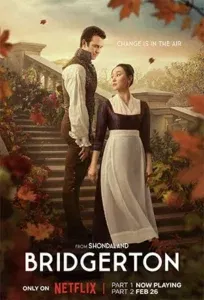

Bridgerton, directed by Chris Van Dusen and produced by Shonda Rhimes, first aired on Netflix in December 2020 and released its fourth season in January 2026. The series is an alternative-history romance drama that centers on the influential Bridgerton family and the romantic lives of its siblings in London’s Regency-era high society. The show is based on Julia Quinn’s novel series of the same name, and one of its most distinctive features is its “racially” diverse casting.

At first glance, this diversity may seem like a progressive intervention. However, Bridgerton conveys a deeply problematic colonial message. The series perpetuates what scholars describe as coloniality—the enduring patterns of power, knowledge, and representation that persist after formal colonialism—by subtly embedding these ideas in the viewer’s consciousness.

Bridgerton has not escaped criticism. The show has been accused of “woke casting”, with some arguing that its emphasis on representation feels excessive or superficial. Others, such as Aja Romano writing for Vox, have highlighted the underdevelopment of characters of colour compared to White characters, undermining claims of genuine progressivism. Additional critiques raise concerns about the trivialisation of the lived realities and historical struggles of people of colour during the Regency era.

Given that Bridgerton is explicitly a work of fiction set in an alternative historical universe, criticisms related solely to historical inaccuracy or the inclusion of racial minorities are, to some extent, digestible. The more significant issue lies elsewhere. The core problem is not the presence of people of colour, but how they are represented.

At its core, Bridgerton operates on the assumption that race and ethnicity can be reduced to skin colour alone. By detaching race from histories of colonial violence, cultural identity, distinct ways of being and knowing, and structural inequality, the series promotes a narrow and depoliticised understanding of racial justice.

In this imagined world, racial inequality appears to be resolved simply through elite inclusion, without any reckoning with empire, exploitation, or power. Such representation ultimately reinforces coloniality rather than challenging it.

Mis-en-scène and the Appropriation of People of Colour

One way to understand this critique is through the lens of mis-en-scène: colours, symbols, costumes, props, and other visual elements that convey ideas and character traits through multiple modes. In Bridgerton, racial inclusion is largely visual: people of colour are present, in contrast to traditional “colour-blind” Regency-era dramas.

This inclusion, however, is superficial. The characters of colour are assimilated into a predominantly white setting, which trivialises what it means to be a person of colour.

To illustrate, consider this from a personal perspective. If I were a character in Bridgerton as a Sri Lankan Sinhalese woman, my identity would not be defined solely by the colour of my skin or a few selected cultural rituals. Being Sinhalese encompasses aesthetics of cultural artefacts, colours I resonate with, philosophy, worldview, and concepts of family, time, efficacy, romance, and aspiration. Yet in Bridgerton, I would have to wear a Victorian-era outfit and conform to European social norms to be accepted—effectively performing a coloniser’s identity even in a fictional world.

Bridgerton‘s Flattening of Characters and Culture

Over the first three seasons, characters of colour include Queen Charlotte (Golda Rosheuve), Lady Danbury (Adjoa Andoh), Kate Sharma (Simone Ashley), Edwina Sharma (Charithra Chandran), Simon Basset (Regé-Jean Page), and, in the upcoming season, Sophie Baek (Yerin Ha). Queen Charlotte and Lady Danbury represent Black heritage (without nuance regarding African diversity), while the Sharmas represent the Indian subcontinent, and Sophie Baek appears to represent East Asian heritage.

Though their skin tones vary, these characters share uniform behaviour, dress, and mannerisms that conform to a European, Victorian aesthetic. Cultural signifiers—like Indian jewellery or Queen Charlotte’s hair—are toned down to fit white conventions. Even rituals, such as the turmeric ceremony in Kate Sharma’s wedding, are cherry-picked and simplified to blend into a largely white cultural setting. This flattening of identity reduces rich, diverse heritages to decorative aesthetics, rather than authentic experiences.

Even actions and beliefs are coded in ways that align with white European norms. For example, Queen Charlotte’s depiction as a lapdog-owning aristocrat is more than a costume choice; it signals assimilation into a colonial, European way of being.

Coloniality and the Erasure of Other Ways of Being

Coloniality is a concept first coined by Peruvian sociologist Aníbal Quijano to describe the ongoing epistemic and ontological effects of colonialism. Colonialism did not merely seize land; it transformed the very subjectivity of colonised peoples, dictating what was considered beautiful, wise, elegant, or valuable. Colonial interventions reshaped knowledge, culture, and social norms—what some scholars describe as a form of cultural genocide embedded in social engineering.

Decolonial frameworks have continued to develop, unpacking the deeper and often visceral effects of colonialism and coloniality. Scholars such as Walter Mignolo argue that modernity, globalisation, and neoliberalism represent contemporary ways in which colonial logic continues to operate. Similarly, Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang demonstrate that liberation does not always equate to cultural freedom.

In their influential 2012 paper, “Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor”, they examine the emancipation of African Americans in the United States, showing that while legal and political liberation occurred, it was often limited to assimilation into a white-dominated social order. This raises a critical question: can assimilation to the coloniser’s society truly be considered liberation?

In contemporary society, awareness of cultural appropriation and political correctness reflects a growing recognition of these realities. Yet people of colour are still frequently expected, implicitly or explicitly, to modify their names, hairstyles, mannerisms, accents, behaviour, socio-cultural norms, and ways of thinking to align with Eurocentric cultural expectations. These changes are often necessary to succeed in environments shaped by coloniality.

Bridgerton conveys this message through its shallow approach to diversity. The show implies: you are welcome into the nobility and higher social class of Regency London, only if you assimilate to European norms. Even in a fictional world, this raises serious questions about whether the series offers genuine representation. The result is a sanitized, post-racial fantasy that is visually diverse in terms of skin tones but ideologically aligned with whiteness and empire.