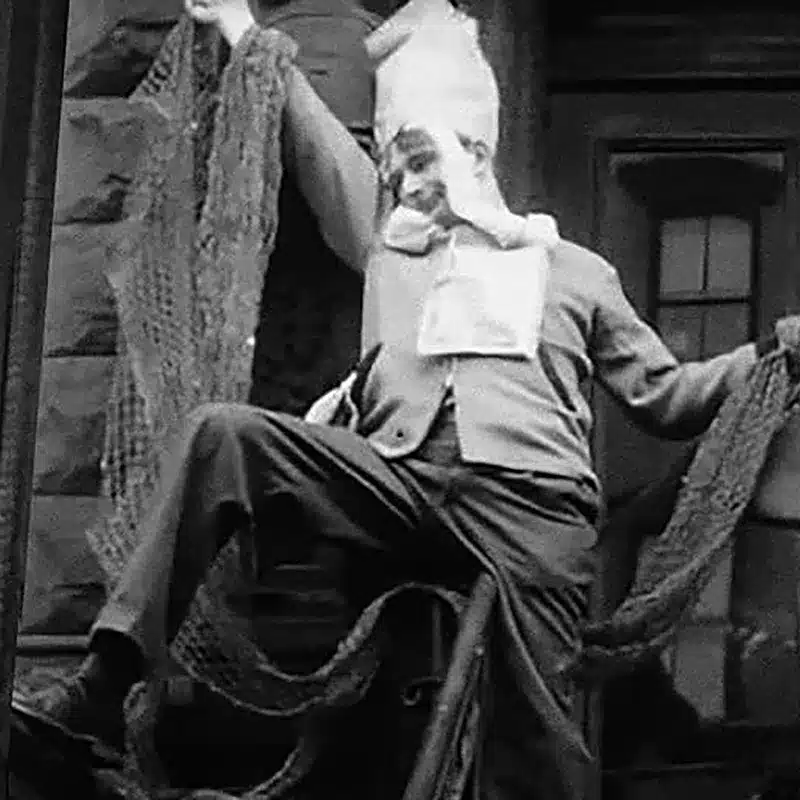

Everything Is Now, by J. Hoberman (Verso)

New York City of the 1960s was a cauldron of avant-garde ferment and artistic innovation. The creative vitality of this era was passionately reported by the scribes of New York’s many culture weeklies, publications like The Village Voice, The East Village Other, Open City, The Paper, Cue, The New Yorker, and the deliciously titled Rat Subterranean News. Now, longtime Village Voice culture and film critic J. Hoberman has provided us with the ultimate chronicle of this still-influential explosion of creativity in Everything Is Now.

Underground film, performance, and Pop Art, experimental theater and happenings, poetry and ‘zine and comix culture, free jazz, and an edgy new brand of rock are just a few of the art forms that were being forged by a new breed of artists living in this gloriously low-rent era of Metropolis. It was a time long gone when young visionaries could survive, and indeed thrive, on ridiculously low-budget lifestyles, when they were slaves to their muses and not the unquenchable greed of landlords.

In its 400-plus pages, Hoberman expertly demonstrates how these varied subcultures were birthed in cold-water lofts, coffeehouses, and tiny storefront galleries and theaters. Ideas and expressions forged in these circumstances would coalesce into the unified “counterculture” later in the decade. It’s hard to imagine a book more densely packed with information that is so eminently readable. – Sal Cataldi

See also “‘Everything Is Now’ Digs Into NYC’s Avant-Garde Ferment“, by Sal Cataldi.

Flesh by David Szalay (Scribner)

David Szalay’s Booker Prize-winning novel is linguistically spare, where anxiety, uncertainty, and unfathomable emotions roil beneath the surface of its seemingly placid and imperturbable protagonist, until it feels as if a detonation is unavoidable. István is a Hungarian kid whose flat passivity and inability to comprehend or connect with others leave him largely undisturbed, floating through a life that seems exciting on the surface but leaves him cold.

After a fight with the husband of an older woman he was having an affair with, leaves the man dead, he spends a few years in prison before joining the army for a stint in Iraq, and then works as a club bouncer and private security guard in London. Even as calamities pile up (people he knows tend to die) and he achieves spectacular wealth through another affair with a married woman, little causes István to reflect or respond in conversation with anything besides “Yeah” and “Okay.”

Szalay does not use István’s flatness to present him as some avatar of bored coolness, but rather a numbed man who starts to understand he is missing out on something beyond his comprehension, only too late to do anything about it. Although Flesh reads like an uncomfortably close-to-home rendering of 21st-century disassociation and rootlessness, Szalay’s clarity of language and humanist insight give it an out-of-time quality that will likely make it as potent 50 years from now as it is today. – Chris Barsanti

Girl on Girl, by Sophie Gilbert (Penguin)

The Atlantic writer Sophie Gilbert explores in her debut book Girl on Girl, a broad-reaching and exhaustive excoriation of the layers of sediment that weigh on the modern woman’s body, sexuality, and psyche. Gilbert’s meticulous research shows that there was no place for women to hide in the 1990s and 2000s, an age that shaped how men and women judge, think, and see each other and ourselves. Its title comes from a popular porn category, a medium that Sophie Gilbert argues is “the defining cultural product of our times.”

Girl on Girl is at its most successful when documenting the spiky media landscape of the era, reserved for young girls. Teen stars like Lindsay Lohan, Britney Spears, and Paris Hilton were relentlessly shamed for what male commentators saw as their sexuality, even though they were trying to conform to the standards of the time. After the early 1990s wave of feminist, grassroots punk bands like Bikini Kill or Sleater-Kinney, younger, sexier singers like Britney Spears or the Spice Girls popped up to offer a glossy, fun version of feminism that promised enlightenment through fundamentally indifferent actions. Girl Power, the Spice Girls’ message, was propped up as a capitalist ploy through merchandise, Gilbert suggests, and stood for basically nothing.

Girl on Girl is often disheartening only for the mountain of misogyny Gilbert presents — but it’s somehow not a heavy read. Research is abundant on how American and British society has mistreated women, but also an emphasis on their iconoclastic art. Society goes through waves of progress and regression — our current era is a bleak nadir — but logically, it has to pivot. Even though it will take unlearning who gets to tell which stories, Gilbert ends, “I do fundamentally believe art can occasionally enable a top-to-bottom reconfiguration of everything we’ve ever found ourselves believing.” It’s one of life’s greatest pleasures, even. – Sam Franzini

See also “Sophie Gilbert Excavates Millennial Misogyny’s Buildup“, by Sam Franzini.

Good and Evil and Other Stories, by Samanta Schweblin (Picador)

Fiction of horror and extreme suffering has become mostly redundant in our supremely horrific age. Still, Samanta Schweblin, perhaps the most prominent Argentinian writer of her generation, reigns supreme as a mistress of short stories laden with atrociousness and pain. Her latest collection, Good and Evil and Other Stories, is another triumph on the heels of A Mouthful of Birds (2009) and Seven Empty Houses (2015, translated in 2022 by Megan McDowell).

Her latest collection is a melange of six stories that, by Schweblin’s admission, read as more personal and autobiographical than the predominantly supernatural or dystopian plots of her previous work. Substituting intimate turmoil for sprawling dread, Schweblin again succeeds in deploying her sparse narratives about strange situations to wrestle with the uncanny at the heart of our existence.

Without revealing any of her customarily incredible twists, death and irreversible life changes take center stage throughout, propelling a thematic exploration of guilt, grief, and fear. As is typical for Schweblin, her characters keep struggling with a world that seems other to their very existence, hanging by a thread while things around them fall apart. At the heart of it all, however, lies not cynicism, but a surprisingly tender ode to humanity and its many misgivings. – Ana Yorke

Mark Twain, by Ron Chernow (Penguin Press)

The long march of biographer Ron Chernow through the ranks of American icons—Alexander Hamilton, Ulysses S. Grant—not only seems to lead inevitably to Mark Twain (Samuel Clemens’ pseudonym and persona quickly overtook the use of his real name) but could cause a kind of torpor in the reader. There is, after all, something marble statuary about this procession of characters, which can feel dutiful or the book equivalent of Ken Burns.

However, Chernow’s book more than deserves its inevitable position on the bestseller list due to the author’s capacious eye for research and telling detail as well as the fiery sparkplug energy of his subject. A scrappy autodidact with a somehow wry yet pugilistic approach to writing and life, Twain is presented as a mass of contradictions. Sentimental yet clear-eyed, Twain rhapsodized about growing up a Southerner in the idealized river town of Hannibal, Missouri, fought in a Confederate militia, and presented a sometimes cartoonish take on black characters but also viciously satirized backwoods ignorance, became a tub-thumping champion of civil rights, and humanized those same black characters more than other white writers were willing to do.

A world-travelling lecturer who essentially invented the modern literary celebrity, threw off opinions by the fistful, and tore through life with a manic energy, the Twain presented by Chernow is a fascinating tangle. – Chris Barsanti

The Martians, by David Baron (Liveright)

In a better universe – where HBO is never called Max, everyone can agree on which prestige show we should watch, and The Walking Dead has never happened – a late season of Julian Fellowes’ The Gilded Age series would work details from David Baron’s The Martians into multiple episodes. Incredible as it sounds, for about 15 years, a good-sized slice of the American public—including many upper-class denizens who frequented the theater and lecture halls for edification and improvement—was not just convinced there was intelligent life on Mars, but desperately wanted it to be so.

People were eager to look up and dream. The Victorian world they inhabited was rife with possibilities, but so was fear of the unknown. While a smart, popular history of a mania, The Martians provides a vivid sketch of turn-of-the-century America, where “science had banished” the religion, superstitions, and “enchanted beings” that once pervaded people’s conception of their world, replacing them with “existential disorientation”. New inventions and media were adding more disorder to the already chaotic Industrial Age.

Despite the implacable stubbornness of the Mars dreamers in the face of tut-tutting scientists, The Martians fails to find a dark side to this craze. Lightly mocking without being denunciatory, Baron appears very familiar with and not overly worried about his countrymen’s habit of occasionally getting all too worked up about things. While fantasizing about magical, benign creatures beyond the heavens might not have been the most productive response to societal churn, class strife, and economic disruption, at least it was not destructive. – Chris Barsanti

See also “‘The Martians’ Probes the First Time Americans Went Nuts for Aliens“, by Chris Barsanti.

Our Beautiful Boys, by Sameer Pandya (Ballantine)

A lot has happened in a decade since I reviewed Sameer Pandya’s 2015 collection of short stories, The Blind Writer, yet Indian identity remains a component of Our Beautiful Boys. Pandya has a gift for capturing dialogue among different populations: teens, professors, couples, families, and even football players. He writes not as an outsider overhearing the most intimate moments but as an insider with a beautiful approach to writing from a place of knowing. The dissolution of marriages, adolescent uncertainty, intergenerational feudalism, tenure-track politics, workplace drama, and school toxicity are all tackled creatively here.

At its most vulnerable places, Our Beautiful Boys takes on the complexity of privilege, racial passing, stereotypes, discrimination, hierarchies, and the model minority. Pandya goes where few writers do, mining the pain of parents who may have lived their whole lives in the US but still wrestle with America’s existential crises.

Many cultural wars are happening concurrently in the United States in 2025, but the question of racial privilege may be at the top. As the Trump administration actively dismantles DEI programming and race-related collegiate policies, there has never been a more critical time for a writer to tackle the everyday realities of racial reckoning. Pandya has taken on this dirty work in Our Beautiful Boys. – Shyam K. Sriram

See also “Sameer Pandya’s ‘Our Beautiful Boys’ Is Vulnerable and Powerful“, by Shyam K. Sriram.

Pretend We’re Dead, by Tanya Pearson (Da Capo)

Tanya Pearson’s Pretend We’re Dead, about women in rock music, wears its heart on its flannel sleeve. As one of her University of Texas Press mates – her book on Marianne Faithfull inspired me to write one on Alanis Morissette – I might be biased, but I’m also happy to say Pearson’s work is both deeply serious and a raucous good time. Her scholarship is thoroughly enjoyable even as it probes darker realities.

Pretend We’re Dead’s assessment of the world of women in rock music during the 1990s includes Pearson’s characteristic mix of wit and unflinching honesty, making even the grittiest aspects of the industry feel alive and engaging. While it’s often a necessary, depressing history lesson, the author’s voice ensures it’s never a slog. The book brims with her humor and clarity.

Pearson adds to that legacy of women in rock music while making it her own. She doesn’t just assemble interviews; she weaves them together with commentary that’s equal parts incisive and hilarious. Her bluntness is a breath of fresh air, and her interviewees are clearly charmed by it because they tell her the whole ugly truth in return.

Pretend We’re Dead proves that the spirit of 1990s women in rock music is still alive and fighting. Here’s hoping that the oldsters celebrating their ‘90s nostalgia and the youngsters trying to make it new keep turning up the volume. – Megan Volpert

See also “Women in 1990s Rock Music Are Far from Dead“, by Megan Volpert.