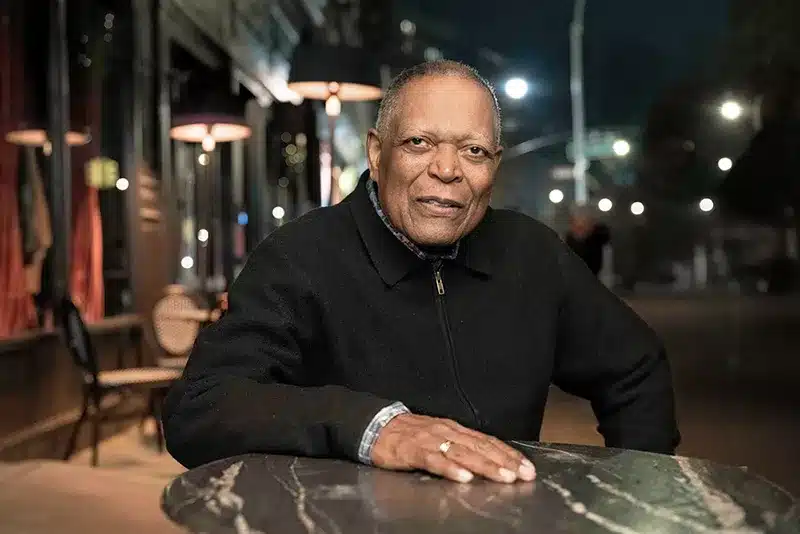

Drummer Billy Hart just turned 85, and what a year for a master musician. His playing on Aaron Parks’ By All Means was subtle and vital; his autobiography (as told to Ethan Iverson), Oceans of Time, was released; and his established quartet has released a new recording, Multidirectional.

The new set catches the band live, playing the John Coltrane standard “Giant Steps” as well as originals from the leader, saxophonist Mark Turner, and pianist Iverson. Ben Street serves in the highly flexible rhythm team on acoustic bass. Hart doesn’t sound like age has dulled him in the least, as he truly commands the band, though he does it as he always has, with a sleight of hand and daring ambiguity.

Billy Hart is from Washington, DC, where he played with a wide range of artists: soul legends (Otis Redding), singers (Shirley Horn, another DC denizen), and jazz legends such as organist Jimmy Smith and guitarist Wes Montgomery. He didn’t head to New York until 1968. At that point, he became an indispensable sideman for the most important artists of that era, including Herbie Hancock, McCoy Tyner, Miles Davis (on On the Corner), Wayne Shorter, Pharaoh Sanders, and Stan Getz.

Then, in 1977 (at the age of 37), Billy Hart released his first album as a leader. Enchance (on A&M Horizon). It was one of the best of the decade, with bold playing and composing from a collision of “inside” and “outside” players, including Dave Holland, Buster Williams, Oliver Lake, Dewey Redman, Marvin Peterson, Eddie Henderson, and Don Pullen. Billy Hart’s relationship with so many incredible musicians put him in a position to consolidate the sound of that moment in time like no other musician.

Recordings as a leader were only occasional. Oshumare (1985), Rah (1987), Amethyst (1993), and Oceans of Time (1997) similarly gathered musicians from across a spectrum (some straight-ahead players, some fusion, some freer players) and spread the composer credits around. It almost seemed that without maintaining a working band, Hart had a musical personality so strong that his various groups all maintained a similar, searching quality. They were not pigeonholed by one style and featured great melodies that invited exploration.

The current quartet came together early in the new century, making its first studio recording, Billy Hart Quartet, in 2005. From the start, this band combined lyricism (particularly in the pure, typically unadorned tenor saxophone playing of Mark Turner), a modern blend of abstraction and classicism (particularly in the playing of pianist Ethan Iverson, who was simultaneously playing in the very different context of the trio the Bad Plus), and grounded jazz history.

Multidirectional shows what the band sounds like today before a New York jazz audience: still lyrical, abstract, and historically grounded but also flowing and free. Billy Hart’s “Song for Balkis” (recorded by the quartet in the studio in 2012) opens the album with mystery and daring: on a beautiful solo for Hart’s toms that gives way to a ballad theme over a rubato time feeling. Hart’s cymbals wash over Turner’s horn, and his toms lift Iverson’s call-and-response lines and chiming chords. Improvisation begins with astonishing playing in the piano’s higher register, not a set of chords moving in time that require a single-note line, but more of a textural, harmonic map of stars against the sky, the tempo absolutely relative.

At first, Hart lightly taps out an accompaniment, then Turner enters as a third voice, followed quickly by Street’s bass. The band improvise collectively, moving from a slow simmer to a gradual fullness, Iverson’s playing gaining power as he is nudged along by drums and bass not bound by a set tempo. What started as delicate and filigreed grows darker, not troubled but clearly much more complex and interesting. The resolution, when it comes, is sweeter for that.

Billy Hart’s “Amethyst” also begins with tuneful percussion and resists locking into tempo. The theme arrives (the title tune from 1993’s Amethyst), but is stated much more loosely. While the solos on the original flow like a pleasing soul ballad, the 2025 quartet keeps time and harmonies loose as can be. If Hart is decidedly influenced by the John Coltrane Quartet, this approach to “Amethyst” is reminiscent of Trane’s later period, when mood and motion predominated over traditional swing and chordal patterns.

The group’s take on Coltrane’s late 1950s ankle-breaker, “Giant Steps”, is transformed similarly. Iverson begins with a mysterious solo piano statement, and Turner enters with only glancing references to the familiar melody, while Iverson lays out. The famously difficult-to-navigate harmonic changes are there, but Turner slides around them in a languorous way. Those waiting for a final statement of melody will be disappointed, and devilishly so.

The two other tracks — Turner’s mid-tempo “Sonnet for Stevie” and Iverson’s slinky ballad “Showdown” — are showcases of this quartet’s sensual groove. “Stevie” gives us Iverson at his most spare and patient, placing his improvised phrases precisely, even when he syncopates left-hand bombs ahead of the beat and melodic phrases just a tiny phase shift behind. Turner’s solo provokes a deeper swing feel from Street, which brings out the prankster in Hart. The leader never breaks the elastic swing, but he sprays the conversation with all manner of tasteful accents and orchestrations which continue into the restatement of Turner’s composed melody.

“Showdown” was on the group’s last album as well, and it’s no surprise that it gets a reprise here (at least on the CD and digital versions of the album). This blue theme is stated with a slight backbeat and an anticipated downbeat every once in a while, which helps give it some grease. Turner is indispensable on this tune. He plays with control and lyricism, but he also gets every chance to find delicious blue notes and tug on them in the slightest way. It’s a dream of a performance.

The title of Multidirectional comes from Hart’s conversations with Coltrane late in his career, when Trane was working with drummer Rashid Ali. The recently passed drummer Jack DeJohnette used this word as well. The idea is that jazz rhythms are contrapuntal and polyrhythmic, having simultaneous and shifting directions and crosscurrents.

That word applies not just to Billy Hart’s drumming but also to this quartet, which can organize its music variously, playing free and funky or both at once, unafraid to sound like it is reshuffling itself and its music over decades, a single album, or even a single track. Multidirectional is distinctive and exemplary modern jazz from a master bandleader who rarely makes a false move. This album is on the money.