In 2009, electronic music was 20 years beyond England’s second summer of love in 1989, the year when waves of four-on-the-floor reverberated from Manchester to the moon and set in motion a long arc of momentum that can now be said to be completely decentralized. If you’re having troubling chasing the concordant memes of electronic music in 2009, you’re not alone. Even an obsessive with no distracting family, social, or economic preoccupations would have a hard time keeping up.

Back in the acid house moment, it would be easy for Luddite rockists to chide, “I don’t listen to techno because it all sounds the same.” Now, you’d be hard-pressed to find any cogency amidst the variety of synthetic noises out there. Sure, there will always be pasty-faced demagogues rallying around guitar dinosaurs (U2) and new-school fogies (Jack White). But more people are listening to electronic sounds now than ever before.

The radio has been completely electrofied, the most it has been since the 1980s, for better or worse. And while the current crop may slightly evoke the aforementioned decade, there’s also a touch of catching up with 2002’s 1982-grave-robbing schemas. Shakira’s DFA-like synthpop single, Owl City’s blatant Postal Service rip-off, Lady Gaga’s Super Bowl-scale reimagining of electroclash, Electrik Red’s proselytizing of Sugababes into depraved sex kittens, and Christina Aguilera’s plans to work with Ladytron all point to a pop present that could be interpreted as a zeitgeist with either a paucity of ideas or a knack for reformulating alternative notions of pop buried by the postmodern age’s information surplus.

With the continued reign of Auto-Tune, pop music exposes melisma for the mechanical concoction it is, democratizing American Idol pick-a-note-ism for robots. Still, the promise of technological fusion in pop seemed to have been squandered in 2009 by stoopid-ly gigantic T.I.-style power chords that resembled bland Darude clubism rather than any kind of real vanguard as imagined in the halcyon days of Timbaland and the Neptunes (both of whom continue to desecrate their legacy by staying active). Similarly disappointing, grime moved out of the pirate stations onto the main dial in the UK, but #1 hits by Dizzee Rascal and Tinchy Stryder found those two adapting to the charts rather having their radical energies welcomed by the mainstream.

The broad topographical field known as “indie” was also littered in electronic sounds, boasting a diversity as vast as Animal Collective, Passion Pit, Fever Ray, Junior Boys, Fuck Buttons, the XX, and so on. The one “new” sound to emerge out of electronic indie pop was a barrage of warbled, sun-baked cassette patches and bubblegum resuscitations of unconscious sound from the junk food television of hipster youth (Ducktails, anyone?), a TV Carnage DVD mashed in a blender and purposefully retracted from the sheen of today’s digital eternal sound. In other words, a less bookish and less calculated hauntology for a younger generation. Once, this may have just been called lo-fi, but the ubiquity of cheap laptop software would seem to indicate that all the line noise is a deliberate choice.

Dubbed “hypnagogic pop” via an article in The Wire by David Keenan, the broad umbrella of sounds came to include those disenchanted with the noise scene (namely the Skaters) and those just fascinated by the morose sadness of a rear view lens (Memory Tapes/Memory Cassette/Weird Tapes, Neon Indian, Delorean). Impressively, the hypnagogic pop stars were able to find possibility rather than stasis in ancient putrid lite FM and new age — no small feat. Ironically, this all came about at the moment Black Moth Super Rainbow hooked up with a major producer (and, apparently, Ariel Pink too), but they seemed to survive the split alright, as their inclusion on the list below illustrates.

Though Weird Tapes did find a fine way to incorporate a Legend of Zelda sample, those subconscious sources of electronic influence — buzzy chiptune sounds — found a more comfortable home in the overlapping worlds of dubstep and wonky. Joker’s Purple Wow Sound mix seemed to give as good a name as any to the sound, and it was all over releases this year, juxtaposing the brown-note-anticipating low end with high-pitched Nintendo freakouts. There was still all manner of epileptic shudders and fuck-shit-uppery wobble in dubstep (Caspa, Broken Note, Cookie Monsta, et al.), but the genre’s horizon continued to shrink further in the distance as new bodies stretched the sound every which way. The year of Joy Orbison’s “Hyph Mngo” was still owned by singles, but a selection of versatile interests also tried their hands at the long player, either as album-length statements (Martyn, Starkey, FaltyDL, 2562) or collections of previous works (Shackelton, RSD).

Planet Mu’s dubstep at times got so mercurial that it sounded like intelligent dance music with emphasis on the “dance” rather than the “intelligent” (ditto Redshape’s techno on The Dance Paradox). However, the most unexpected fusion was that of dubstep and funky house, now garnering the preliminary tag of “funkstep”. Singles under this tag by Donaeo, Cooly G, Kode 9, and Geeneus were more upbeat and R&B-inflected than dubstep, but seemed to share the warbly genre’s crooked gait.

The past continued to be reanimated in the form of reissues in 2009. Kraftwerk, pioneers of just about all that followed, finally got around to the remaster they’d been promising since 2004, but lesser-knowns from the hardcore continuum (Shut Up and Dance, Terror Danjah, El-B, Bizzy B, Roll Deep) were also celebrated, sometimes for the first time on CD (just like the Beatles!). Some stellar house mixes also saw double-disc action with Pépé Bradock’s Confiote De Bits and DJ Koze’s Reincarnations spinning on repeat for many who couldn’t resist their insistence. Hyperdub celebrated five years with a high profile double-CD, Kompakt marked a decade with little fanfare, and Warp turned 20 with a canonical box set objet d’art, which, at this point, is pretty much what you’d expect from Steve Beckett and company.

Last year’s year-end retrospectives saw much proclamation of the death of minimalism, and while it has quieted down a bit (pun intended), with the exception of a few notables releases on Echospace, Modern Love, and the like, not much has come along to take its place (least of all some kind of maximalism). Deep house (Moodymann, Black Jazz Consortium) continued to get deep, electro had a few surprise knockouts (Harmonic 313, Linkwood, DJ Hell), several noteworthy supergroups synergized their talents (Moritz von Oswald Trio, Lindstrom and Prins Thomas, Moderat), and big ballers pumped out adequate though hardly compulsory releases (Basement Jaxx, Röyksopp, Simian Mobile Disco). On the fringes, hauntology seemed to split its time between Broadcast-related projects (Broadcast and the Focus Group, Roj, Seeland), Raster-Noton (SND, Alva Noto) and Miasmah (Kreng, Elegi) upped their games, and there was a wealth of intriguing entries into the arcane (Tim Hecker, Vladislav Delay, Somfay, Syntheme) and otherwise unclassifiable (Spoonbill, Matias Aguayo’s latest).

To cut a long story short, we have no idea where the hell electronic music is going in the next decade, but if you can’t find something in the wide stew of sonics out there to get excited about, check your pulse. You’re probably dead.

So here’s what we could distill to a list of ten selections.

10. Brock Van Wey – White Clouds Drift on and On [Echospace]

Brock Van Wey unapologetically daubed his impressionist ambient soundscapes in a surfeit of colors long thought extinct in the world of electronic music. Somewhere between the ethereality of an early 4AD record and a starburst version of Bowery Electric’s Beat (without, of course, the beat), White Clouds Drift on and On is a mix both gentle and restless. The whirlwind of emotions composed by Van Wey (also known as Bvdub) are direct and open, rather than retracted and masked, a rare quality, especially along the Echospace axis from which it emerged. Van Wey’s embrace of melodrama feels less a plea for emotion than a bellowing cry from inside, a Douglas Sirk Technicolor envisioning of affectation as a formulation of style exercises.

Perhaps to legitimate matters in the dubtronic community, Stephen Hitchell’s Intrusion remixes the entire album in reverse order on disc two, but it’s obvious that Van Wey opened a door for Hitchell as much as Hitchell did for Van Wey. The sensory panorama of the Intrusion “shapes” on disc two are easily as lovely and viscerally stirring as Van Wey’s, but with more of a skeletal rhythmic structure and echo-plated aura. Overall, it’s the best either have yet offered. – Timothy Gabriele

9. 2562 – Unbalance [Tectonic]

While some of the loveliest, most seductive dubstep (and related) sounds materialized in small doses during 2009 — Cyrus’s “Space Cadet”, Mount Kimbie’s “Maybes”, and Burial’s “Fostercare”, for example — 2562’s Unbalance stuns in long player format. Re-engaging Brit 2-step is omnipresent of late, and just as he did on 2008’s debut LP Aerial, Dave “2562” Huismans blends dub and techno tendencies for most of Unbalance, but it’s a warmer trip this time. “Lost” is positively mesmerizing — the clacking and clopping beats slow to half-pace, while bells, stuttering keyboard tones and vocal samples are weaved around rubbery, subtle bass prods. It’s easy to head back to the record primarily for temperate moments like these — they’re everywhere — but if you peek back only for the glitzy organ swathes and slick programming in “Love in Outer Space”, you’d miss out on uneasy trips like “Who Are You Fooling?”, where ambient techno is thankfully still very much on Huismans’ agenda. – Dominic Umile

8. Bibio – Ambivalence Avenue [Warp]

On a tree-lined street in Central London, Bibio’s Stephen Wilkinson greets the day, clad in late-summer gear and gazing optimistically at a point in the distance. He looks as if the world is his oyster. Not six months after Vignetting the Compost took us around the same lovely fields he’d been roaming for half a decade, Bibio moved to Warp and unleashed his experiment, a dizzying show of genre-play less notable for its actual music than for the impact it had on everyone who’d already written him off. All of a sudden, Wilkinson wasn’t just exploring his guitar’s sonic possibilities, but the ways in which he could use it to participate in a dazzling musical tradition.

He played blue-eyed soul, futuristic urban pop, amped-up versions of his own thatched folk and amazingly good instrumental hip-hop like he had everything to gain, and with mystifying confidence. So assured was he, in fact, that he let his voice fly high and adopt the protean role of his guitar, after years of withholding it. And just as quickly, Bibio found himself with an audience of people as giddy about his music as he was. The prevailing feeling on Ambivalence Avenue isn’t ambivalence at all, which implies dispassion. It’s the excitement of a highly creative artist who didn’t want to choose, who saw his options, said “no regrets”, and ran as hard as he could after all of them. – M.R. Newmark

7. Gui Boratto – Take My Breath Away [Kompakt]

Hear that on “Besides”? That’s the sound of 1,000 tech conventions and car commercials launching. It’s optimistic, yet oddly sterile. The same could be said of Gui Boratto’s music, sparkly techno that soundtracks a beautiful sunny day as seen through the large window from a cleanroom. The cover art for Take My Breath Away — easily one of the best cover images of the year — depicts such a scenario, as respirator-equipped children appear oddly unfazed in a meadow which, upon closer inspection, is artificial. Like a Pixar film, however (and equally as arresting and ultimately uplifting), Boratto wrests unlikely strides of emotion from his germ-free origins, whether it’s the life-passing-by observations of “No Turning Back”, or the cool gusts of percussive noise on “Opus 17”.

Boratto got his start in the advertising world, which isn’t at all surprising, considering the carefully crafted moods of Take My Breath Away. However, like a great pop artist, Boratto’s skill is in his ability to metamorphose these frames of reference into something else, something truly unique. – David Abravanel

6. Black Moth Super Rainbow – Eating Us [Graveface]

Granted, Black Moth Super Rainbow did not exactly reinvent the wheel with their 4th album, but, with Dave Fridmann (Flaming Lips, MGMT) behind the consoles, Eating Us is definitely the best-produced album yet released by the Pittsburgh collective. While the somewhat lo-fi aspect of their sound up to this point was a large part of their charm, little or nothing was lost in the transition to real studio recording.

The vocoder retains its sepia-toned ethereality and the gobs of synth distortion fill the same aural gaps they did on 2007’s Dandelion Gum, but the filters and effects no longer veer out of sight. It is their most accessible and linear album in terms of production and songwriting, though their surreal lyricism may “freak out the squares” as they were intended. For such a lofty, detached sound, Black Moth Super Rainbow actually feature some fairly bluesy lyrics, asking “Iron Lemonade” to “wash my friends away” and proclaiming they were “born in a world without sunshine” in the opening track. If this was a work of depression, depression has never been this much fun. – Alan Ranta

5. Dan Deacon – Bromst [Carpark]

As with Fuck Buttons’ Tarot Sport, Dan Deacon’s Bromst kept the album format’s partial exquisite corpse alive by a marathon methodology. Far from being diversified and regimented, Bromst is an album of beautiful consistency, transparently syncopated to machinal programming like it boiled down jouissance to a mathematical formula (with the exception of “Wet Wings”, which transforms a folk sample into a flock of migratory birds). Deacon even set up many of his tunes of assaultive glee to synch with a player piano. It’s no surprise that hipsters are beginning their backlash against Deacon, once their patron saint of juvenilia n’ whimsy.

Bromst marches in defense of the loudness war, on what many fidelity snobs would dub “the wrong side”. However, the album’s authority is not solely in the massiveness of its sound, but in the richness of his melodies. Deacon emotes with the euphoric power chords of M83, arpeggiates with the manic chiptune splendor of Koji Kondo, xylophones like a wind-up monkey doll with a rainbow coming out its ass, and blurts glossolalic warped chants into the microphone with the pitch-bent sway of Kevin McCallister’s Talkboy.

Yet gripes about Deacon’s manchild persona should evaporate in those who sit down with the album and notice its complex interplay of broken nursery rhyme carnivale and momentously-timed explosions of synth-bliss pop rapture. Bromst is the first recorded instance of Deacon pouring his heart all over a record, the way he does in nearly every performance he has ever done in his last five years of consistent touring (“Hello, my ghost, I’m here / I’m Home” go the album’s opening lines). It’s an instance of transforming the pre-pubescent elation innate in discovery and novelty, always a transfixion of Deacon’s, into something that’s not onanistic (as it has been in the past with him), but actually transcendent. – Timothy Gabriele

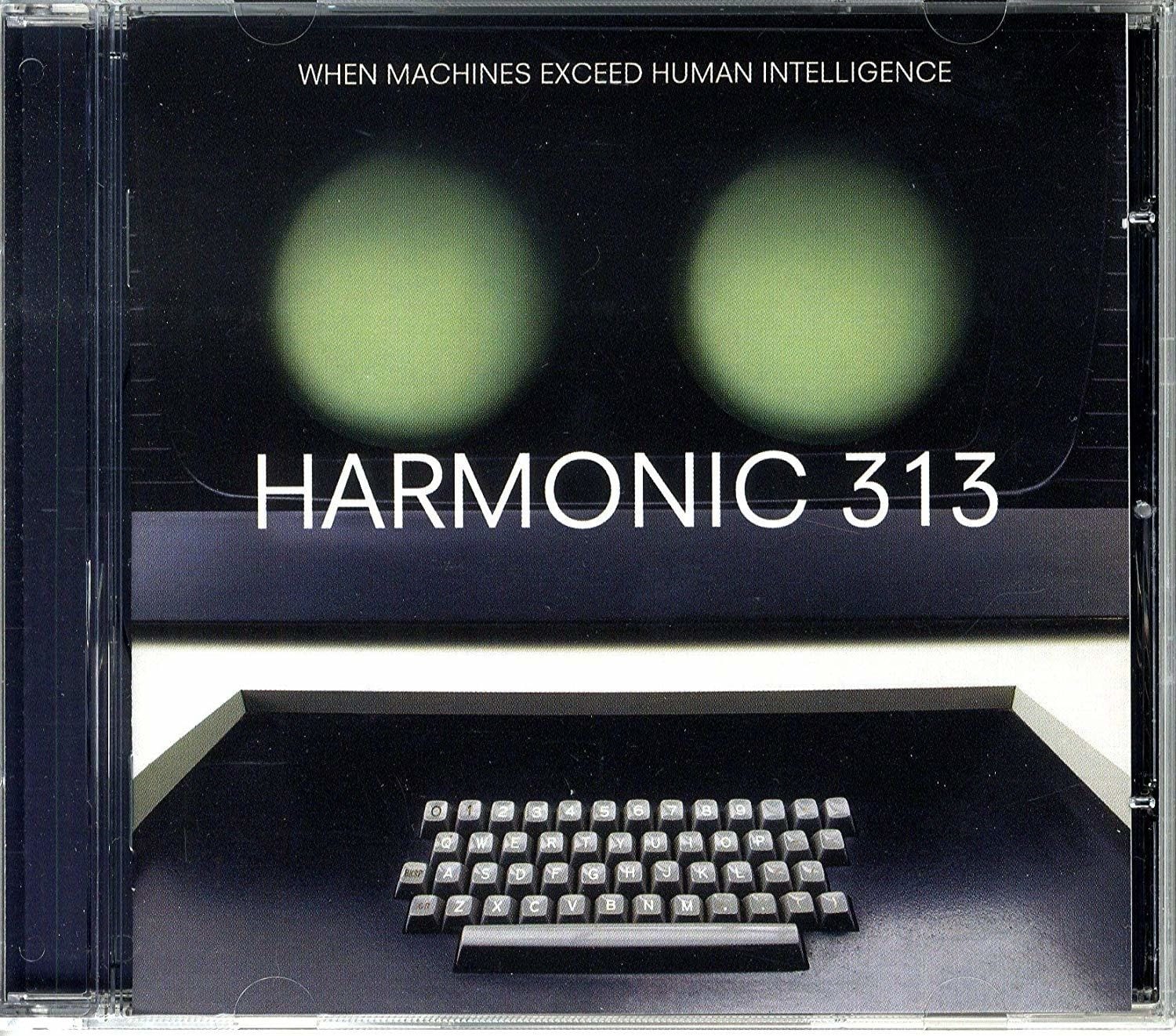

4. Harmonic 313 – When Machines Exceed Human Intelligence [Warp]

Rather than falter under the weight of the grim, future-noir-esque implications suggested by an overt album title, Mark Pritchard’s efforts under his Harmonic 313 guise are astonishing. When Machines Exceed Human Intelligence finds Pritchard dabbling in volatile sonic alchemy, matching gritty and razor-sharp synthesizers against ludicrous bassweight for a techno-and-Total Recall-influenced tribute to Dabrye and J Dilla. A man of many faces (Global Communication, Reload, Jedi Knights, more), Pritchard comes off as a little scatterbrained for inviting Detroit emcees Phat Kat and Elzhi to spit on “Battlestar” (and later, Steve Spacek), but the rest of When Machines boasts such intricate design that a couple of forgettable guest verses matters not. Robust intro track “Dirtbox” surfaced in late 2008 as an appetite-whetting EP, but on When Machines it’s a thunderous, malevolent precursor to the onslaught that follows. Pritchard’s electro hip-hop quivers and quakes on this record, and pondering it again so late in the year has me re-evaluating my 2009 favorites (and 2080 predictions) entirely. – Dominic Umile

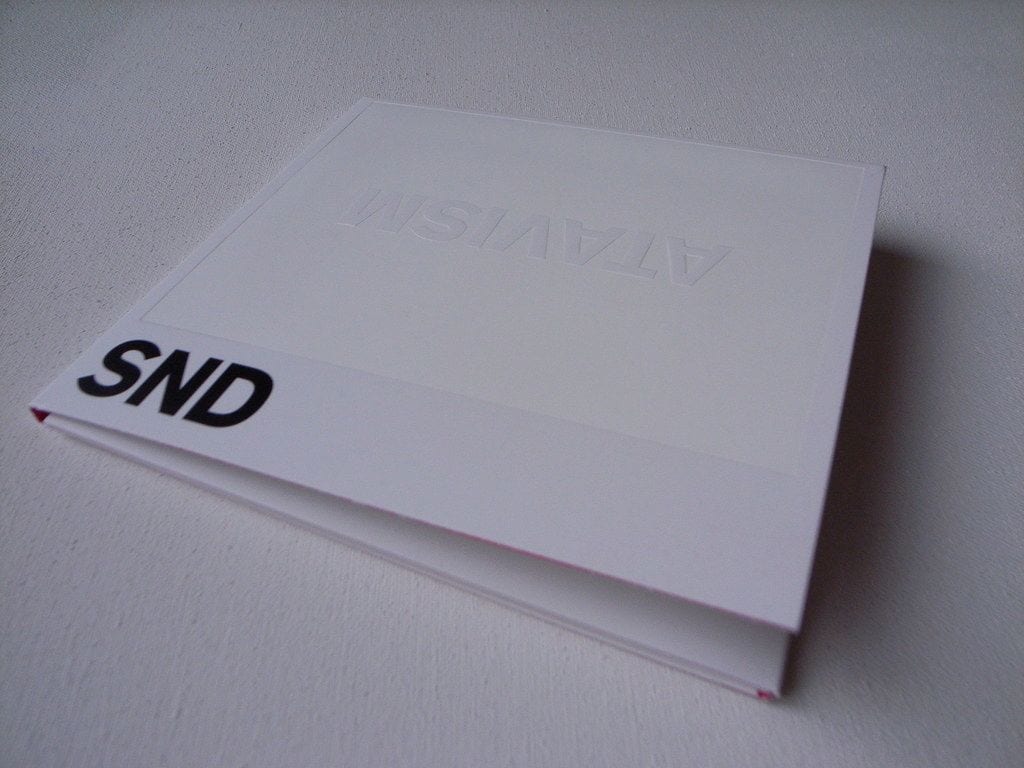

3. SND – Atavism [Raster-Noton]

Okay, I’ll admit it: listen to Atavism enough times, and those sharp digital pads start to sound like the Law & Order “doink doink” sound got a remix job. There’s no caveat of “but wait, come back” with this album. SND are harsh, minimal, sterile, and brutally uncompromising. The sonic palette on Atavism is, compared to other minimal techno records (even its siblings at Raster-Noton), shockingly limited. There are a few percussive sounds, and some (very) slowly morphing synth stabs, all definitely digital. In one fell swoop, SND undo generations of progress toward emulating “analog warmth” on computers, preferring instead to focus on cold processors.

The untitled tracks bleed into one another easily; no one cut has a sonic signature that would greatly distance it from the herd. Fittingly for a comeback, Atavism is, even with its hour-long running time, a statement of purpose that’s free of fat. Fittingly for SND, there’s no grand ceremony behind Atavism. It is what it is, with bare-bones information in a brilliant bone-white package. In his full-length review of the record, M.R. Newmark looked at Atavism as a study in how curiously “safe” computers are. And he’s right — SND is the kind of safe that makes your muscles clench. It’s inexplicable, but it’s also addicting. – David Abravanel

2. Jon Hopkins – Insides [Domino]

Insides was one of 2009’s most pleasant surprises. Before this landmark album, Hopkins seemed content to use his classical piano training to color lengthy ambient soundscapes and easy listening chill compositions. I don’t know if his dog died last Christmas or what, but this album saw Hopkins step into the darkness and invest himself in sweeping, moody melodies underpinned by guttural bass and hints of unforeseen glitch.

Where his previous work seemed content to allow listeners to exist outside the music, Hopkins is incredibly elegant, moving, stirring, and introspective on Insides. It is all foreground listening, percolating IDM tempered with a classical style that allows itself room to breathe. Electronic music so often suffers under the crushing demand for immediate dance floor filler, but this album subtly sucks you into its drama and draws out your deepest reflection and contemplation, while still quenching your thirst for rumbling lower frequencies. Hopkins has now entered the prime of his career with this album. – Alan Ranta

1. FaltyDL – Love Is a Liability [Planet Mu]

As the curtain draws on the first decade of the 2000s, locking it tight within the annals of history, it appears that dubstep has come out on top as the era’s most important electronic movement. It’s strange and maybe a little suspect — dubstep proper didn’t have much to it besides heavy bass and a slow pace, and it produced a lot of copycats whose mission, it seemed, was to zap the life out of UK 2-step and dance music in general. The ones who elevated it to something special were, in fact, those who 86ed most of the rules to pursue a singular ideal; two years ago, Burial’s Untrue hit new levels of bruising emotionality, and suddenly dubstep could make us cry. Now, the best electronic record of 2009 parallels the best electronic record of 2007, using dubstep reference points to build its own stunningly attractive environment in black and silver tendrils around us.

Love Is a Liability, the debut full-length from Brooklynite Drew Lustman, is a foxy world of fashion runways, photographers’ flashes, velvet ropes, and chiaroscuro lighting schemes, a vision of London dubstep refracted off the tiles of a private New York discotheque. It seems like it should have come with a $70 invitation. Milking his oblique production sense and state-of-the-art equipment for everything they’re worth, Lustman explores the peculiar depth in surface-level turn-ons. His computerized sounds exhale diamonds with each sigh (check the gorgeous Cuisinart-in-heaven whirring noises on “The Shape to Come”) and commingle with beat work rivaling 2562 in its poetic fluidity. The vocal snippets from Untrue return, in a sense, but here they burn with sexual energy: A looped “ahh” is spun into silk on “Winter Sole”, and phrases like “I want…” shoot straight for the pleasure receptors and ignite an erotic glow. They could be the ghosts of partygoers from the walls inside the Paradise Garage, coming out for one more dance under the hedonistic spell of FaltyDL’s lights and music. As the legacy of the New York club underground lives on, so may this album. Its most memorable word? “Forever.” When it reverberates through “Human Meadow”, it’s enough to send shivers down the spine. – M.R. Newmark