The name Oriana Fallaci may not be familiar to younger readers. But for decades it was a household word around the globe; a name that evoked fear and respect among the world’s most powerful leaders, and frequent controversy in her home country.

The first official biography of this pioneering Italian woman journalist (who was also a successful novelist) is about to emerge in English translation. Its author, Cristina de Stefano, says Fallaci still has a lot to teach us about journalism today.

“I became a journalist because of Oriana,” recalls de Stefano. She read Fallaci’s collection of political interviews —

Interview With History as a teenager, and it inspired her to pursue journalism.

When she died in 2007, de Stefano recalls wondering who would write the journalist’s biography.

“I said to myself, Not you! It’s impossible because you are not in touch with the family and the friends so forget it, there will be another person already working on it.”

Light bulb by ColiNOOB (Pixabay License / Pixabay)

But it wasn’t impossible. Two years after her death, de Stefano was contacted by Fallaci’s nephew Eduardo, her designated heir. Eduardo had read de Stefano’s work and been impressed by her style. She was the journalist he felt most capable of giving Fallaci’s biography the effort it deserved.

All in all, the project took about four years. De Stefano’s first task was to review and catalogue all of Fallaci’s papers, to which she had full access — notes, manuscripts, even love letters. She hired research assistants, and collectively they contacted Fallaci’s many friends and colleagues, traveling throughout Europe and the US to interview them, racing to find them before they too died. Fact-checking all the information they compiled also took time.

“To be honest, I was worried because Oriana was very open to exaggerating things,” recalls de Stefano, laughing. “So I was expecting to find some untrue facts in her life, but in fact, it was not the case. Sometimes she exaggerated a little bit — she tended to be very epic in her personal narration — but in the end, I was surprised to find that everything she had told was true to real life. It was just put in an epic way.”

Fallaci’s career was as diverse as it was precipitous. Best known for her reportage and complex, in-depth interviews with public figures, her early reporting days saw her covering arts, culture and entertainment beats, first in Italy and then Hollywood. Tiring of this, she set her sights on the space program, becoming a fixture at NASA and close friends with many of the American astronauts (one of whom even smuggled a photo of her to the moon, at her behest).

Then her career took an unexpected turn — she leveraged her fame as an arts and entertainment reporter to demand to be sent abroad to cover the Vietnam War, and thus began a career as one of the world’s preeminent war correspondents. Whether hitching a ride on a US fighter jet in Vietnam or traveling with Palestinian guerrillas in the Middle East, her war reporting provided a conduit for her to enact the personal courage and bravery which she considered to be the most important quality in a person.

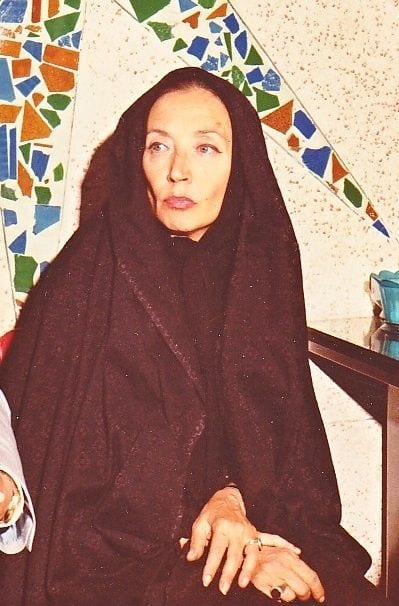

Oriana Fallaci in 1987 /GianAngelo Pistoia – Own work (CC BY 3.0 / Wikipedia)

The Art of the Political Interview

She was perhaps most well known for her political interviews. She pursued interviews with key public figures from around the world and across the political spectrum: from Princess Soraya of Iran (wife of the Shah), to Chinese communist leader Deng Xiaoping, to Polish rebel and trade union activist Lech Walesa. Her interview with Henry Kissinger is widely considered to have been a key factor in his political demise; she succeeded in drawing out his conceited arrogance in a manner no American journalist had managed.

A key component of her interviews, says de Stefano, was her tendency to treat them as theatre, with herself playing a leading role.

“She did an interview as a writer. She saw an interview like a piece of theatre… she was part of the interview. She was not just asking questions to a person, but this person was interacting with Oriana Fallaci as a character. And she had a good sense of timing.”

When she interviewed Iranian Islamic leader (and future dictator) Ayatollah Khomeini, she had been told to wear a chador (headscarf), which she did. During the interview, however, she confronted Khomeini on the matter of women’s rights and tore off the chador to make a point. Khomeini, incensed, stormed out of the interview. Fallaci refused to leave, insisting she’d been promised an interview and that she would stay until he returned. After a standoff of several hours, Khomeini’s son conceded her point, and the next day the future Iranian Supreme Leader obediently returned to complete the interview. Rather than be diplomatic, Fallaci continued the interview on the very same contentious point they had left it at the previous day (forcing the notoriously stern-faced imam to crack a rare grin).

In preparing for an interview, Fallaci did a tremendous amount of background research. She developed extensive files on all of her subjects, with elaborate lists of questions. The interviews themselves were sometimes full-day affairs, lasting at least several hours. Her goal was not just to ask a few questions, but to develop a more personal understanding of her subject. After hours of interviewing a subject, she would often request a follow-up interview, sometimes the next day. The follow-ups allowed her to test or confirm hypotheses she developed about the interview subject and their behaviour.

Fallaci in Tehran (1979). (Public Domain / Wikipedia)

“Then she sat in front of all this big material from the interview, and that’s the moment when she was [like] a novelist,” explained de Stefano. “Or a theatre writer. She created a piece of theatre. Sometimes she was extreme. I don’t deny it. For example, sometimes she went to an interview and she wanted the person to say something. And the person didn’t say it. So she suggested it, with the body language, with the observations. She had a kind of idea in her mind when she was creating an interview.”

“She’s a writer. She’s not just a journalist. She put a certain degree of creativity in. She doesn’t invent, but she’s very creative in the way she put all the pieces together. We [fact-]checked a lot of the interviews and she never invented a word or statement. But the way that you put the words of a person together, and the way you put the description of the person, [lets] you change the reality, in effect.”

“There are people who like her as an interviewer and people who don’t like her at all. You like it or you don’t like it… she liked to knead the person, to try to find the weak point. It was a real confrontation between her and the person… She always felt in the position to ask the questions, because she said ‘I am a journalist, I am here representing the reader, so I can ask you this question. It’s your problem, if you don’t want to answer.'”

The interviews she didn’t manage to do were almost as interesting as the ones she did. De Stefano’s work enabled her to gain access to Fallaci’s extensive preparatory interview notes, including files on people she never succeeded in interviewing. The vast majority of subjects she approached succumbed to the lure of being featured in a Fallaci interview; among those with the strength of will to resist the temptation were Cuban leader Fidel Castro and Pope John Paul II. It’s a pity Fallaci never managed to interview the Pope; her questions would have been revealing, de Stefano says.

“She was going to ask him questions about his sexual life, about the fact that he was a very handsome man, and big, you know — she was asking questions that you would never think of asking a Pope! She was also preparing to ask the Pope very hard political questions; Why are you fighting against South American priests who do politics, while you are helping the Polish priests who do politics against the Russians? Which was a good political question to ask the Pope. He was a very political Pope, but he had his own agenda, which was to fight the USSR, and not to fight in South America.”

Toward a More Creative Journalism

Journalism has changed considerably since Fallaci’s heyday, but de Stefano says the Italian journalist’s work offers important lessons for journalists today.

“I think that the most interesting thing in Oriana as a journalist was her way of dealing with power. Political power. I think that this is still very important. She was against power. She was a kind of anarchist, she couldn’t stand power — the power of politicians but also the power of the stage, the actors.”

“When you go to interview a politician, you have to be careful. Because today we live in a society that is based on image and politicians are showmen. Because of their image, because of their speech, they tend to charm people in a sense, to draw people to them.

“Oriana was always repeating that you have to try to see behind all this screen of fame. That’s something that I think is still important today, when you are informed of a person who has power — not to forget this is just a person. The way she wrote about big names, she was always trying to show the reader that they were a normal person, [who happened to be] just at the right place at the right moment. So I think this is good [advice] still now, and maybe more even now than before.”

A Political Cookbook

“She wasn’t impressed by power. She distrusted politicians. And so she can teach you to be wary, to listen to every word, for a journalist not just to listen to what they are telling you and record it, but to try to interact with the person… In the political interviews, I think she was very real, because she put herself at the same level as the person she was interviewing, and that was very new at that time. She was very brave, very personal in her way of dealing with them. She was not at all impressed by them.”Indeed, Fallaci’s journalism was very impressionistic and highly stylized. She didn’t hesitate to insert her own impressions and feelings into her journalism. In many ways, she challenged the notion that journalism should be purely objective and suggested perhaps that journalism’s other qualities were what really mattered.

“This is an old discussion, about objectivity and your own experience. Oriana was very sincere,” says de Stefano. “She was never pretending to tell you the truth. She was always telling you her own truth. I’m always worried when a journalist says to me ‘Okay, I went to Syria and now I will tell you what’s going on in Syria,’ for instance. Are you sure you saw the truth? So first of all, I think it’s very sincere to say to her readers: ‘This is what I saw, this is how I felt, this is the product of my interaction with my work in the field.'”

“Second, I think that especially today we live in a kind of globalized media situation. Everything happens everywhere and at the same time, everything reaches us. The problem is we have too much information, and we have to sort them out — fake news and all that… we have all the information about what’s going on in a country or what’s going on in a region, so a very personal look at a situation could add something.”

“In our times, when the media is everywhere and everyone can be a reporter — people with mobile phones can take images of everything around the world — we have a lot of information. So we need two kinds of journalists. One is the old-style journalist which checks this stuff, to be sure that it’s true. And for me, that means going to a big newspaper. When I see something on the Internet I go to The Guardian, or I go to Le Monde, I go to the two or three main journals that I trust to see if it’s true. That’s the first point.

“Now the second point — and this is where Oriana can still be useful — is that in all this… big mass of information, to have someone who is going there and is just telling me her own story, her own experience. It’s a kind of impressionistic journalism. You are going there as a writer and telling a story. I think that you still need this.”

“Oriana, of course, didn’t believe in objectivity, but she believed in writing, in the art of writing. When I read something written in the Oriana style, I enjoy the literary experience. If I need the factual journalism I go to Le Monde and just check the facts.”

“I think there is still a place to be very personal and literary in journalism,” says de Stefano, adding that the important thing is to make clear to the reader that that’s what you’re doing.

“And Oriana always did. She never said ‘This is the truth.’ [She said] ‘This is my truth! This is what I saw. This is the result of my experience, and as a painter, I give you my painting.'”

That type of journalism is perhaps more important now than ever, says de Stefano. “If we’re looking for simple facts, we have facts everywhere. On our mobile phone, or our Twitter. So if you are able, like Oriana, to be a real writer in the field, you can add something very personal. You can be different from the people with the mobile phone just watching and witnessing the Charlottesville riots. That [the riots are happening] is a fact. But if you have someone there who can really write and can tell the story on this, you have something new.”

A Feminist Fighter

To many, Fallaci seemed a woman of contradictions, and this was perhaps nowhere more evident than in her contentious relationship with feminism. She was a feminist before the word was in vogue. Yet she also did not hesitate to call out or challenge feminists — long before that, too, became vogue.

“Oriana was very good at infuriating people. I would say she was a specialist in this. She managed to fight every kind of movement and political party. This was her own speciality,” de Stefano explains, laughing. “In fact, she was a real feminist in her life. She never married. In her personal life, she was very feminist, in that she considered having a child without being married which was a big scandal in Italy at the time. She was a feminist in her professional life because she wanted to be a journalist in a period when women did not do journalism — and she wanted to be a political journalist! So she was absolutely a feminist.”

“But at the same time, I think she did not like the movement. You know, feminism — everything that is an ‘ism’ — she had a kind of problem with every political movement. Because she was a kind of anarchist. She had a problem with power. So when she was in America, she got involved with the American feminists, but she didn’t like the way it was going to be a real political movement. She always said that she didn’t like the way that American feminism was against men, and that she thought that you had to be able to be yourself as a woman without being in conflict with men.

“But I think that in reality, it was just that Oriana didn’t like political movements, didn’t like the gathering of people. She was a very individualistic person. And she was convinced that she could do her own feminism by herself without being part of a movement.”

To further complicate her perception among feminists, in 1975 she published Letter to a Child Never Born (1977), in which she spoke to her unborn child. Fallaci never had a child, although she wanted to be a mother and did become pregnant and miscarry on multiple occasions. In the book, she shares her conflicts, dilemmas, and doubts with her unborn child — her desire to pursue her career without being burdened by obligations, versus her joy at the thought of having a child. In the end, she miscarries. Published at a time when abortion was under intense public debate in Europe, the book generated a firestorm of controversy, infuriating both sides of the abortion debate.

“[She was] very strongly in support of abortion,” emphasized de Stefano. “And that’s the amazing thing, that in this book she managed to infuriate the pro-abortion camp and the anti-abortion camp with just one book, the same book. Because that’s the way she was… I think that she was able to describe the complexity of the position of a woman on this subject and she was very very fierce, very clear in her position. She published the book in Italy when the Italian people were discussing a law on abortion and there was a big fight in Italy over this, and she went on the TV and she said ‘Without any doubt, I will never abort my own baby. But I will fight for the right of other women to abort their baby if they want, because this is only a woman’s choice.’

“On this she was completely clear. She said that personally, she would never do it, but she was absolutely in favour of the right to abort for a woman. And she was very, very strong in her support. She was on the TV stage with some politicians from Italy, and she said ‘This is the problem of a woman. You men can’t talk about it. You let the woman decide because it is just the woman who has to have the burden of having the baby or not having the baby, because it can be a burden and you can’t judge a woman for this.’ She said in an interview, this was a book on doubt. Not a book on being sure of something.”

Fallaci’s apparent contradictions, however, and her ‘anarchist’ side, make more coherent sense when one considers the impact her childhood growing up during the Second World War must have had on her. Her family were staunch socialists and anti-fascists, and as a girl, she fought with the Italian resistance. As a 14-year- old, she smuggled hand grenades (hidden in heads of lettuce in the basket of her bicycle) to anti-fascist resistance fighters. Her family hid escaped Allied POWs in her bedroom. She transported secret messages hidden in her braids. When Nazis captured Allied soldiers, whom she was trying to help rescue, she witnessed first-hand their brutal treatment. The imperative to fight fascism, and the domineering and oppressive principle it represents, had an indelible impact on the worldview she was to develop.

“I think that her childhood during the war and in particular the year she spent fighting in the Resistance from ’43 to ’44 was really the beginning of everything,” says de Stefano. “It shaped her idea of life.”

De Stefano says the war crystallized three key ideas for Oriana, to which she clung throughout the rest of her life. First was her epic view of the world, and the way she saw events around her and her own role in them in an epic and dramatic fashion. Second, it shaped her passion for bravery; the idea that being brave was the single most important quality in a person. Third, says de Stefano, it shaped her notion of “life as fighting”.

“Oriana was a person who was always fighting — in her personal life, in her professional life. For her, the world is made of war — political war, personal war… She used to say ‘If I write a cooking book, it will be a very political book.’ Because for her everything was political.”

The war may have given her a view of life as a battle, but it also shaped her views on love, says de Stefano.

Typical Fallaci Ferocity

“Her ideas on love, on men, were made at that time. She had to always be in love with a hero. She couldn’t imagine how not to be in love with a man who was very brave and courageous and a heroic man, and that also came from war.”

For someone who had a reputation as a fearless war correspondent with a penchant for confronting the most powerful people in society, Oriana’s romantic side came as a surprise to her biographer.

“She was hyper-romantic! I was really surprised when I was reading her love letters — I couldn’t believe my eyes. You know every person is a contradiction. She was very, very jealous of her own independence. And at the same time, she was very passionate, very romantic. I think she, at some points of her life, was ready to give up everything for a man, which is quite strange in a woman like this.”

Some of her romances sound like the stuff of fiction. In 1973, she interviewed Alexandros Panagoulis, a Greek resistance fighter against the ongoing military dictatorship in his country at that time. He attempted to assassinate the head of the military junta with a bomb, but it failed to go off and he was captured and imprisoned for several years before being released in an amnesty. Following their interview, Panagoulis and Fallaci fell in love and began a relationship which lasted until Panagoulis’ tragic and suspicious death in 1976 (in a car accident that some believed to have been an assassination). In 1979 Fallaci — who was a successful novelist as well — published a novelistic biography of Panagoulis chronicling their relationship, which she bluntly titled A Man.

The Rage and the Pride

On 11 September 2001, Fallaci was living in New York. She was old, retired, and dying of cancer. Not that that slowed her down — she was writing what she intended to be her opus, a sweeping multi-generational novel based on her own family history. The terrorist attacks shocked and horrified her. They also propelled her to turn her pen away from her novel and back to politics. What ensued were two books — The Rage and the Pride in 2001 and a follow-up titled The Force of Reason in 2004 — which tackled the issue of political Islam, with typical Fallaci ferocity.

The books, de Stefano says, “destroyed her reputation as a journalist.”

Which is not to say they weren’t popular — they were both bestsellers, selling millions of copies. But Fallaci’s violent language sparked widespread outrage and accusations of Islamophobia, as well as lawsuits.

“Like a lot of readers I was disappointed by Oriana after the Twin Towers attack,” de Stefano recalled. “She lost almost all her readers, and she became kind of an icon of the right-wing press in Italy.”

De Stefano was also disappointed in her hero and felt she’d finally gone too far. When she approached the topic in her biography, she struggled with how to present it.

“I put this in the context of her life,” she explained. “I understood that’s the way she was. She was not diplomatic, she was not very optimistic in general. She had a very pessimistic vision of the world. She was convinced that war was everywhere. So for her, the Twin Towers attack was just the confirmation of her pessimistic view on the world.”

The most difficult part of writing Fallaci’s biography, says de Stefano, was the chapter on Fallaci’s post-9/11 work.

“I was really worried by this chapter. It haunted me because I knew that it was an important part of her life but I didn’t want it to overshadow the rest of the story. Someone criticized me in Italy recently saying that I was too nice on her in this chapter, but I think that I wanted to balance the information. I wanted the 9/11 story to be one of the stories of her life, without overshadowing the rest.”

“Maybe I was too nice but this was my choice, I wanted to put all this in perspective. Because if you google Oriana [all] you get is Islamophobia and Islamic issues. That’s her image today, and I wanted it the other way around.”

“I can’t say if she was Islamophobic because I don’t like the word. Islamophobic means that you are afraid of Islam, and she wasn’t afraid of Islam. She was worried, she was critical, she was convinced that Europe was too weak and was not ready to stand up for its own values.”

“Myself too, as a reader, I was disturbed by the book, I remember very well. But when I thought over and over about this book I realized that I was disturbed by the book because the book was pointing at me, at my culture. It was more than what she was saying about Islam. In the end, she is saying in the book that Islam is very young and very aggressive and full of energy. If you see the world as a war, she is suggesting that Islam will win. So she is not criticizing Islam, she is criticizing Europe — saying that Europe is old and tired and not ready to fight for what she believes in. So I think that that’s the main point that disturbs a European reader.”

Researching her biography, de Stefano says it didn’t change her disagreement with Fallaci’s political positions or the violent language that she used. But it did help her to understand the context in which she wrote it.

“I think she was wrong on supporting the invasion of Iraq. But she was very isolated, she was very old and sick, she was not in the middle of the action. She was retired… she was not aware of the way she was used by the newspapers in Italy.”

Fallaci firmly resisted new technology in her old age. She continued writing on a typewriter and refused to use the Internet. De Stefano wonders whether she might have acted differently had she known how her work was being appropriated by right-wing conservatives.

“I found some letters of her sister writing to her saying ‘Our father would be outraged because… you are now the icon of the fascists and the conservative press.’ So I am not sure she was aware of how she was viewed by the conservative press because she was out of the scene. She was an old lady… When you get old the world seems a very difficult place for an old woman, and she really believed 9/11 was like the end of the world. It was the kind of an end of the world, and the beginning of a new world and she couldn’t find a place in this new world. So her last work was very negative, very pessimistic, very dark.”

“My book asks the reader to put all this in perspective. Because we shouldn’t remember just the last words of a person and forget their long and full life. Let’s try to remember that she was very old, she was very alone, she was very sick, she was dying, and she saw something that was new — a new kind of war, a new kind of terrorism, and the beginning of something big, huge — so for her it was a kind of big shock. And the book was the result of this huge shock.

Fallaci’s Legacy

Fallaci’s tumultuous life is difficult to sum up in a single book, but de Stefano’s work offers a deeply perceptive insight into the fascinating Italian journalist, delivered in a riveting and engaging narrative style that’s evocative of Fallaci herself. De Stefano never had the chance to meet Fallaci while she was alive, which she feels allowed her to approach her work with greater neutrality. But in the end, she says she came away from the project with a greater appreciation for the journalist.

“When I started to work on Oriana I was not very empathetic to her at all,” muses de Stefano, her voice ringing with laughter. “She was not a very nice person. She was a difficult person, she was very dramatic, so I was not so keen on her… I think that working on her I ended up actually appreciating her more than when I started because I was impressed by how hard she fought to go where she went. How difficult her life was because she was a pioneer. She was a woman doing a job, journalism, when nobody did this kind of job as a woman in Italy. She really had to fight to show that she was good, even better than her colleagues, and I think that at the end of my work on her I was more impressed by Oriana than when I started working on her.”

“I think that we need great people,” says de Stefano. “She was a diva, you know. She was one of the last divas of the last century. She was so elegant, so feminine, so expressive… And at the same time, I think she can still be a source of inspiration for journalists.”

“I think we should remember Oriana as a ground-breaking woman who realized something big for a woman of her time… And I think she can still be an inspiration for readers. Because she teaches you to fight for what you believe in, to always pursue your dreams.”