The story of Bob Marley‘s Catch a Fire, released a half-century ago, is a familiar tale of appropriation and popularization of the local gone global. It’s the moment a popular singles band in Kingston transformed into the vehicle of Marley’s ascent to superstardom and reggae’s assimilation into the melting pot of global pop music. I have no idea how it felt from ground zero in Jamaica—novelist and Kingston native Marlon James tells it several ways, including this one, attributed to Marley by a local gangster: “The Singer tell me a story. How back when reggae was something only few people know, how white rock and roll star was him friend. … They like him better when he was the poor cousin that they can feel good for taking notice.”

From 1972 through to his untimely death in 1981, Marley and the Wailers were at the fulcrum of geopolitical forces, widening inequality and instability, seismic shifts in the marketing and distribution of popular music, and an explosion of creativity driven by brilliant, headstrong, and conflicted individuals. Pressure drop, indeed. Jamaican-born dub poet and activist Linton Kwesi Johnson neatly sums up the paradox of Marley’s meteoric rise without trying to reconcile his appalled reaction in 1975 and his reassessment over forty years later: “The astute and at times obscene marketing of Marley as a brand cannot detract from the fact that no other recording artist in the late twentieth century, in any genre, has had the global reach and influence that Marley has, continuing into this millennium.”[1]

It’s a story that’s been told many times, perhaps most effectively in Brooklyn-born reggae archivist and former Island Records producer Roger Steffens’s oral history So Much to Say, precisely because he allows the myriad of conflicting eyewitness accounts to sit next to each other on the page as so many stories, all of them relevant, none of them definitive. I promise I’ll get to that story, but I need to set the scene to do so. Because the scene, back then, and the sense of scarcity at its core, wherever you were, was local in a way that has long since vanished in the rearview mirror of our streaming life. In hindsight, it’s so easy to imagine that the album dropped, and that was that, and so easy to forget that it didn’t work that way.

So my version of Catch a Fire and the Marley story is not only about the landmark of its existence but the long, slow process that was its global reception on the ground. And the only way to tell it, back then, is from where I came in. After all, as a soon-to-be “white college kid”, I was precisely the target audience media mogul Chris Blackwell had identified as the key to the Wailers’ crossover success.[2] Indeed, on their first US tour in 1973, they’d been fired by headliners Sly and the Family Stone after only five dates.[3]

So, it’s around 1980. I’m nearing the end of high school in Kentucky. My copy of the Wailers’ Catch a Fire is dubbed onto side A of a 90-minute Memorex cassette tape. I remember side A down to the color and style of my handwritten credits. But when I sat down to write this essay, I couldn’t remember what I had copied onto the flip side, so I went to check and discovered I must have lent the tape at some point to someone who had never returned it. That was the way of things from 1973, when the album was released, until around 1980, when my music friend John Bailey lent me his copy of Catch a Fire, and on to whenever it was in the 1990s that we switched over to CD-ROM and then flash drive and then just gave up owning and moved online.

John and I had met because we were the only people a mutual friend knew who listened to the Velvet Underground—and, yes, unlike me, John was indeed one of those proverbial listeners who had gone on to start their own band. We exchanged and taped each other’s records, or at least I taped his; John’s band was hardcore punk, and my treasured copies of Loaded (scored on a school trip to Chicago) and Paris 1919 (from a cache of treasures at a used record store in San Francisco found traveling after high school) were, he said, too soft and mellow for his exacting ear. Like the Velvet Underground & Nico, though, Catch a Fire met his high-art-punk and high-school-punk standards.

John and I lost touch when I moved away from Louisville for good after finishing college. Orange-Orange released a 45; the renamed Your Food released their classic debut long player Poke It With a Stick (1983). This one I never lent, and it’s still at home with me. Poke It was reissued on Green Noise in 2018 and is now streaming digitally everywhere. Your Food’s bassist Wolf Knapp went on in 1985 to form the great indie band Antietam with members of the Babylon Dance Band, another notable Louisville new wave/post-punk band from the early 1980s. Along with Catherine Irwin, then of the Dickbrains and later to form alt-country duo Freakwater with Janet Bean, they all hung out at the “punk house” on Bardstown Road, a few blocks down from Karma Records and Pyramid Records, where over the years I sourced the more mainstream parts of my used record collection. But neither the Velvet Underground nor Catch a Fire was the sort of album to turn up used in Louisville record bins. This was scarcity: the only way to hear either one, if you didn’t live in New York or maybe the West Coast, was through the grapevine.

In Louisville, you took what you could find and were desperate for more. Like Marley and the other Wailers in postwar but not yet postcolonial Jamaica, we grew up on top-40 AM radio (ours was WAKY – pronounced as if it has a “c” in front of the “k” – yes, really) before graduating to the now numbingly familiar but then intermittently thrilling album-oriented rock of WLRS. There wasn’t much else to hand unless you hunted it down out of town, borrowed it from someone else that had, or made it yourself. As a result, I had a lot of music friends—the guy who only liked Traffic; the brothers who would have long conversations about which songs to skip to squeeze both Specials albums and the EP onto a single 90-minute cassette; the housesitting friend I convinced to let me borrow Aretha’s Young, Gifted and Black for a day to copy at home (yes, I returned it as promised), and who didn’t understand why I wanted it since she was only into New Order 12-inch singles (“Temptation” and “Blue Monday”, mostly) and, for some obscure reason Godley & Creme; the woman at the punk house who sold me her full run of Daevid Allen and Gong records for a budget price. As reggae went, there was the soundtrack to The Harder They Come (1972) and the two Bob Marley & the Wailers live albums, then known simply as Live! (Lyceum, London, 1975) and Babylon by Bus (mostly Paris, 1977). None of us would have admitted it—what could be less authentic than getting your musical tastes from a guidebook—but we were probably all memorizing the Rolling Stone Record Guide (certainly I was), which was first published in 1979 and clued those of us in the boondocks into what we had all been missing and what to look out for at record stores when we were on the road.

The Velvet Underground & Nico is predictable and explicable in this story of influence; Catch a Fire may not be surprising, but neither can I easily account for what exactly it was about it that met John’s—or many another young punk’s—exacting standards. Reggae had punk cachet in the late 1970s. Before Catch a Fire, I had found an LP of The Harder They Come (popular enough to be released throughout the decade) and had dubbed cassettes of the Marley live albums from my older sister, who had her own music friends from college. Along with the UK ska revival, or two-tone, led by the Specials, I was, like John, waist-deep into the Clash, who had been onto reggae from the sped-up and stretched-out cover of Junior Murvin’s “Police and Thieves” on their debut album.

The Clash lived in London, after all, and considered Notting Hill, then the spiritual, cultural, and political center of the Black Caribbean diaspora, their home base. Their Lee Perry-produced single “Complete Control” and the reggaefied critique of reggae pop in “White Man in Hammersmith Palais” were on my cassette of the 1979 US version of the debut album, the only one we knew back then in Kentucky (although I can’t remember who I borrowed it from—must have been John). In Philadelphia for college, I had picked up a copy of the ten-inch (a gimmick from Epic records) compilation Black Market Clash, with its sped-up cover of Toots and the Maytals’ “Pressure Drop”, stoned tempo cover of Willie Williams’s “Armagideon Time”, and the Strummer/Jones/Mikey Dread original “Bankrobber/Robber Dub”. So, like John, I knew that reggae had the punk seal of approval.

What I didn’t know at the time, because my knowledge of the Grateful Dead in the 1970s did not extend much beyond American Beauty, and I somehow didn’t even hear Eric Clapton’s “I Shot the Sheriff” or Johnny Nash’s “I Can See Clearly Now” as reggae, was that reggae wasn’t just a punk thing. Whether attracted to the outlaw ‘rude boy’ reputation or the music, or both, the Jerry Garcia Band was performing songs from The Harder They Come and Catch a Fire during live shows from as early as 1973. Not that this would have mattered much to John. But in retrospect, it tells me how much and in how many ways reggae cut across genres and forms by the late 1970s, from punk to the Dead. And not so much in the way Bob Marley would do later when he went global as a pop-rock star, a process that had already started with Clapton’s 1973 cover of I Shot the Sheriff, which even played on WLRS, and which we just knew as an Eric Clapton song. (I didn’t know then that Clapton had travestied his reggae connection in 1976 with an onstage racist anti-immigration tirade.) But as something that sounded to ears like ours both impossibly new and strangely familiar, something that took what we had grown up with on the radio and the turntable and flipped it around into something we’d genuinely never heard before.

Those two live albums still have a special place in my heart, and I played them so often—far more than Catch a Fire, to be honest—that they’re also engraved in my brain forever, groove for groove, propulsive and urgent with every so often a breath taken for pure joy. Pure joy always led me to prefer Babylon to Live!, despite the RSRG canon. Good white American that I was, this was how I wanted my politics and anger: bookended by, if not fully interwoven with, the transcendent pop of “Positive Vibration” and “Jamming”. Catch a Fire has that same vibe. Much later, I discovered that this vibe was also part of the Lyceum shows the Live! LP had been culled from where the Wailers performed “Slave Driver”, “Kinky Reggae”, and “Stir It Up”, alongside what, for me, remain the canonical seven tracks on the original Live! LP. Similarly, a sunny “Stir It Up” and “No More Trouble” were the only album tracks to make it onto Babylon by Bus. Both versions sped up the originals on Catch a Fire.

What was so important about this album, I think, was what so many originalist critics have since taken it to task for. Burning Spear were too heavy and raw to cross over; Toots and the Maytals too Black and R&B; and The Harder They Come, a compilation mixing Cliff’s originals with earlier classics. Catch a Fire found the sweet spot between reggae, punk, and rock, and Bob Marley blew up out of that sweet spot into the stratosphere of global stardom. What’s fantastic about Catch a Fire is that you can still hear ‘authentic’ Kingston reggae hybridized with what would become the pure pop nectar immortalized the middle of the following decade in Legend. That doesn’t mean I don’t love Winston Rodney and Toots Hibbert, just that they’re doing something very different from Bob Marley, and I have no need or desire to reduce all roots reggae to a single criterion.

I’ve never had much truck with the authenticity obsession of music buffs, anyway. Given that the Wailers covered American pop from their earliest days; that as Marley’s wife Rita put it of the early days in Rebel Music: The Bob Marley Story (2001), “They were going to be like The Impressions. Because that’s all they listened to most of the time … Curtis Mayfield. James Brown”; that Marley had spent most of 1966 living with his mother in Delaware working to earn money for the band, listening to songs like “Eleanor Rigby”, and experiencing the Black Power movement firsthand[4]; and that when Marley set up Tuff Gong and began releasing his own records, he continued to blend pop, politics, and roots reggae, it seems far more to me that Marley and the Wailers were engaged from the beginning in an ongoing give-and-take between the localized rhythms of the Kingston sound systems and the Anglophone pop world. Sure, there were market forces and exploitative record producers at work. But there were also the active choices and agency by genius musicians who knew what they wanted and weren’t overly concerned with authenticity, purity, or genres. Nor should they have been; they had the ultimate credibility of having lived the lives and hardship. They continued to document even as they also sang of the faith and community that got them through.

The standard story of Catch a Fire is that Chris Blackwell diluted the authentic force of the Jamaican master tapes to make them more accessible to a primarily white, rock-based audience, bringing in white, rock-based, American keyboardist John “Rabbit” Bundrick and guitarist Wayne Perkins for overdubs in Island’s London studio. There’s no question he changed them. London-born and Jamaica-raised white son of an English heir and a Sephardic Jew from Costa Rica, Blackwell founded Island Records in 1959 primarily to distribute Jamaican singles to the diaspora in the UK. Island was also the home of prog rockers King Crimson, Jethro Tull, and Traffic, and folk-rockers Fairport Convention, Nick Drake, and Cat Stevens. Blackwell was no purist; Fairport had made folk rooted in archives and blown up with rock instruments and arrangements, while the Crimsons were sui generis. Just that short list shows he had an extraordinary eye both for talent and for boundary-pushing genius with a knack for making money off of music. Blackwell’s goal with Catch a Fire, he recalls in Rebel Music, was “to present them as like a Black rock group”. It’s worth noting that in 1973 there was nothing obvious about Blackwell’s boundary-pushing strategy; “Black rock group” was an oxymoron back then. In many eyes, bafflingly, it still is.

That white musicians have always sourced their ideas from Black forms has long been a truism. In the early 1970s, the go-to Black form was reggae (former Cream and Blind Faith drummer Ginger Baker’s studio in Lagos and early 1970s collaborations with Fela Kuti notwithstanding). As Rolling Stone journalist Michael Thomas wrote in a sensationalized but highly detailed report from Jamaica’s Dynamic Sounds recording studio, “That’s where the Stones [Goat’s Head Soup] and Cat Stevens [Foreigner] and Elton John [abortive sessions for Goodbye Yellow Brick Road] and Leon Russell and all the other bright sparks from England and America have been working lately; it’s where Paul Simon cut ‘Mother and Child Reunion.’” (It’s also one of the studios where Catch a Fire was recorded in the latter half of 1972.)

Houston native Johnny Nash had been based in Kingston since 1965, publishing music, cutting records, and collaborating with Marley and others. The big record companies were moving in, primed to take the scene global: “Warner Brothers records is moving in and pumping money into the scene. They’ve signed Jackie Edwards and Ernie Smith and the Maytals, as well as Jimmy Cliff. Over in the big pink mansion house on Hope Road, Island is putting cash in advance into the Wailers; Bob Marley has the run of the place.” As Marley’s childhood friend Segree Wesley, who was on the first US tour, remembers explaining to Bunny Wailer, “I’m in America—you’d be surprised to know how they accept the reggae. As a matter of fact, the white folks accept reggae more so than the black folks right in America.”[5]

What happened to reggae in the Black US was rap, which was born in the Bronx in the early 1970s out of the dub-heavy sound systems of Jamaicans like DJ Herc (Clive Campbell), whose families had fled the violence of their home country.[6] That’s a different story, but it does suggest Blackwell and Marley had the right instinct about the route for crossover success. Yes, the unrelenting heaviness of the Jamaican version of “Slave Driver” almost literally outweighs the gussied-up Island version. But it’s not so pronounced on other songs. While the bass is far heavier on the original “No More Trouble”, the added keyboard and guitar loops heighten the ominous tone of the album version in compensation. (Both versions can be heard, along with two songs omitted from the Island album, on the “Deluxe” version released in 2001, also the last time Catch a Fire was reviewed in PopMatters). Marley and Peter Tosh (who wrote and sang lead on “Stop That Train” and “400 Years”) didn’t just write striking and evocative lyrics; they also wrote gorgeous melodies and irresistible hooks. Even their most political songs burrow into the brain as earworms. Just try to forget the ominous, driving intro of “Concrete Jungle” or the gospel-inflected chorus of “No More Trouble” once you’ve heard them. Lyrically, too, both songs balance harsh social critique with Marley’s trademark Rastafari (if not also Beatles-) derived need for “love.”

Bunny Wailer left the band before the 1973 US tour. Peter Tosh followed not long after, for reasons both patent—they didn’t like Blackwell or the direction he or Marley was taking the group—and opaque because so many versions are around. Of course, neither of Wailer nor Tosh was a stranger to the circulation of US and British pop/rock forms, either. In their early days recording for Coxson Dodd, they had covered Tom Jones, Dion and the Belmonts, and the Beatles. Tosh first recorded the Temptations’ 1965 R&B hit “Don’t Look Back” in 1966 for Coxson Records as a ska cover. When he returned to the song for his 1978 solo album Bush Doctor, the chart-topping single featured Mick Jagger on vocals and an upbeat saxophone solo from band member Luther François, “the godfather of jazz in St. Lucia“. The influence was not unidirectional, in other words, and the Wailers weren’t the only reggae artists who were well-versed in American and British music and determined to bend it to the service of their careers and their musical visions.

New Jersey native (and rock and jazz band alumnus) Al Anderson’s guitar solos—heavily filtered on “Rebel Music (3 O’Clock Roadblock)” and lyrical on “No Woman No Cry” at the Lyceum concert; blistering on “Heathen” in Paris—or Tyrone Downie’s keyboard stylings on the Lyceum’s “Stir It Up” indicate the shift to a hybrid reggae rhythm, lyrics, and attitude with rock’s breaks and bridges. They also remind us that Black musicians know as well as whites how to rock out. Critic Dave Marsh may have dismissed this shift in the RSRG as “guitar-noodling” and “superstar guitar” (in the misguided assumption that Marley, rather than Anderson, was the guitar hero).

Robert Christgau came closer when he assessed the final stage of this shift in Legend (1984) as a testimony to a “popcraft, which places Marley in the pantheon between James Brown and Stevie Wonder”. That popcraft was as rooted in reggae beats as it was in rock structures. A listen to Babylon by Bus‘ “Heathen” or a watch of the moodier Rainbow recording, also from 1977, reveal the Barrett brothers (Aston ‘Family Man’ on bass and Carlton ‘Carly’ on drums) to remain as heavy in the mix as Anderson’s Jimi Hendrix and Eddie Hazel-ish licks. In its policing of Black authenticity, Rolling Stone’s critics equally worked to police the whiteness of rock music, belying genre hybridization where it was happening and effectively reinforcing ghettoization overall.

Pop covers had always been part of Jamaican music. While ska, rocksteady, and reggae covers typically indigenized American and British hits away from choruses and bridges and into groove-heavy dynamics, these indigenized songs seldom traveled beyond Jamaica or its diasporas, especially in England. When covers or originals did cross over, like Desmond Dekker’s 1968 smash hit “Israelites“, they did so more as novelties than as the star-making breakthrough Marley and, to a lesser degree, Tosh, found through rock hybrids in the late 1970s. Until the rise of hip-hop, Black music had always been softened to crossover to white audiences, when it wasn’t simply appropriated instead.

That was Johnny Nash’s recipe in 1972 for the #1 single “I Can See Clearly Now” and the top 20 cover of Marley’s “Stir It Up”—so mainstreamed they don’t even need to be heard as reggae. Rock music offered an alternate route because hard rock fans used an opposite logic to Tin Pan Alley. At least back then, they would only embrace ballads and love songs when persuaded they didn’t betray the genre’s credo of ‘hardness’. The more rough edges with the hooks, the better. Still, reggae had mostly offered early 1970s pop-rock stars a new flavor like disco would a few years later.

But reggae turned out to mean a lot more a few years later to punk artists confined to the strictly limited diet of 1977’s ban on anything resembling popular music of the past. It offered an escape route that was resistant to accusations of selling out. Like the rockabilly and outlaw country the Clash also returned to in 1979, the Wailers had strong “rude boy” credibility to go with their musical chops. Nor were the Wailers themselves unfamiliar with outlaw country, either. According to Bunny Wailer on the 1973 single “I Shot the Sheriff”, that would break them out through Clapton’s 1974 cover: “From the start it was intended to have that kind of cowboy ballad vibes, like Marty Robbins.”[7] And, as filmmaker and so-called “white Wailer” Lee Jaffe noted, likely also remembering a famous scene in The Harder They Come, the song “came out of western movies, which Jamaicans really love. The Good, The Bad and the Ugly was always playing somewhere in Kingston.”[8]

The Wailers’ combination of what Christgau terms, approvingly, “hooky chants” with low-end groove and unapologetically radical lyrics provided a seductive musical correlative of Joe Strummer’s lyrics for the Clash’s first single “White Riot“, penned following Black Britons’ battle with police during the 1976 Notting Hill Carnival. Bemoaning how “White people go to school / where they teach you how to be thick” while Black people “got a lotta problems / But they don’t mind throwin’ a brick,” Strummer urged whites to emulate what he saw as Black radicalism and resistance. That song, of course, had as brutal and short a punk sound as the Clash ever displayed. Its lyric was both iconic enough and misunderstood enough as a white nationalist message that it made the natural title for documentarist Rubika Shah’s 2019 film about Rock against Racism, White Riot. They were no newcomers to reggae, either. Bassist Paul Simenon had been living in Notting Hill since 1970, falling for reggae early on. Strummer had played his first professional gig in 1974 with the 101ers, opening for London reggae artists Matumbi in Brixton.[9] The two bands would later share the stage at the landmark Rock against Racism rally in Victoria Park in 1978.[10]

All four members of the Clash had been required to eschew their musical roots (not to mention their more-or-less middle-class backgrounds) in deference to the scorched earth ethos of early punk music. But as Marcus Gray exhaustively documents in Route 19 Revisited, reggae unlocked the musical equivalent of that same gesture in London Calling. Following a disappointing attempt to make themselves over as a hard rock band (Give ’Em Enough Rope), The Clash instead were able to open up the punk ethos to the musical forms they had grown up with (jazz, rockabilly, pop, ska) and those surrounding them (reggae and dub). Consequently, like Marley, around the same time, they were able to expand their local following globally without sacrificing their musical or political principles. Although with far less commercial impact but plenty of later influence, Matumbi’s frontman Dennis Lovell similarly helped form a hybrid framework while producing the all-female punk band the Slits‘ 1979 debut, Cut. Public Image Ltd.’s post-punk landmark Metal Box (1979) was equally dub-drenched.

Following an assassination attempt at his home compound in Kingston, Marley was living in self-imposed exile in London from 1976 until 1978. It was here that he wrote “Punky Reggae Party” as a response to the Clash cover of “Police and Thieves”. He’d been introduced to the track by journalist and post-punk musician Vivien Goldman, the daughter of German-Jewish refugees, although Black filmmaker, DJ, and musician Don Letts attributes the song to a conversation sparked by the “bondage trousers” he was wearing the first time he met Marley in 1976.[11] Like the multiracial alliance Rock against Racism or the multiracial bands of the ska revival (multigender also, in the case of the Selecter, fronted by Jewish-Nigerian Essex native Pauline Black), Marley’s song called for a “joyful sound” that would also inject “reality” into a dominant “world of hypocrisy.” There was little joy in evidence in the first two Clash albums or most other first-wave punk; however, it’s there in spades on London Calling as also on The Cut, The Specials, the English Beat’s Just Can’t Stop It, the Selecter’s Too Much Pressure, and with no evident diminishment of the dose of reality they all brought to the world of British (not to mention American) pop music.

In this context, Marley’s rocked-out reggae-pop simply returned the favor, absorbing the multitude of styles and approaches throughout the 1970s without ever fully abandoning the rocksteady beat, the Rasta ethos, or the bedrock dedication to social justice and coalitional politics. The latter wasn’t unprecedented in Black American music—very likely Marley drew on the inner-city dramas, biting critique, and explicit activism of Curtis Mayfield’s first few solo albums, Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On (1971), or early Funkadelic, among other American artists—but they were pretty absent in 1973 from white-dominated rock ‘n’ roll. I can’t think of anything in rock from before punk that is comparable in lyrical impact to album opener “Concrete Jungle”. The image itself was nothing new; what was new was the historical continuum in which Marley grounded the lyric: “No chains around my feet but I’m not free / I know I am bound here in captivity.” That these lyrics come after a swirling keyboard opening underpinned by the closest thing on the album to a driving rock beat makes their argument all the more effective. That is, the new arrangement suggests, this song has meaning not only in the local context of Trenchtown but in geopolitics circulating on the same global scale as rock music. Put another way, rock is not outside of this history but implicated in and through it.

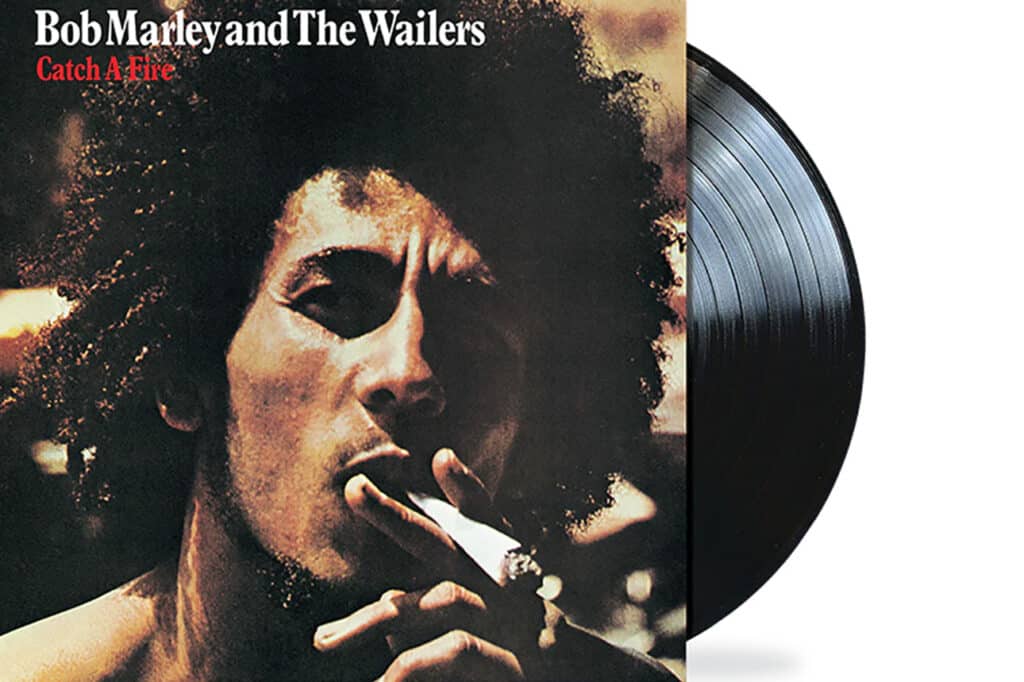

The original album art had cleverly updated the title image in “Slave Driver” to argue implicitly that the warning about violence and rebellion in the past: “Catch a fire / So you can get burned now.” Marley had not forgotten the Black urban radicalism of his years in the US or the civil rights demands and history of enslavement underlying it. When the record design proved unwieldy and expensive, the iconic spliff-bearing portrait of Marley replaced it in 1974. Both versions suit the album. However, as critic Jason Mendelsohn observed in a 2013 conversation about Catch a Fire, the photo “only serves to misconstrue to intended message of the phrase ‘Catch a Fire’, which roughly translates to ‘cause trouble’—more akin to calling for civil disobedience than getting high”. I’m pretty sure the call is more for what Strummer calls a riot and what Marley’s final studio album called Uprising than for “civil disobedience”. Still, it’s hard to imagine anyone listening to the first three songs in Blackwell’s sequence—“Concrete Jungle”, “Slave Driver”, “400 Years”—and not get the point. After those three, “Stop That Train” comes as a respite while side A closer, “Baby We’ve Got a Date”, feels irrelevantly lightweight. Compare this side to the Jamaican sequence, where “Concrete Jungle” is followed by “Stir It Up”, the spiritual love song “High Tide or Low Tide”, and “Stop That Train” before getting back to “400 Years”.

If you want to skip the politics and start with side B opener and all-time classic “Stir It Up”, you’ll also get the explicitly sexual “Kinky Reggae”, followed by “No More Trouble”, a sequel to the three openers on side A, closed by “Midnight Ravers”, which appears to reject the sexual openness embraced in “Kinky Reggae”. For me, both “Stir It Up” and “No More Trouble”—great songs already—benefit further from Blackwell’s touches. The filtered guitar on “Stir It Up” pulls it out of its Jamaican context, similarly to the overdubs on “Concrete Jungle”, while also reminding us (as opposed to “Baby We’ve Got a Date”) that sexual metaphors allow great pop-rock songs to have political connotations even if they’re obviously first and foremost about getting it on. On “No More Trouble”, the haunting piano and guitar opener harks back to similar openings in “Concrete Jungle” and “400 Years”, recalling the politicized opening and again linking the present (“we don’t need no more trouble”) with the long history that has preceded it.

The album format, critic Eric Klinger notes, was not previously integral to reggae, which had been a singles-based form. The LP design and the careful sequencing both helped to signal Catch a Fire as a bonafide album of thematically linked songs. And you could argue that the way “No More Trouble” brings together the outside world with the inside (“what we need is love”) means they’re of a piece in Marley’s worldview. That cohesion was made even clearer when Marley spliced “No More Trouble” with the 1976 track “War”, based on a 1962 speech against racialized inequity to the United Nations by Ethiopian emperor and messiah for many Rastafari, Haile Selassie, for his 1977 tour. When you preface it with a song explaining its many conditions (“Until that day / The dream of lasting peace, / The world citizenship / The rule of international morality / Will remain in but a fleeting illusion to be pursued, / But never attained, / Well everywhere is war, war”), the call for “love” takes on a very different meaning. The political and the love songs on Catch a Fire make a lot more sense together. That’s something Black music, from the blues to jazz to R&B, soul, and funk, have known and done forever, but it’s something white rock music, not to mention punk, really needed.

It’s something the punks took to heart as they created what would much later be viewed as the initial salvos of post-punk, from London Calling and Sandinista! to Gang of Four, the Mekons, and others in the UK, Bad Brains, X, and others in the States, or Aterciopelados in Colombia, Café Tacuba in Mexico, and so on. Listening another time to Poke It with a Stick, I had not noticed before how prominent Wolf’s bass is in the mix and how much it leads into and drives the songs. I notice how songs like “Cool/Cowtown” are both punk and post-punk, or even about the relationship between them. But I don’t hear much else of Catch a Fire in it; the album feels pure Louisville, in some ways, I love and in others, not so much.

As for the Wailers album John and I shared, still today, I feel how true it is to itself even as it’s pushing at its own constraints and bursting out from what reggae was allowed to do. Music for me is always bound to the times, places, and people I first heard it in and with, so the Wailers’ Catch a Fire for me is not only its release 50 years ago and what happened during the seven or so years before I first came upon it in the middle of the punk and post-punk it helped to authorize. That also helps me to keep it separate from either the feel-good, dance floor Marley I was soon to encounter in college (and to which I still prefer the rock hybrid of Catch a Fire and the intensity of the live albums), or the life’s soundtrack Legend would become in the 1980s, incomplete but impossible not to love. The boundary-crossing this album did still opens my ears and pisses me off all these decades later, solos included.

WORKS CITED

[1] Linton Kwesi Johnson, “Introduction: The People Speak,” in Roger Steffens, So Much to Say: The Oral History of Bob Marley (New York: Norton, 2017), 15.

[2] Blackwell in Steffens, So Much to Say, 150.

[3] Reggae musician and tour member Joe Higgs in Steffens, So Much to Say, 150.

[4] Vision Walker, in Steffens, 86, and Steffens, 78.

[5] Segree Wesley, in Steffens, 172.

[6] Jeff Chang, Can’t Stop Won’t Stop: A History of the Hip-Hop Generation (New York: St. Martin’s, 2005).

[7] In Steffens, 161.

[8] Lee Jaffe, in Steffens, 162.

[9] Marcus Gray, Route 19 Revisited: The Clash and London Calling (Berkeley: Soft Skull Press, 2010), 352.

[10] For more on this show and on Rock against Racism, see White Riot.

[11] In No Fun, ep. 8 of Dancing in the Street: a Rock and Roll History, PBS/BBC, 1995.