Android Face by bluebudgie (Pixabay License / Pixabay)

In early 2004, while filming Blade: Trinity (Goyer, 2004), director David S. Goyer introduced actor Ryan Reynolds to the Marvel Comics character Deadpool. Around the same time, in Cable & Deadpool #2 (June 2004), Deadpool refers to his heavily scarred face as looking like “Ryan Reynolds crossed with a shar-pei.” Reynolds and Deadpool were destined for each other.

Reynolds immediately expressed interest in starring as Deadpool in a big-screen adaptation. 20th Century Fox, which owned the film rights to the character through the X-Men, were interested as well. Fox executives insisted that Deadpool, played by Reynolds, debut in X-Men Origins: Wolverine (Hood, 2009) as a lead-in to a Deadpool film. Wolverine, however, was an absolute mess, mishandling every character and even basic storytelling. Arguably no character was handled worse than Deadpool. The character is given an altered, nonsensical origin, different powers than he has in the comics, and his mouth is sewn shut!

For context, Deadpool is a character best known for his constant wisecracking, earning him the nickname, the Merc with a Mouth. Sewing his mouth shut in his big screen debut is the clearest example of filmmakers misunderstanding a character that I have ever seen. X-Men Origins: Wolverine was a serious blow to Reynolds’ plan for a Deadpool film, and in most cases that would have been his first and last chance.

Luckily, X-Men Origins: Wolverine earned a decent opening weekend gross before viewers realized it was terrible, and Fox immediately began development on Reynolds’ Deadpool film. Just days after Wolverine‘s opening, Reynolds gave interviews promising that his solo film would be much more faithful to the character. He teamed with writers Rhett Reese and Paul Wernick, fresh off their success with Zombieland (Fleischer, 2009), to write the screenplay in early 2010, and hired Tim Miller to direct in early 2011.

Deadpool was on its way to production when it hit another major speed bump: Green Lantern (Campbell, 2011). The Warner Bros.-produced, DC Comics adaptation starring Reynolds was a major critical and commercial disappointment, and Fox soured on the idea of Reynolds headlining their next major superhero film. The studio suddenly pushed for a less risky PG-13 rating rather than the planned R. Fox gave Miller nearly $300k to create CGI test footage as proof of concept for the film, but remained unconvinced. After the success of The Avengers (Whedon, 2012), Fox insisted that Deadpool be rewritten as a team film rather than a solo film. And this is how the project languished for three years. No wonder Ryan Reynolds hates Green Lantern.

Leslie Uggams as Blind Al and Ryan Reynolds as Wade / Deadpool (IMDB)

Wade Wilson’s moral compass is whacked.

This is a unique, refreshing approach to a superhero,

the scarily hilarious or hilariously scary approach.

In July 2014, Miller’s test footage leaked online and became a sensation. Fans of Deadpool started a campaign in support of the film. In September, Fox finally greenlit the project, albeit with a budget much smaller than most superhero films. The leak worked miraculously well, and it’s a poorly kept secret that Reynolds was the leaker. Two days before filming, Fox cut the budget by $7-8 million (11-13%). The studio did something similar when it cut the budget of

Fantastic Four (Trank, 2015) by 25% right before filming, indicating a baffling, self-sabotaging pattern of behaviour. Reynolds and his collaborators scrambled to make the adjusted budget work, but they remained thrilled that their longtime vision for Deadpool was finally coming to fruition. Ryan Reynolds’ 11-year quest was reaching its end.

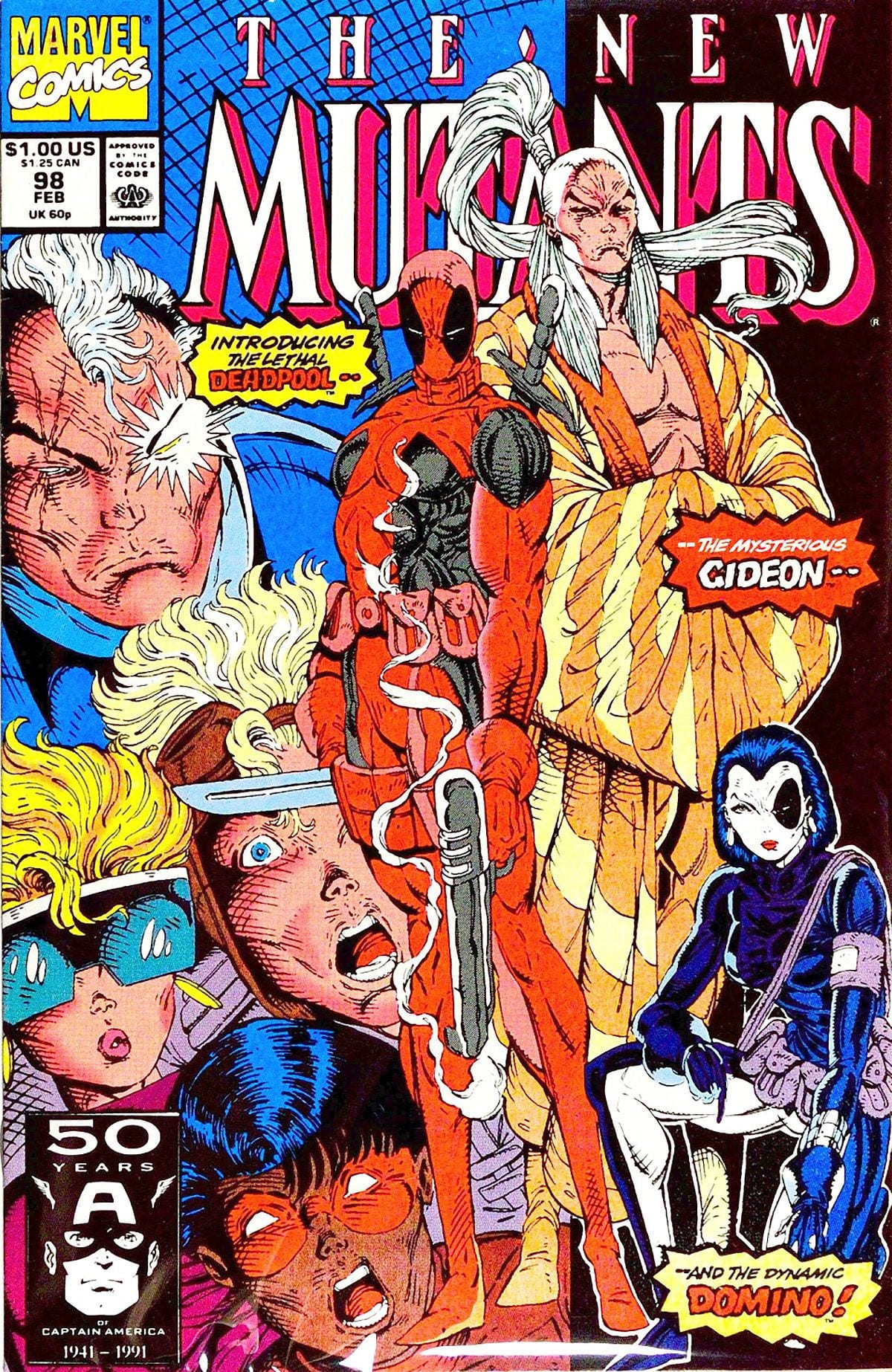

Deadpool first appeared in

New Mutants #98 (February 1991), written by Fabian Nicieza and drawn by Rob Liefeld, as a mercenary hired to kill Cable, the leader of the New Mutants. Incidentally, this makes Deadpool the most recently created Marvel Comics character to headline a film to date. The character, conceived by Liefeld, shares his appearance, weapons, profession and some abilities with the DC Comics character Slade Wilson/Deathstroke, who was introduced over a decade earlier. Liefeld “borrowed” these traits shamelessly, even giving Deadpool the civilian name Wade Wilson as a knowing wink. Liefeld and Nicieza also included traits inspired by popular Marvel characters, notably Wolverine (super-healing, violent streak, Canadian) and Spider-Man (constant wisecracking).

Despite all of these borrowed traits, Deadpool is mostly a product of his time: early-’90s superhero comics. In this era, new characters exactly like Deadpool were popping up all over. They all tended to be violent antiheroes with mysterious origins, big weapons, bad attitudes, and truly terrible dialogue. Comics publishers decided in the late-’80s that readers wanted “extreme” characters and the result is widely, and rightly, viewed with scorn in retrospect. Unlike most early-’90s “extreme” characters, however, Deadpool has endured and thrived in the decades since his debut.

The character made further guest appearances in Marvel Comics before starring in two miniseries in 1993 and 1994. The first Deadpool ongoing series debuted in 1997, written by Joe Kelly, and that is when Deadpool as most people know him truly emerged. Kelly dialled up the humour of the character, and used him to mock or satirize trends in comics. This element is the reason that Deadpool has stood the test of time. The comic book world can be a little over-serious. It needed a comedic foil, and found one in Deadpool.

Kelly also cranked-up the pathos of the character, precariously balancing his goofiness with his psychotically poor judgement. Wade Wilson attempts to be a hero, but his lack of a moral compass make these attempts twisted and misguided, to either humourous or horrific ends. This was a unique, refreshing approach to a superhero, the scarily hilarious or hilariously scary approach. Other aspects introduced by Kelly were Wade’s friend/prisoner/roommate Blind Al (Leslie Uggams), his sidekick Weasel (T.J. Miller) and, most important of all, the breaking of the fourth wall.

“Breaking the fourth wall” is a theatrical concept dating back to at least the 17th century. The idea is that there is an invisible wall at the front of a stage separating the actors from the audience, since characters in a play ignore the audience. For a dramatic character to acknowledge the audience “breaks” the fourth wall. Wade is aware that he is a comic book character, allowing him to call out tropes or address the reader. Other characters within the comic just assume this is psychosis. Future writers would build upon these elements introduced by Joe Kelly.

The first Deadpool series was cancelled in 2002, and the character was relaunched in Cable & Deadpool. This series sees two quintessentially early-’90s characters teaming up in a violent odd couple/buddy cop romp. Following that 50-issue series, Deadpool received a new solo series in 2008. In 2009, a second ongoing solo series began, then an ongoing Deadpool team-up book later that year and a multidimensional Deadpool Corps book in 2010. Additionally, Marvel published an endless string of Deadpool-centric miniseries satirizing various comic book trends, and Deadpool joined superhero teams such as Uncanny X-Force.

As the ’10s progressed, it was common for four Deadpool books to be published each month, not including appearances in team books. Hence, Deadpool emerged as one of Marvel’s most popular characters. Also, the blockbuster market had become so saturated with comic book films that Deadpool’s character could easily satirize films the way he satirizes the comics. For both of these reasons, 2016 was the perfect time to introduce Deadpool to the world outside of comics.

This introduction began with the film’s marketing. I don’t often discuss the marketing of films, but the campaign for Deadpool was some of the most unique, brilliant advertising I have seen for a film. It made liberal use of Reynolds in the Deadpool costume, and the character’s fourth-wall breaking, to ensure that the public was fully aware of the look and humour of the film before they saw it. There were videos of Deadpool trick-or-treating with kids and asking them inappropriate questions around Halloween. Multiple film news sites participated in the 12 Days of Deadpool, with different sites releasing new content about the film each day leading up to a trailer at Christmas.

Reynolds started a fake online feud with Hugh Jackman. Reynolds ran a taco truck and a pop-up bar near the stadium on the weekend of Super Bowl 50. Billboards and other advertisements promoted Deadpool as a romantic Valentine’s Day film, with the tagline “True Love Never Dies”, in the lead up to its 12 February release date. Reynolds, as Deadpool, filmed a public service announcement about the proper ways to screen for testicular cancer. He even appeared in character with Betty White in ads for the Manchester United Football Club. All of this was hilariously appropriate to the character and spread awareness of the film to unlikely places. It also exhibited the passion Ryan Reynolds had for the character. None of it felt cynical or rote, which was refreshing.

Stan Lee as the Strip Club DJ (IMDB)

This effort would have gone to waste if Deadpool was a poor film but, luckily, this is not the case. The best superhero films capture the proper tone for the central character. If that is the measure of success, then Deadpool is one of the greatest superhero films of all time. The film includes the visceral violence, cartoonish humour, and affecting drama that are essential to a faithful Deadpool adaptation, and keeps them in proper balance. Deadpool has a very conventional plot, but delivers it in exciting an unconventional way that works for the character. This is made possible by the R-rating which, though not appropriate for most superheroes, allows Deadpool full licence to include a level of violence and vulgarity that are arguably necessary for the character.

I don’t offer praise of this film lightly. Deadpool had to win me over. I don’t like early-’90s comics, and Deadpool always seemed like a holdover from that awful era. Indeed, as the character grew in popularity, his ubiquity became a turn-off for me. But what I later came to realize is that Deadpool outgrew his origins and vastly improved over time. Later writers leaned into the humour and pathos, and also used him to satirize other comics. This is why the film works, and this is what won me over.

The opening titles immediately set the tone and expectations. Deadpool begins with the unexpected musical choice of Juice Newton’s “Angel of the Morning” playing over the frozen image of a man with a burn on his forehead spitting out a car cigarette lighter. As the song plays, the camera moves through a frozen fight scene in a crashing car. As the shot moves around, we see injuries and various debris such as Ryan Reynolds’ 2010 People Magazine Sexiest Man Alive issue, Reynolds visage appearing on a Green Lantern trading card, and a Hello Kitty chapstick.

We are also gradually introduced to Wade Wilson/Deadpool (Ryan Reynolds) in the middle of the action. He’s sitting on one man’s face, poking another man in the eyes, and grabbing a third man, who is outside the crashing car, by his underwear. It’s all there from the beginning: the violence, the crudeness, the cartoonishness, the pop culture humour, all displayed by moving through a stunningly inventive frozen action tableau. Layered on top of that is a parody of superhero films through the credits that appear on-screen.

Deadpool credits superhero tropes rather than names, subversively pointing out the predictability and interchangeability of the characters in these films. After “Some douchebag’s film” the first credit is “Starring God’s Perfect Idiot”, referring to Reynolds, and really any pretty boy cast as a superhero. “A Hot Chick” refers to Morena Baccarin’s Vanessa, as well as the way most female love-interests are viewed in blockbusters. “A British Villain” refers to Ed Skrein’s Francis/Ajax, and the idea that an accent is often a replacement for a villain’s personality. “The Comic Relief” is T.J. Miller’s Weasel, “A Moody Teen” is Brianna Hildebrand’s Negasonic Teenage Warhead (best name ever), “A CGI Character” is Colossus, voiced by Stefan Kapičić, and “A Gratuitous Cameo” is Stan Lee.

Ryan Reynolds as Deadpool, and Stefan Kapicic as the voice for Colossus (IMDB)

These credits hilariously call out the tropes, but they are also an indication that Deadpool uses the tropes. It doesn’t reinvent the superhero film. In fact, Deadpool is simple and conventional in a lot of ways. The film’s differences mainly stem from its faithfulness to the character, allowing it to include language, violence, and humour that would feel out of place in any other superhero film. But ultimately, just like so many other superhero films, Deadpool is “Produced by Asshats”, “Written by The Real Heroes Here”, and “Directed by An Overpaid Tool”.

The film then opens in media res, with Wade in a cab driven by Dopinder (Karan Soni) on his way to confront Francis. As the opening freeway action sequence plays out, including the crash featured in the opening credits, the film flashes back to fill in Wade’s backstory. Two years earlier, he works as a freelance mercenary based out of Weasel’s bar. He meets Vanessa, a prostitute, and they share an immediate connection. They fall in love and get engaged, but Wade is diagnosed with widespread late-stage cancer. When he receives an offer to cure his cancer, and potentially gain superpowers, Wade agrees in hopes of continuing his life with Vanessa.

He’s taken to a dirty, underground facility run by Francis and Angel Dust (Gina Carano), who torture him to activate his latent mutant abilities. They plan to sell him as a superpowered slave. They eventually succeed in activating advanced mutant healing, which cures Wade’s cancer but makes his skin look like it suffered serious burns. Wade escapes but is unable to face Vanessa in his scarred state. Instead, he becomes Deadpool, a masked figure killing his way through the criminal underworld in search of Francis and, hopefully, a cure for his condition. Back in the present, the freeway action sequence is the closest Wade gets to Francis, but Francis escapes. Francis then hunts down Vanessa, capturing her as bait for a final showdown. With the help of his X-Men friends, Colossus and Negasonic Teenage Warhead, Wade saves Vanessa and kills Francis.

Much of that plot summary sounds conventional, with typical superhero or action film beats. This is by design, because most other aspects of the film are so unconventional. Critics and audiences always cry out for something fresh and new, but some familiarity is necessary to make new approaches palatable. A criticism often levelled against Avatar (Cameron, 2009) is that the plot, basically the story of Pocahontas, was unoriginal. But James Cameron needed a basic, well-known plot structure on which to hang his startling advances in visual effects and cinematography. And so, in every way other than plot, Deadpool is fresh and original. That all begins with the film’s central character.

Before gaining his powers, Wade Wilson is established as foul-mouthed, dangerous, and full of wisecracking, offensive, pop culture-infused humour. But after gaining his powers, he becomes a full-blown, live-action cartoon character. A homicidal, potty-mouthed Bugs Bunny, if you will. He makes cartoon drawings of himself killing Francis, smoke comes off of him after an explosion, he pulls out his underwear to wave as a white flag in an action scene. After he’s stabbed in the head, he sees images of cartoon unicorns as the band Chicago starts playing on the soundtrack.

Morena Baccarin as Vanessa and Ryan Reynolds as Wade / Deadpool (Amazon)

Wade also kills people in silly, cartoonish ways, like with a Zamboni. At the start of the climax, Francis taunts Wade by asking “What’s my name?” Wade replies that he will spell it out for him and then, several minutes later, he literally spells out “Francis” with the bodies of Francis’s men. When Colossus captures Wade and lectures him on being a hero, Wade shatters both hands and a foot attacking Colossus’ steel skin. He then bloodily cuts off his own hand to escape, and sports what looks like a baby’s hand as it grows back. This is a cartoon character come to life, just like in the comics.

He’s a poor version of a superhero at every turn, saying and doing things that most role-model superheroes never would. He takes a cab to two separate action scenes, forgetting his big bag of guns both times. He starts his crime-fighting career wearing a white costume but, when bloodstains become a laundry hassle, he changes to a red suit. He lives with Blind Al, his elderly roommate, in a run-down basement apartment where Wade wears Crocs and passionately discusses IKEA furniture in between bouts of masturbation. He loudly lectures Dopinder to not kidnap and murder his romantic rival, while alternately whispering encouragement. When Vanessa is kidnapped, Wade returns home to have a huge, “fuck”-laden tantrum.

Overall, his main goal is to torture and kill the villain. Colossus acts as the angel on Wade’s shoulder, encouraging him to be a hero and join the X-Men. But Deadpool the character, and Deadpool the film, actively avoids the standard heroic arc. Deadpool kills, tortures, and maims. He never acts out of anything but self-interest. In the finalé, when Francis is defeated and helpless, Colossus gives a speech urging Wade to make the heroic choice. But Wade cuts off the speech by shooting Francis in the head.

The danger of such an over-the-top, violent, vulgar, albeit faithful, approach is that Wade could potentially be unlikable, even if he’s amusing. The filmmakers wisely avoided this trap by using a non-linear structure in the first half of the film. Wade first appears in the freeway action sequence as a violent, offensive, cartoonish character, but the sequence is broken up by several long flashbacks that depict his origin. The flashbacks feature a genuinely affecting romance between Wade and Vanessa, and Wade’s horrific torture at the hands of Francis. These contextualize Wade’s potentially off-putting personality and behaviour by simultaneously demonstrating love for Vanessa and his righteous anger towards Francis. Thus, the film pulls off the tricky feat of making viewers sympathize with an offensive psychopath.

Furthermore, the origin had the potential to be dark and unsettling so it benefits from intercutting with Wade’s later zaniness. The first half of the film has the difficult task of balancing these disparate tones, and the filmmakers succeed beautifully.

Ryan Reynolds as Deadpool and Brianna Hildebrand as Negasonic Teenage Warhead (© 2015 – Twentieth Century Fox / IMDB)

The Wade-Vanessa romance is the heart of the film, and it has surprising emotional weight. The characters meet at a bar and start one-upping each other with increasingly outlandish stories of their terrible childhoods. They have an immediate connection through similar senses of humour. Wade then pays Vanessa to play skee ball with him before they have sex. A lot of sex. A montage of a year’s worth of holiday-themed sex plays out. My favourites are Vanessa dominating Wade for International Women’s Day, and Vanessa and Wade quietly reading during Lent. Wade is a mercenary and Vanessa is a prostitute — because romantic interests in comic book films are typically reduced to objectified sex symbols — but they are clearly perfect for each other in a refreshing, sex-positive way. As Wade puts it when he proposes, “your crazy matches my crazy.”

Reynolds and Baccarin sell the romance, but they also sell the heartbreak after Wade’s diagnosis. These scenes don’t play out like wacky cartoons, they’re taken seriously. Vanessa looks for any way to cure Wade. Wade, meanwhile, quietly makes peace with his fate and plans to leave, sparing Vanessa the heartbreak of caring for him. Vanessa becomes his motivation for everything, for gaining his powers and then for hunting Francis to heal his skin condition. The motivation is credible and relatable because the romance is credible and relatable. In the end, after Vanessa lectures Wade for staying away so long, she accepts him regardless of his appearance because she loves him. It’s less flashy than the action or humour, but the romance anchors Deadpool, and the film would not have succeeded without it.

A lot of superhero films feature romance, if not always this credible and sex-positive. Not a lot of superhero films are this funny, though. Deadpool is funnier than most straightforward comedies. Fox refused to pay screenwriters Rhett Reese and Paul Wernick to be on set, so Reynolds paid their salary personally. Together with Reynolds, they developed riffs and improvisations during filming, punching up the humour at every opportunity. They also benefited from Wade often wearing a full face mask, covering his mouth and allowing the filmmakers to add in extra one-liners whenever they wanted.

Many jokes come at the expense of the X-Men film series or Reynolds’ less successful films. Wade requests that his superhero costume not be green or animated, as in Green Lantern. When explaining the importance of beauty, Wade says “do you think Ryan Reynolds gets by on his superior acting ability?” At one point, Wade says things go horribly wrong and the film cuts to an action figure of Deadpool from X-Men Origins: Wolverine. Francis also threatens to sew Wade’s mouth shut, which Wade insists is a bad idea. Wade riffs with Weasel about his superhero name, trying “Captain Deadpool” before settling on just “Deadpool”. As Weasel puts it, “that sounds like a fucking franchise!”

When Colossus tries to bring Wade to Professor Xavier, Wade asks if it will be Stewart or McAvoy, the two actors who have played the character, before saying the X-Men continuity is confusing. Best of all, when Wade enlists the help of the X-Men, he only finds Colossus and Negasonic Teenage Warhead, who appeared earlier, and he remarks “funny that I only ever see two of you. It’s almost like Fox couldn’t afford another X-Man.”

This leads to the fourth-wall breaking, which is used to great effect. In the first scene, in Dopinder’s cab, Wade finds some used gum, tries to get it off his hand, and it sticks to the camera lens. He soon begins to narrate directly to the camera, welcoming viewers to his film and acknowledging how unlikely it was for Deadpool to get his own movie. In voiceover, he discusses the pros and cons of headlining a superhero franchise. He pushes away the camera before he horribly tortures a bad guy. He calls out a superhero landing before it happens. At one point even Weasel tells Wade to talk to another character because “maybe it’ll advance the plot.” Wade is aware that he’s in a superhero film, allowing him to give a running commentary on the tropes as they happen. This is yet another reason that the conventional plotting works so well, as Wade would not have been able to mock an unconventional plot.

Deadpool was first written by Reese and Wernick in 2009, with heavy input from Reynolds, and was fine-tuned by them over the six years of development. The humour works in part because it’s utterly specific to the sensibilities of these men. Who else would write the hero calling the villain a “shit-spackled muppet fart”? What other writer would have Wade remark upon seeing Negasonic Teenage Warhead in action “I so pity the dude who pressures her into prom sex”? The humour is specific and consistent, rather than written by a market-driven committee, and that shows.

The fight between Colossus and Angel Dust stops briefly when Angel Dust’s breast accidentally pops out of her shirt and Colossus looks away so she can fix it. When Wade leaves for his climactic battle, he tells Blind Al that he hid 116 grams of cocaine somewhere in the apartment next to the cure for blindness. Even during Wade and Vanessa’s emotional reunion, she removes Wade’s mask to find a picture of Hugh Jackman stapled to Wade’s face. The jokes are original, specific and so densely-packed.

The writers did an excellent job, but so does director Tim Miller. It’s Miller who needed to stage the action, balance the tricky tone, and make the film work so well on a relatively low budget. The action is appropriately brutal and visceral, with blood splatter, lost limbs. and even decapitations, but the balance of humour prevents it from becoming oppressively violent. The opening freeway action sequence in particular demonstrates Miller’s inventiveness. Having forgotten his bag of ammunition, Wade has only 12 bullets with which to take out Francis’s men. He flips around acrobatically, counting down the shots as he goes. These are the only bullets fired by the character until the very end. As for the rest of the film he fights with the two katanas sheathed on his back.

The freeway sequence is also indicative of Miller’s frugality. Miller comes from a visual effects background, his company created the entire prologue sequence to Thor: The Dark World (Taylor, 2013) digitally, for example. So, he was an expert at making relatively cheap visual effects look expensive. He also saved money structurally. By breaking up the freeway sequence with extended flashbacks to the origins, one big action sequence seems like three. When Fox reduced the budget at the last minute, Miller and the writers adapted by cutting a motorcycle chase out of the freeway sequence and having Wade forget his big bag of guns for the climax. Despite cutting these action elements, the action is never lacking. Budget cuts forced Miller to get more creative about the action and the film benefits from that extra creativity. Miller made a much leaner, more propulsive film than originally intended, with only the action necessary to serve the plot.

Poster excerpt (IMDB)

The element that makes Deadpool work so well above all else, however, is Ryan Reynolds. For whatever reasons Reynolds felt drawn to this character back in 2004, his performance represents the perfect symbiosis of actor and character. I can’t imagine anyone else playing this role. Reynolds has a natural quick-wit that makes Wade’s humour credible, and his twisted sense of humour feeds into the character. Beyond the humour, Reynolds also sells the violent and romantic sides of Wade just as credibly. The biggest challenge for the film was to balance the humour, romance, violence and serious drama, and Reynolds’ performance is essential to that balance. He holds it all together at the centre.

Also, not many actors would display such a lack of vanity in a big blockbuster-starring vehicle. Reynolds mocks his worst films and his own acting ability. He also spends two-thirds of Deadpool either in a full-face mask or scar makeup. In most films featuring full-masked heroes, Spider-Man or Iron Man, for example, the filmmakers look for any opportunity to show the actor under the mask. Deadpool demonstrates uncommon restraint in that regard.

In the end, Reynolds’ 11-year quest to make a Deadpool film paid off impressively. Deadpool was an enormous box office success. For context, the film earned $132 million in its opening weekend, as much as the total domestic gross of The Wolverine (Mangold, 2013). Ultimately, the film earned $363 million in North America and $783 million worldwide, making it the highest-grossing X-Men-related film by any metric, and that’s with an R-rating and on a much lower budget. Somehow, this silly, violent character from the early ’90s was more appealing to audiences than the entire assembled X-Men. It was also a critical success, earning Producers Guild and Writers Guild nominations that briefly fuelled some Oscar buzz.

A lot of articles at the time focused on the R-rating as the key to Deadpool‘s success, as if audiences had been yearning for a foul-mouthed, violent superhero film all along. But filmmakers such as James Gunn, director of Guardians of the Galaxy (2014), urged studios to take the right lessons from the success. He insisted that Deadpool succeeded because it was original and took risks, not because it had an R-rating.

I believe Deadpool succeeded because it so faithfully adapted the character, narratively and tonally. Deadpool is a more adult superhero than most, with adult humour and adult violence, so the film needed the R-rating to be true to the character. I believe that audiences, critics, and Guilds responded positively because the filmmakers demonstrated a passion for the character and the honesty of vision. They loved this foul-mouthed, offensive, violent killer so much that the world fell in love with him too.

* * *

Stan Lee Cameo Corner

Lee appears as an announcer at the strip club where Vanessa works later in the film. This is hilarious in an “I can’t believe they got a 93-year-old legend to do that” kind of way. That is 25 cameos in 39 films.

Credits Scene(s)

In a parody of the post-credits scene of

Ferris Bueller’s Day Off (Hughes, 1986), Deadpool appears in the same bathrobe and hallway as Ferris to shoo people out of the theatre. He claims that they do not have the budget for a big, impressive post-credits scene with Samuel L. Jackson, but does tease a sequel featuring Cable before ending with a “chicka-chicka!”

First Appearances

• The entire supporting cast, Morena Baccarin, T.J. Miller, Briana Hildebrand, Leslie Uggams, Karan Soni and Stefan Kapičić, all returned for

Deadpool 2 (Leitch, 2018)

• Screenwriters Rhett Reese and Paul Wernick also returned to write

Deadpool 2

Next Time

The Civil War was neither “civil” nor a “war”.

- Provocative and Pioneering: 'Deadpool' Sets the Stage for a New ...

- The Past and Future of 'Sin City' 'Deadpool', 'Alien', 'Predator' and ...

- 'Deadpool' Is, as Trump Would Put It, "Like a Retweet" - PopMatters

- 'Deadpool 2': The (X-)Force Is Strong with This One - PopMatters

- Deadpool 2 (film review, J.R. Kinnard) - PopMatters

- Deadpool Assassin #1 (comics review) - PopMatters

- Deadpool | Official Trailer 2 [HD] | 20th Century FOX - YouTube

- Deadpool (Wade Wilson) | Characters | Marvel

- Once Upon a Deadpool | Fox Movies | Official Site

- Deadpool 2 | 20th Century Fox

- Deadpool Movie (@deadpoolmovie) | Twitter

- Deadpool (2016) - Rotten Tomatoes

- Deadpool - Wikipedia

- Deadpool (2016) - IMDb

- Deadpool (film) - Wikipedia

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)