“What kind of festival is Big Ears?” is a surprisingly difficult question to answer.

Typical festival posters rely on a stimulating visual palette, employing a smattering of font sizes to rank bands by their cultural prominence. Attendees offer more aggregating specificity to these fests through hashtags: #bluegrass, #jazz, and #folk are reasonably paired with #jammin, #party, and #summertimevibes.

Then what to make of Big Ears, where the local paper quoted – with a certain degree of pride – a resident’s disbelief at not knowing any of the more than 100 artists playing the fest? And yet, Big Ears is not a deep dive into the outer reaches of #freakfolk, #EDM, or another #nichecultgenre.

Ten years following its debut – with a few skipped years in the interim – the 2019 version of Big Ears posited that the big in Big Ears is not one of size, but breadth. Each year, this late-March fest showcases a lineup that is big in the sense of encompassing, providing programming with a depth and versatility that rewards adventurous listenership. Knoxville hosts these four later March days in a series of churches, historic theaters, and repurposed aged-wood warehouses that is Tennessee’s cosmic counter-balance to Bonnaroo’s “Great Stage Park”, roughly three hours away in Manchester.

At Big Ears, you are as unlikely to be doused by a stranger’s beer as you are to sing-shout along with a band’s anthemic chorus. These attendees don’t shout song requests – particularly given the unique, rare, and/or intimately immersive nature of these performances. A Big Ears attendee is as likely to passionately pursue what would be an eight-point font footnote artist in the sub-100 capacity Square Room as that of the 28-point headliner in the comfy Tennessee Theatre – a factor Big Ears wholly respects by most-often presenting the artist lineup alphabetically and in homogenized font sizes.

In the magic world of Big Ears, the outer reaches are within reach. It follows that #challenging and even #difficult are not antithetical to #enjoyable at Big Ears. Lessons abound throughout the festival; Big Ears’ subtleties fascinate.

Mid-Friday afternoon, a few hundred attendees crowded on Church Street’s Methodist Church steps until past the scheduled showtime – of concern, as Big Ears’ punctual set times are vastly more predictable than the sets themselves – and occupied each other by gesturing adjectives in an attempt describe Thursday night’s shockingly gregarious Earwig Deluxe set at the small Pilot Light, or the Tennessee Theater‘s sultry ballet Lucy Negro Redux. Streetside levity came in the form of a passing muscle car revving and honking at the assembled mass, when an attendee dryly offered: “Harold Budd fans, obviously….”

Once frisked, most began an uncommonly brisk pace for a religious space so as to secure pews in proximity to the veteran ambient composer, here paired with Knoxville’s own modern music ensemble neif-norf and versatile harpist Mary Lattimore. Yet, as both a mindfulness reset to the audience and a test to their eager patience, the set began with a soloist milking ten minutes of shimmering tones from a gong – with Mr. Budd nowhere in sight. Arriving to applause that was the loudest sound of the next hour, Budd and the ensembles then offered soft and delicate tones that reverberated in competition with the street outside and even the participants themselves.

In and around the pews, the Big Ears ethos asserted quietude. A cameraman was rightfully shushed as his clapping shutter outsized the music; a ringtone next elicited gasps from listeners who had been lost in the mid-air intersection between a vibraphone’s lilting tones and those of Budd’s piano. Attendees scuttling out a bit early to catch Evan Parker’s Trance Map or Roomful of Teeth ensured their soles didn’t too greatly squeak on the church’s shined slate. The set was both a protest against a clamorous culture and an escape from it; noisy outliers were unwelcome and collectively considered rude. Luminous afternoon stained glass light painted those present, who luxuriously adrift and then departed with scant remnant of the prior rush.

Big Ears’ strengths emerge from its well-curated presentation of paradox. These strengths are enhanced by performers who access the uncommon at the fest: uncommon from both popular culture and from the artists’ own standard repertories. Folks at Big Ears know it is special, and travel the world to make their way to and through rural Tennessee to immerse themselves. Perhaps ‘participants’ is therefore more apt than ‘attendees’ here.

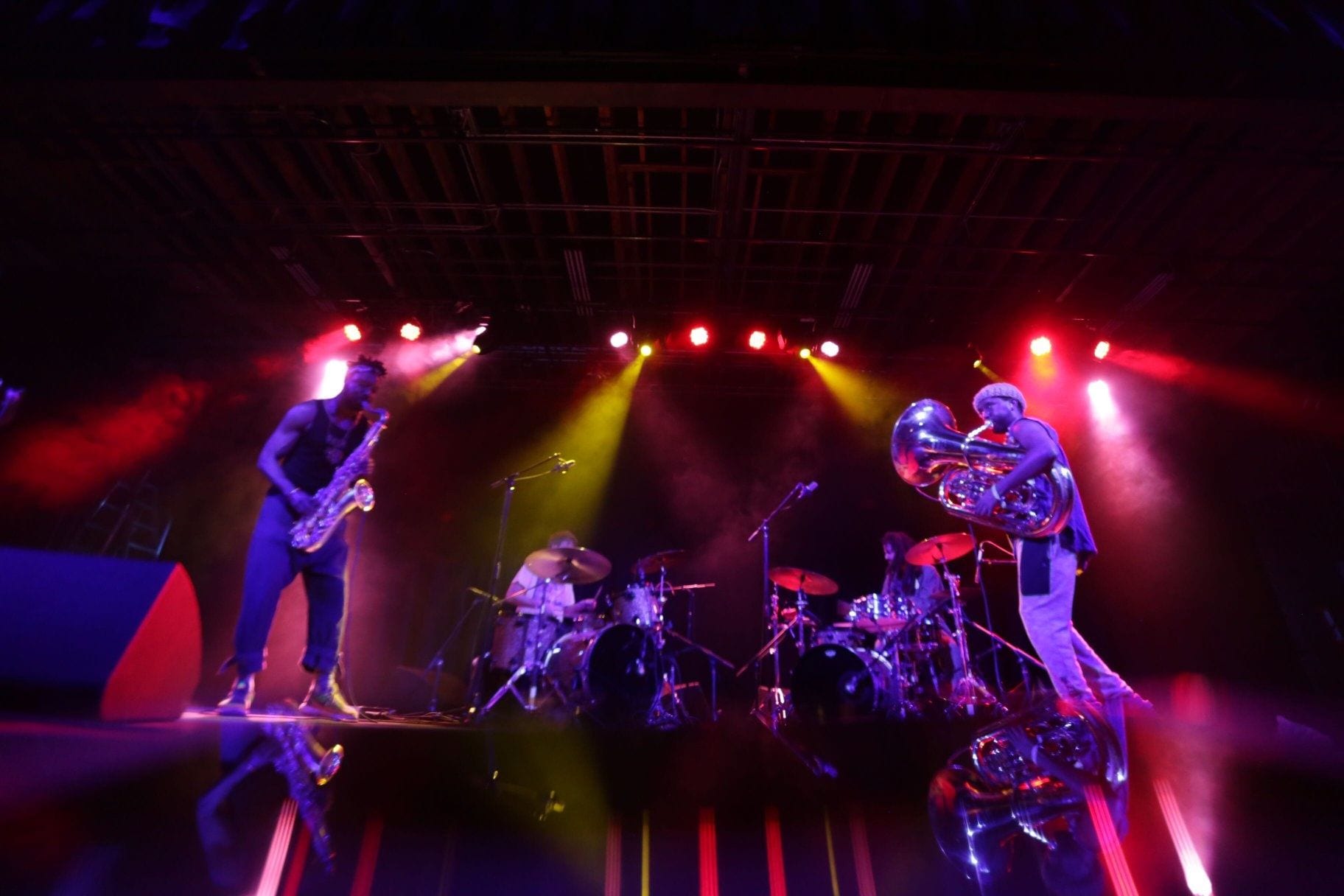

Paradox is subtly manifest. It was in Shabaka Hutchings‘ onstage step-down voltage converter, forgivingly unnoticeable Saturday night beside his saxophone’s amp on a stage which also included two drum sets and an ever-bobbing tuba: Sons of Kemet‘s darkly danceable protest music comes from London via the Barados-born Hutchings, and successfully re-channels the American vernacular of jazz with electrifying currents from genres farther afield. His Comet Is Coming set sadly skimped on sax for synths, thereby losing this reviewer’s interest after the second too-long song.

Arguments over venue selection were certainly possible: most festival attendees were assured that the rococo Tennessee Theater was most appropriate for Mapplethorpe’s unmissable cocks, massive on the silver screen. Most Knoxvillians would presumably prefer they be hidden in a much smaller venue… but then where to put the large vocal ensemble Roomful of Teeth leading a choir singing “America, place your ring on my cock where it belongs.”

No sacrilege was felt by attendees in St. John’s Episcopal at suppertime Saturday, when Amirtha Kidambi helpfully clarified “and I do mean Eat the Rich literally,” before leading her ensemble Elder Ones with vocal gymnastics wordlessly expressing anger and terror, flanked by sax skronk and an equally unsettling rhythm section.

Not everything need be easy or obvious: deep into Friday night, Kara Lis-Coverdale hovered over a laptop, shrouded by static green lights, emitting an hour-long foray starting with sounds akin to an emergency broadcast tone before twisting into woodsy incarnations, surveying what might or might not have been church bells sampled and manipulated. The fact that most attendees couldn’t describe the source, origin, or method of composition didn’t distract from their immersion into hemispheres rocky, unsettling, and transcendent.

Rhiannon Giddens paired with Italian multi-instrumentalist Francesco Turrisi – both of whom scored and accompanied Thursday’s Lucy Negro Redux ballet – in a set whereby an Appalachian fiddle tune paired seamlessly with an Italian tarantella. Mr. Turrisi detailed the history of these “curative trance dances”, whereby one infected by a tarantula bite dances until healed: offering that the “doctor was a drummer, and the nurses are singers” before conjuring his frame drum hypnotically as Ms. Giddens sung circularly in a seemingly spot-on Italian dialect. The duo added a bones player to next present a minstrel-era song, all within an hour that was entertainingly global and startlingly intimate, both a history lesson and one in genre futility. “If you can’t do it here, where can you do it?” quipped Ms. Giddens after explaining that they hadn’t played it safe.

Big Ears 2019 offered one of its most jazz-centric lineups by curating roughly 20 sets celebrating 50 years of cherished label ECM. Of course, the presentations were neither cocktail nor lounge jazz, and showcased that modern jazz can be represented both by Ralph Towner’s acoustic solo guitar forays and by Nik Bartsch, leading the Swiss quartet RONIN that functioned as a minimalist whole while eschewing instrumental solos, lest one member distract from the group’s trance-inducing and rhythmically-shape-shifting bedrock.

“Jazz” is not the first word passersby listening to ECM’s Son of Goldfinger would consider, as they’d more likely be attempting to dissect the instrumentation blaring through wall and foundation – in person, a busy scene where dynamic drummer Chez Smith adds electronic flourishes under David Torn’s guitar and Tim Berne’s horns, conjuring an enjoyably intense paint-splatter of sound. Sunday night culminated with the Art Ensemble of Chicago, where the few remaining original members were aided by Knoxville Symphony and modern poet Moor Mother in a set that surveyed big band cacophony, unsettlingly direct spoken word, environmental atmospherics, and riveting yet discordant swing.

Bill Frisell was scuttling around in different shapes and sounds, playing with Thomas Morgan, the ensembles Absint and Harmony, and accompanying Bill Morrison films with the Mesmerists. He led a Static & Silence session whereby listeners were invited to a morning “experience” advertised as “arrival, the sounds of a bell, silence, music, silence, the sound of a bell, departure” which was held one floor beneath the main festival welcome area: the silence of 80 people punctuated only with creaking wood beams from the record- and merch-buyers above.

Other non-traditional events included workshops, artist talks, and panels whose titles included: Media & New Music; Symposium of Sound: Sound and Spatiality; and What Does the term ‘Experimental’ Mean for Music Anymore, Anyway? Now an annual event, the 12-hour drone “All Night Flight: Dreams of the Whirlwind” happens midnight Saturday until that hour in which church is dismissed on Sunday. At about which time attendees could survey Knoxville’s streets with folk artist Lonnie Holley, who ended with walk by creating a summative found-object sculpture with the participants’ scavenged items.

Big Ears is, well, just that kind of festival. It asks questions, yet it feels no obligation to answer. It shies away genre classification, though there’s an subtly intuitive logic in the curation. One enters Big Ears buying into risk, accepting an invitation to be shown the unknown. While some festivals introduce you to new bands, Big Ears introduces participants to new concepts, to new paradigms. And in a world where the ills seem greater than the remedies, Big Ears is a potent and welcome elixir.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)