When Dead Can Dance announced they were disbanding in 1998, their fan base around the world mourned the news. For nearly two decades since their founding in Melbourne in 1981, the duo of Australian-born Lisa Gerrard and Irish-born, London-raised Brendan Perry had regaled audiences and listeners around the globe with their unique style of gothic, experimental world music.

Yet as it turned out, Dead Can Dance found it difficult to stay dead. While both artists pursued personal careers through a range of solo and collaborative projects, the duo reunited for a brief tour in 2005, and in 2011 released a full new album, Anastasis, which they toured and performed as well.

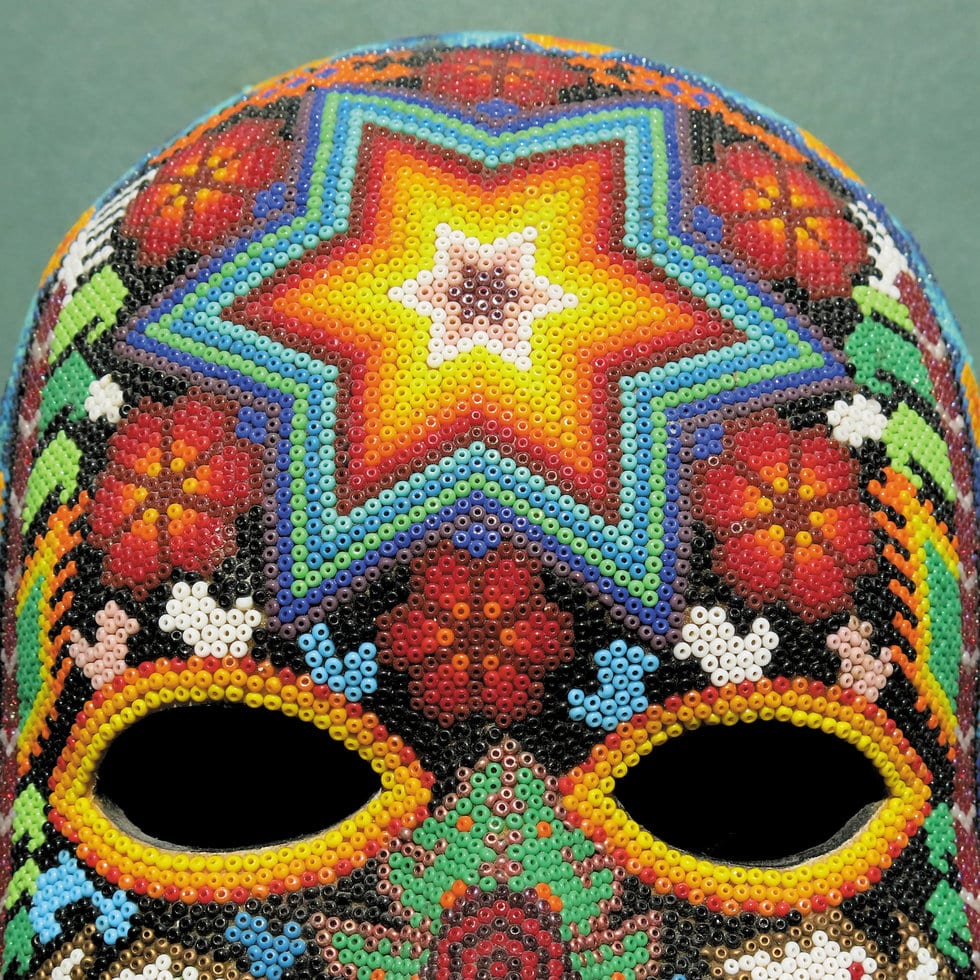

Now they’ve released another brand new album: a short, beautifully constructed ‘oratorio in seven movements’ titled Dionysus. In all their nearly 40-year career, it’s the group’s first concept album and shows the two artists’ remarkable capacity to continue innovating and inspiring under the moniker of Dead Can Dance. What is it, precisely, that drives the group’s remarkable staying power?

“Just passion, really,” reflects Brendan Perry. “Just a belief in, and love for music as a medium for communication. Not only that, but for me it works on many levels: for healing, meditation, as a vehicle for research in various fields of culture and traditions. At the heart of it really is having a curious nature, and a perpetually curious nature that is insatiable, to want to learn and know more about the world.”

It was only a matter of time until Dead Can Dance produced a new album, he says. Life changes stretched out the gap: while Gerrard pursued a prolific career of her own, over the past few years Perry and his family relocated from Ireland to France. He also had to build a brand new studio for his work. It’s important, Perry notes, for the two not to feel pressured in their musical work.

“We make albums when we’re ready to do them, and we’re in no rush to meet anybody else’s criteria,” he says. “We don’t have contractual obligations to anyone at all, so we’re kind of free-spirited in that sense.”

The idea for the latest album was sparked two years ago when Perry read Friedrich Nietzsche‘s The Birth of Tragedy Out of the Spirit of Music (1872). The book explores Nietzsche’s idea that there are two main strands running through Greek cultural creative thinking: the Apollonian — organized, analytical thinking, grounded in reason and the intellect — and the Dionysian — “which is much more sublimated, much more profound, stemming from dreams and nature and energy and much more chaotic and less predictable. A kind of unpredictability,” Perry explains.

“It was kind of a revelation, that book, to me,” he says. “These two strands, when they come together and they merge into one creative art form — essentially musical theatre — they create the most sublime art. And that was a real revelation for me because we kind of do that, myself and Lisa. That’s very similar to our dynamic, the way we work, and what we’ve written in the past comes from this organized strictness, but with a very improvised, kind of fluxus, wild aspect to it as well.”

This sparked what became a passionate interest in Dionysus on Perry’s part: he consumed books, documentaries, and all the material he could get his hands on. As he studied and learned, he decided Dionysus would make a great subject for a piece of music. But before he began working on the musical arrangements, he immersed himself in further reading and research around Dionysus and the god’s various iterations, festivals, and customs. There’s much in the myth, he says, that ought to resonate deeply with people today.

“Dionysus is very much connected with nature and those forces within nature, within the cosmos, that are still mysterious to us,” he explains. “But they’re also deeply rooted in the agrarian and rural traditions of country people. Increasingly the world’s population is becoming more and more urbanized, and we’re losing our connection with nature because of these urbanized environments that we’re living in, and so this disconnect is really kind of worrying for the future. If this continues, we won’t have much of a planet.”

“I think there is a lot to be learned from having a connection, a more Dionysian kind of connection,” he says. He shares his knowledge enthusiastically, explaining the shift over centuries from Dionysus’ origins as an agrarian deity worshipped through the cycles of planting and harvesting, to his more decadent iteration as Bacchus in ancient Rome. He explains how Christian spin and propaganda associated Bacchus with hedonism, in an effort to suppress that and other cults which served as rivals to early Christianity. The remarkable thing, he says, is despite nearly two millennia of Christianity’s efforts to eradicate Dionysian customs and beliefs, they still survive in many parts of the world.

“I’m just really constantly surprised when I see people still celebrating these very old pagan customs in these remote locations around the world, celebrating nature and the planting, spring, and harvest. They’ve been doing that since the dawn of time, basically.”

Perry reflects on some of these customs he’s witnessed over the years, in Spain and elsewhere in Europe. Even his own upbringing, he realizes, was interlaced with that tension between urban and rural; between modern, consumeristic city life and ancient, pagan village traditions.

“I was brought up in London, but my Irish family were farmers, so every summer holiday and Christmas I would leave the big smoky city of London and then we’d go on a ferry across the Irish Sea to Ireland,” he recalls. “I’d spend six weeks in the summer, harvesting with the local kids on the farms, and it was really very beautiful. My memories of it are very strong. And it’s that dynamic, that contrast, that you see. I mean we had pagan festivals too, there’s a lot of old pagan stuff going on in Ireland that predates Christianity which I was aware of at an early age. But I do see it as very much of a universal thing, and it’s very much connected with rural people in the countryside who have first-hand experience of working within nature, realizing it’s what sustains their lives and gives reason for their existence.”

As we lose contact with nature and the natural cycles, we lose a part of ourselves, he says.

“And we are losing it. It’s sad. As the population becomes more centralized we don’t have firsthand knowledge through people that we know, through family, of what it is that we’re actually losing. We’re talking about serious depopulation of rural areas that’s being replaced by this new agrarian revolution of machines. We’re using more pesticides to produce more and more food for an overpopulated planet. No one seems to be talking about our population problem but we have a huge problem that no one seems to be addressing … it’s just going crazy, and the world can’t sustain the amount of resources required for this. And also health-wise people who live amongst nature are far healthier. They look healthier, they’re breathing better air.

“It’s just mindboggling that people would gravitate toward cities, especially in this day and age … for the health of the world and the health of humanity we need to reconnect. Get back to the garden, as Joni Mitchell would say.”

A Musical Oratorio

Perry and Gerrard have been working on Dionysus for the past two years. Like most Dead Can Dance albums in recent years, the routine has been for Perry to develop the initial themes and ideas, and do the foundational work on the album before Gerrard comes in to record. With Dionysus, Perry spent about six months working on the initial arrangements and compositions, and Gerrard came to stay with Perry for a month last November to record vocals. The two also collaborated on the album by distance.

But this album marks a departure in many respects from their previous work, Perry observes. It’s their first concept album; the first time they’ve themed an entire work around a single idea.

The album differs in its musical structure from previous Dead Can Dance albums as well.

“We made the decision that we were not going to do songs for this,” explains Perry. “And that all the voices would be sublimated into essentially a kind of Greek chorus, a collective choral group … this is a different beast, this is a departure, we wanted to do something new. We didn’t want to go over old ground. This was something that would challenge us to do something different.”

Translating the complex themes which surround Dionysus into a cohesive musical piece produced conceptual challenges as well.

“I decided I needed to approach it from an impressionistic point of view because I realized this was an incredibly complicated subject,” Perry explains. “So I decided I would just look at different facets. I took what I considered to be the most important aspects of the Dionysus mythic tales and they became the movements, the seven movements. And they kind of metamorphose into each other.”

The result is remarkable: one of the most stunning Dead Can Dance releases yet. The majestic album retains all the mysterious, ethereal elements of the band’s trademark ritual Gothic style, yet combines this with a majestic neo-classical aspect; irrepressible drumming and rhythms which convey a movement simultaneously wild and impeccably controlled; soul-stirring vocals; all contained with a sense of unity and flow that perfectly summons a vision of the natural world, replete with sampled winds and waves and animal cries.

The seven movements are each grounded in different elements of Dionysian myth: the god’s arrival from the east by sea; the bacchanalian dance and mind-expanding rituals; harvest ceremonies; the journey to the Underworld, and more.

Perry originally wanted it to be a single continuous, unbroken piece, but eventually gave in to splitting it into two acts in order to accommodate the vinyl release, which provides one act on each side. They deliberately decided to keep it short in order to ensure higher audio quality.

“The foundational work, as with most Dead Can Dance albums, was to choose which kind of instrumentation we were going to use. I opted for the initial bedrock foundation of instruments that were from traditional folk cultures from around the Mediterranean. So I used lots of shepherds’ flutes, different types, with lap-held violins such as the gadulka, and some stringed instruments like various dulcimers and percussion basically from North Africa and Anatolia. That was the bedrock.

“Then the second stage was finding instruments that could mimic animals or nature, elemental forces like wind and rain or moving water, and whistles that could mimic birds,” he continued. “I felt that because it was about the natural Dionysus we had to have musical bridges that would connect nature and a celebration of nature — so what better way to celebrate the animals than to actually mimic them and try to communicate with them in that sense? And that’s interlaced with field recordings of the sea, and goats with bells in mountain passes and insects and various other creatures, to give it a dramatic outdoor kind of ambient feeling. So you feel more as if you’re kind of immersed in nature.

“The last part really was the chorus, which I opted for because Dionysus is very much associated with the birth of Greek theatre. The Greek festivals were dedicated to Dionysus, [so] I felt that it was really important to include a choral group that represented a collective like the Greek chorus was. Before actors, there was chorus — the body of singers and storytellers. And that’s essentially how it was all built, from beginning to top.”

What Perry found particularly exciting and innovative was the construction of the chorus. Drawing on new technology, he was able to work in a chorus that sings in an entirely invented language.

“The thing that was a real revelation for me was [the chorus]. It would have sounded really strange if myself and Lisa had tried to do all the voices and build this choral group — it would have sounded quite synthetic, and I really wanted it to sound like it was a real group from a village, some rural village, singing. So I came across these vocal libraries which have this special technology, they’re called Syllabuilders. And what that is, is basically they have directories of syllables, and you can actually write in your own phrases, and invent your own sentences and words. And then you can play them polyphonically, and they will sing your harmonies — those sentences and phrases that you’ve written into this engine. That was really amazing … it’s real voices, you know, but you’re actually telling them what to sing, which is quite phenomenal. With vocal libraries in the past you were kind of stuck with one phrase, and then you could harmonize a little to a degree, but this new technology is a giant leap forward. So what we did was then we superimposed our own voices with these voices to create a chorus.”

The entire process took them two years of work. The complex technologies and musical compositions wasn’t the hard part, he reflects. What he found most challenging, he says, was “keeping focused.”

“It’s difficult when you work alone because everything is a lot slower as opposed to working with a group of people. You just have to keep that idee fixe, fixed in your mind and work towards it. And it takes time, you know. It’s nice to slip off into various tangents here and there, but you can get lost up these rivers that have no ending, or they do end and there’s no outlet for them. Keeping focused is the hardest thing when you’re working by yourself.”

Fusing Cultures

In an age when sourcing, attribution, and rights over not just produced works but entire cultural traditions are hotly contested, creative works which draw on broad global traditions sometimes find themselves embroiled in controversies around cultural appropriation. It’s not a new phenomenon: from the earliest days of jazz to the punks who drew on African drum rhythms, musicians who hybridize musical traditions to both play traditional music as well as produce new forms find their work sometimes challenged. Perry reflected thoughtfully on challenges musicians can face in navigating these increasingly contested domains.

“It’s a difficult one,” he agrees. “Cultural appropriation is something that I think is important and relative to a culture which is still trying to be acknowledged, and still trying to carry on its own traditional ways. I think it’s really important to respect living cultures. Cultures which have moved on, and no longer exist, for instance — that’s fine, it’s fair game, it’s open to interpretation anyway.

“I have mixed feelings on it, in the sense that I think hybridization, or change, especially in music and also on [other] levels too, is a necessary prerequirement for moving on, for telling a new story. I’m a little bit anti traditions which are stuck, like at some point someone decided this is what traditional music is. I mean this happened to Irish traditional music for years, and it was disgraceful. They kept it in a bubble basically, and that was all part of Irish nationalism. Wherever you see nationalism connected with the arts, that’s what they tend to do, they tend to say ‘Right: all the development and evolution stops here, this is the top, this is the best it will ever be, this is the benchmark, everything has to conform to this.’ Or it will not be taken seriously.

“Folk music in Ireland really suffered from that for years, until groups like Planxty came back from the Mediterranean with bazoukis and weird time signatures and stuff like that, and introduced it in the seventies into Irish folk music, and then it changed. So I’m all for pollinization and change. But at the same time, respecting music’s culture, or at least giving reference to them in the music that you do. As long as you’re not stealing directly, without giving due credit, then I think it’s fine.”

From Studio to Stage

Fans will have to settle for listening to Dionysus recorded, as Perry and Gerrard do not plan to perform it live. Doing so with live performers would be complex, he says, and pose challenges of how to convey the broader concepts of the album on a stage. But at the same time, after two years in the studio Perry’s yearning to perform live.

So Dead Can Dance will be hitting the tour circuit this summer, with what he describes as “a celebration of our musical legacy.” He said many of their younger fans have never had the chance to hear the band’s early material from the ’80s and ’90s performed live, so they’ll be performing much of that work during their tour. They intend to include a number of pieces that they never performed on stage even during those early decades, and also to re-work a lot of their older material into new forms. Perry sounds excited as he describes the plans. While they’ll only be touring in Europe this summer, they do hope to expand the performance into a world tour by 2020, spanning the entirety of the Americas as well.

2020 will mark the band’s 40th anniversary, and Perry laughs when I point it out. I ask him what he’s most proud of when it comes to the band’s musical legacy, and the gentle, soft-spoken musician takes a few moments to think, pausing in his characteristically thoughtful and deliberate manner.

“I think probably that we’ve turned on a lot of people who wouldn’t be aware of different musics from around the world. Hopefully, we’ve opened their minds a little, made them a little bit more worldly and appreciative of other musical genres and traditions. I think that’s probably what we’ve added to the mosaic of human culture and tradition in the musical sense. Pride isn’t a word I often use, so I wouldn’t use it. But I’m happy, there’s a sense of achievement on that level. I feel that we’ve contributed greatly in that department.”

In addition to the upcoming Dead Can Dance tours, Perry is finishing up a new solo album which he hopes to release next autumn. He’s also doing a European tour of his own — western Europe in the spring, eastern Europe in the fall. He’ll be performing his own work as a small trio, playing in intimate venues around Europe. He says that given the choice, he prefers live performance over studio work — the travel and the opportunity to meet new people is something he still finds most fulfilling, he says.

“After two years of working in the studio, I feel like it’s time to get out and dust off the cobwebs and start performing,” he laughs. “It’s what I love to do.”

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)