“CBGB was a unique animal unto itself as the place was a right shithole that had this desolation shithole-row type of charm,” says Walter Lure. “The place stank and was in a rotten neighbourhood, but that was part of its attraction; the anti-glam factor. Punks always fancied themselves as down and out rebels living drugged-out on the edge. Max’s was at the other end of the spectrum. It had been a trendy Warhol gang hangout in the late sixties and early seventies, and really was sort of decadent and glitzy. After the Warhol gang faded away, the punks took over and gave it a bit of street credibility. The place still was a nice-looking club that had a decent restaurant on the ground floor and good music on the second floor.”

Max’s was much more up Suicide’s street with its towering artistic legacy and less self-conscious cliques. Under its next owners and the guidance of Peter Crowley, this would be the club where Suicide’s fortunes changed and they first got on record. But in 1974, it was still a struggle for them to get a foot in the door.

While artists still frequented the front bar, the 30 foot deep back room had achieved an elite notoriety after being adopted by the Warhol crowd in the late sixties. Its low-lit ambience still attracted huge stars and artists behaving badly. Meanwhile, the live room had played host to the Stooges (with Iggy famously slashing his chest after returning with Raw Power) and Dolls. “Us younger kids, like Patti Smith, Wayne County, David Johansen and the fantastic New York Dolls, who were part of the back room, began to have more relevance,” says Elda Gentile. “Max’s focus went to music and the days of Warhol’s dominance began to wane.”

After the Mercer’s collapse, Mickey Ruskin started allowing in more local musicians, such as Patti Smith and Lenny Kaye — who supported veteran activist folkie Phil Ochs in December 1973. Max’s also broke with its policy of only presenting acts signed to record companies by giving Television and Patti a five day stint in August 1974.

Marty and Alan had asked Mickey Ruskin about playing at Max’s a couple of years earlier. Ivan Karp had even sent a letter of recommendation, which prompted a provisional Easter date before Ruskin backed out when Suicide called to con rm. In early 1974, Marty returned and ended up leaving a reel-to-reel demo tape with booking manager Sam Hood, but had still heard nothing after a few weeks. Too impoverished to be flinging reel-to-reels about, Marty decided to go and get the tape back. Sporting his ‘Suicide’-studded jacket, hat, shades, and steel pole, he turned up at Max’s and found Hood in his office.

Marty soon began to feel like a y on Hood’s coffee cup, recalling how “He only seemed to be hiring guys who’d just made records for Sony, and said, ‘I’m sorry, I can’t book you’. So I asked him for the tape back. I sat down, thinking ‘I’m just gonna sit here until he finds the tape’. He started looking for it, going through boxes, but still couldn’t find the tape. I had no other place to go, and I didn’t care, now we weren’t getting a gig. Then, at some point, I started to nod, like having a siesta. All of a sudden, he decided he would give us a showcase. I guess he had been worried about me nodding out in his office. Maybe he thought I was high or overdosing, or something. I sat there and could see what was happening, so I kept it up. To top it off, he walked me to the elevator. He wanted to make sure I got on the elevator okay and wasn’t going to nod out. I don’t know why he was so worried. I did not expect that, but it was like getting out of the army. I walked out and said to Alan, ‘We got a gig at Max’s!’”

The Village Voice ad for Suicide’s Max’s debut on August 6 quoted Roy Hollingworth’s Melody Maker review, one from Variety calling them “the most bizarre act around” and that Village Voice review declaring that they were “the hippest act in town.”

Suicide had been slotted in over a showcase for a major label glam band. In the audience was Craig Leon, another early fan and vital figure in their story. Born in Miami in 1952 and growing up in Florida, where he opened his first studio, Craig would soon become another seminal presence in the downtown revolution, producing debut albums by the Ramones, Blondie, Richard Hell and Suicide. He was already working in the studio assisting producer Richard Gottehrer, who had co-written sixties hits such as ‘My Boyfriend’s Back’ and ‘I Want Candy’. Gottehrer had also founded Sire Records with Seymour Stein in 1966.

Craig had already done some work at Sire when he found out from his friend Paul Nelson (the man who had signed the Dolls to Mercury) that London Records was planning to launch an American branch of Jonathan King’s UK Records in New York, and was looking for an A&R scout. After reasoning “Maybe I’d want that instead of Sire, which was an unknown entity at that time,” Craig went for an interview with “this old school, cigar-smoking kind of A&R guy,” who assigned him to “go around this weekend, then give me a report, tell me what you’ve got. If I like your observations, maybe you can work for us instead of Sire.”

Craig knew his friend Terry McCarthy, whose apartment he was staying at, was managing a band who were also on the same showcase as Suicide that weekend at Max’s. Having long forgotten McCarthy’s band, beyond it being “a Roxy Music-Dolls imitation in high heels,” Craig was about to leave after their undistinguished set, but impetuously decided, “I’m gonna stay and check out this thing called Suicide that’s playing next. There were more people to see the glam band than stayed to see Suicide.”

He was glad he did. Speaking now, Craig’s most abiding memory is of Alan “swinging these chains and hitting the table in the front row. One of the important things about the gig, that I thought was cool, was that he was going one step beyond Iggy Pop. Suicide were the first people in New York who really coined the punk thing. There were by now only about eight people in the audience, and he was swinging these chains and making a big noise with them. Marty was making like loud Velvet Underground walls of noise, but it had rhythm, although not as rhythmic as it became on the album. Alan had his hair up in a do and was wearing something very sixties R&B, like a leopard skin coat or something like that. He was jamming and doing a kind of James Brown thing over it. I thought they were phenomenal, because it was something totally new. I was very aware of the German bands then, and they reminded me of Can, a lot. Not so much Ash Ra Tempel or Popol Vuh, it was a lot more melodic than them. My favourite Can record was Monster Movie. That repetitive thing of ‘You Doo Right’ and ‘Father Cannot Yell’ was kind of like what I thought Suicide was doing that night, in a very New York underground kind of way. Can’s singer Malcolm Mooney was kind of like the Teutonic version of Alan, except he was very restrained in comparison. I really thought Suicide were great.”

Excited at his discovery, Craig hurtled into London Records on Monday morning, enthusing about this group he had seen called Suicide. He told his prospective boss how they didn’t have bass or drums, just a guy playing a keyboard, and another one singing, “except not really singing because it was like hardcore downtown art stuff… I said I thought this band was great, doing something really innovative and new. In my bright-eyed innocence, I thought that something new and different was what the label would be looking for if they wanted a young guy working for them to find new bands. In essence, they did, but they didn’t want them quite that different! Obviously the name wasn’t right for the label, right off the bat. He said, ‘We’ll get back to you, kid.’ I didn’t get the gig, which cemented the fact I was going to stay at Sire, so I ended up not getting a job because of Suicide! I didn’t meet Suicide at that time, I just made a mental note and put them on my list.”

Although Suicide got to play a return gig, as 1974 progressed, Max’s started falling on hard times, exacerbated by three res and the Warhol crowd drifting on to One University Place and the Ocean Club on Chambers Street. In her book High On Rebellion, Yvonne Sewall-Ruskin accuses the glam crowd of taking over the night scene, a move which drove away the more generic arts scenesters who had traditionally patronised the club. “Mickey became bored with his own party. He had filled too many stomachs without filling his own pockets,” she writes. “This combination of factors — the res, thefts, unpaid tabs, and drugs — contributed to Max’s demise.” The club closed in December, marking the end of an era, and one of the most vital artistic hubs of New York’s twentieth century, but it wouldn’t be the last the world heard from the venue.

The winter of 1974 saw Marty forced to temporarily move out of his studio at after Mari had moved in with the whole family, which was then four kids, a cat and a dog. “I had allergies to cats so I split for a while,” recalls Marty. “At first, I went to this freezing little room at the Project where Alan had stayed. Now he was living with his girlfriend in Brooklyn, he gave me the keys.”

By then the main janitor was artist Joe Catuccio, who “wasn’t so happy about seeing one of us sleeping there again. He really liked having that place to himself. Joe used to paint there; these very large, almost modern religious paintings. He was like a Michelangelo of his time. I only stayed there a couple of nights. At night I would go to Max’s. Howie Wolper saw me there and said ‘You gotta come and stay with me.’ He had a loft downtown with his girlfriend, who was Elodie Lauten, the electronic composer. The three of us would sleep on the floor. That kept me going for a while until Mari found another place in Brooklyn.” (Catuccio moved out of Greene Street in 1997 and still operates a Project of Living Artists in Brooklyn.)

Still banned from CBGB and with another club gone, Suicide retreated to the Project to give their sound a makeover. One of Marty’s most momentous strokes in sculpting his fermenting instrumental panoramas was also his most romantic. After Mari had stopped playing drums at rehearsals, he had stuck to his declaration that she would never be replaced by a human, preferring to explore the rhythmic nuances which congealed in the amped-up feedback roaring out of his overdriven organ, or using his one-man-band snare-cymbal combination. Now it had become time for Suicide to introduce a discernible beat, if only to give Alan a firmer platform to grasp as song ideas continued to form in the lyrical phrases he was playing with.

“One night, it just came to me,” recalls Marty. “The perfect idea which was gonna change everything!”

Audacious and Sacrilegious

Get a machine to do the drums.

Now that seems such a natural choice but, in 1975, the very concept of replacing a flesh and blood drummer with a box of circuits was alien, audacious and even sacrilegious. Previously, the United States Of America had sprinkled primitive electronic beats on their epoch-making 1968 debut album, but it had hardly been central to the action. The hissing rhythm box underpinning the murky stratas of Sly Stone’s There’s A Riot Goin’ On in 1971 fitted perfectly (if often dismissed as a product of his coked-out derangement). That year, I witnessed Kingdom Come, the group formed by madcap singer Arthur Brown after the demise of his Crazy World, play a show bolstered by the mechanised percussion of the Bentley Rhythm Ace, manufactured by Ace Tone, the Japanese predecessor to the Roland Corporation. The band’s 1972 album, Journey, was the first whole album to feature entirely electronic drums. Kraftwerk’s mechanical beats, which were introduced as a robotic component on 1973’s Ralf and Florian, after ‘Kling Klang’ on the previous year’s Kraftwerk 2, came from a preset organ’s rhythm box until they started constructing their own.

Marty knew about the rhythm boxes being used by organists at weddings. “I’d always seen these drum machines. Every once in a while you’d get invited to someone’s wedding, or confirmation. Those guys would be playing a keyboard piano or accordion, using a rhythm machine, and they’d entertain the whole house. They couldn’t afford a band so they got one or two people and used rhythm machines.”

These humble, money-saving devices gave Marty a radical new plan to change Suicide’s music from the bottom level up. “I could really see it, like it was visual. It was a whole new depth of space, and concept of arranging, where you could just play with the parts. Bands were pretty much in a format at that point, which was starting to dictate the content. If you really wanna change radically, you’ve got to change the whole thing, the sound of the music itself from its basics, and really get away from it. I didn’t really have that all worked out at first in my head but, all at once, I just had this vision of how cool it would be to try.”

The first stab at inventing a machine to produce rhythms dates back to Leon Theremin’s rhythmicon of 1932 which, after proving too hard to use, lay forgotten until 25 years later when California’s Harry Chamberlin created a machine called the Chamberlin Rhythmate, which was stacked with tape-loop snippets of drumkits playing assorted beats. In 1959, Wurlitzer released the mahogany-housed Sideman, the first commercially produced drum machine, intended to provide electro-mechanical rhythmic accompaniment for its organ range by offering 12 different electronically generated rhythm patterns with speed control, which could combine popular grooves of the day such as the waltz and foxtrot. In 1960, New York-based electronic pioneer Raymond Scott unveiled his Rhythm Synthesizer, followed three years later by a drum machine he called Bandito the Bongo Artist, which he used on 1964’s ground-breaking Soothing Sounds For Baby.

Through the sixties, rhythm machines became more compact than the original floor-standing models, and fully transistorised after home organ manufacturer Gulbransen collaborated with automatic musical equipment company and renowned jukebox makers Seeburg to produce the Rhythm Prince, which was the size of a guitar amp head and used electro-mechanical pattern generators (preceding the Select-A-Rhythm device installed into electronic organs later that decade). The Rhythm Prince became Marty’s first drum machine, after he spotted a second-hand model for sale in the paper, making the journey to Queens to buy it for $30 from a couple whose 19-year-old daughter bought it to accompany her poetry. They told him she had recently committed suicide.

Up until then, Suicide ‘songs’ had been built on Marty’s riffs or chord progressions, which meshed into their own internal pulses, over which Alan sent phrases which coalesced into songs. Now everything changed. “To me, the rhythm was implied in the riff,” explains Marty. “At some of those gigs, when we were still doing pure electronics with the amp, the riff and feedback synched up as a rhythm, without steering it in a more recognisably percussive way like it would have with drums. Once I brought the drum machine in, the propulsion was however I interpreted the rhythm, and whatever it meant to me. What made rock’n’roll always work for me, without even realising it, was that rhythmic energy when I heard a great record.”

While Kraftwerk despised the preset rhythms found in drum machines, so much so that they ended up building their own, Marty embraced them, working flickering Latin-based grooves into new Suicide songs such as ‘Sneakin’Around’, which sees him doctoring Cream’s ‘Sunshine of Your Love’ riff, and ‘Space Blue Bamboo’; the first of many quivering garage and R&B riff mutations. In the middle of a scorching hot summer, which was also New York’s wettest in recent history, Suicide embarked on a rigorous writing and rehearsal regime in their leaking basement under Greene Street.

“That’s where we were spending most of our time,” says Marty. “We were always there. Alan was living there at the time. That was like our home away from home. Our hangout off the streets.” The new drum machine motivated the pair into recording these first experiments on Alan’s two-track recorder, with Marty’s Rhythm Prince and organ going through a guitar amp into one input and Alan’s vocals into the other. After nearly five years in existence, Suicide finally got down to recording their first proper demos, which Marty likes to describe as “ecstatic adventures, part hallucinogenic; a very powerful new sound suggesting all kinds of visions.”

While the yearning ‘Space Blue’ and eerily weightless ‘Speed Queen’ appeared on 1981’s ROIR cassette release Half Alive, along with a spikey missive called ‘Long Talk’, many more emerged as a great lost record when they accompanied Blast First’s 1998 reissue of the second Suicide album. Marinated by time and years in storage embalming this miraculous document like a faded sixteenth century map, the corroded lo-ambience actually adds to the haunting intimacy and ghostly atmosphere of songs such as fifties rock-riff-heisting ‘Spaceship’, techno beat-presaging ‘Creature Feature’, mysterioso organ-draped ‘A-Man’ and masturbating stick insect click of ‘Do It Nice’, where the impact and implications of Marty’s new Rhythm Prince becomes most evident. While the malevolent drone-bed and sparking magnesium riffage of ‘See You Around’ gives an idea how Suicide might have sounded at those early, pre-drum machine shows, ‘Into My Eyes’ (confusingly mis-titled ‘Space Blue’ on Half Alive) is a shimmering prototype for the first album’s ‘Che’, Alan imploring “sweetheart” over Rev’s almost religiously sepulchral organ. ‘C’mon Babe’ blueprints ‘Cheree’ and has to be the source of the “I love you” cooings picked up on at the Mercer by both the Village Voice and Melody Maker.

Throughout these smoky apparitions, Alan’s voice billows like stage-whispered black clouds, a hissing demon on Marty’s shoulder as the keyboards emit sudden bursts of crackling static and dismembered proto-riffs on truly startling outings such as ‘Too Fine For You’ and time-suspending ‘New City’. One of the most striking factors about tracks such as the luminescent ‘Be My Dream’ is that, far from being the shattering assault of legend, here was doo-wop soul and cinematic sensibility, awakening in the telepathy between Alan’s more considered home recording persona and Marty’s melodic tapestries. Although bare wired, shivering and waiting for the train to take it to the next stage, the recordings show that Suicide’s sound was now in place, and also suggested that they could make great records.

Suicide also recorded the prototype ‘Dream Baby Dream’ at New York’s Sun Dragon studio around that time. At that point called ‘Dreams’, it shimmers with a pure glistening soul, sensual rhythm and the kind of innocently simple melody which characterises their best work. Returning to his ongoing sculpture analogy, Marty says “We were really starting now. The carving out process was getting to where there were actual tracks that we could take to record companies as demos to try and get deals. We tried some, but not with any success.”

That same year, Lou Reed released Metal Machine Music. Its four sides of cacophonous feedback mortified his record company and nonplussed the public, although Alan says it’s his favourite Reed album. Whether Lou had meant the album as confrontational artistic statement, or an act of revenge after the disappointingly harsh critical reaction to Berlin, it was the most controversial album of his career. Marty isn’t sure if Lou had seen Suicide at that point, but MMM’s speaker-bleeding barrage was possibly the nearest approximation of what the duo had been invoking at shows for the last five years. Metal Machine Music might even have served as a subliminal aperitif for Suicide’s eventual appearance in the outside world, just by title alone.

At this point, the cogs in the universe would seem to be shifting at full throttle for Suicide (for the moment anyway). Next, they would find themselves back in a familiar spot, but this time the new weapons at their disposal, along with timing, would start to assure them of their place in the metropolis which had previously snubbed them.

The Cerebral Pull

By 1974, the cerebral pull of New York City had proved too much for Peter Crowley to resist. Having been “isolated” in San Francisco since the early seventies, he had missed upstairs at Max’s, the Mercer Arts Center, birth of CBGB and gestation of Suicide. After a thankless stint managing the band which turned into Mink DeVille, he returned to find the city facing bankruptcy and imminent collapse (as did Abe Beam, who was forced to make further cutbacks in services when he was sworn in as Mayor that January).

“New York was sleazy and getting worse by the day, which didn’t bother me any, but it was,” recalls Peter. “When I discovered Times Square in the late fifties, it was sleazy, but the porn was under the counter. You didn’t have everything in your face. The police were square then too, and didn’t know what we were up to. Then the hippies put everything on the street. We all contributed to putting bohemian culture on the front pages of magazines, which was a major error. It was much more fun when the squares were square, and didn’t know anything. I came back around the time of the first CBGB explosion. I had missed the New York Dolls because I was wasting my time in San Francisco, but then I discovered Wayne County at the Club 82.”

Situated at 82 East Fourth Street, off Second Avenue, Club 82 briefly filled the void left by the Mercer and now Max’s, as one of the only downtown venues willing to embrace glam-leaning local bands. It was first opened in 1958 as a lesbian hangout for Anna Genovese, wife of mob boss Vito, who found it handy for his East Village heroin trade. Now operated by two women going by the names Tommy and Butch, the basement bar was famous for being the one venue where the Dolls actually did drag up for a performance, on their April 1974 tour of New York’s clubs. Sylvain recalls “It looked all tropical. The Copacabana goes gay, if you will. The centre of it was the actual stage, like a square. The bar was completely around the stage. We would hang down there.”

Marty, who moved into an apartment on Fourth in 1975, recalls Club 82 as “like an after-hours, underground syndicate-type place from the thirties, and a transvestite club for many years. Somebody got in there and convinced them to start doing shows with the neighbourhood bands.” Tommy was just about able to stomach the Dolls, but Marty remembers her being so “appalled” by Suicide that she screamed at them to stop (“although she would always be perfectly pleasant when I passed her in the street”).

Witnessing Club 82’s glammed up decadence and Wayne County in his long blonde wig and gold lamé bathing suit brought Peter Crowley back into the downtown loop. “When I arrived back in New York it was the first place I went to,” he recalls. “I didn’t know Wayne as a rock’n’roller, only his previous incarnation in the theatre. I ended up becoming his manager. I never expected any commercial success, but somebody just needed to do it. I went to Hilly for a gig and he turned me down. I couldn’t understand it. After three attempts, I asked Wayne if there was something I didn’t know about. Wayne said Hilly was probably mad at him for not getting back to him about doing another CBGB gig. Anyway, he wouldn’t give me a date and I couldn’t figure that out because Wayne was one of the biggest draws in New York at that time. So then I went and did Mothers.”

Resourceful as ever, Peter visited a “very interesting character” he knew in the Village called Mike Umbers, who “was kind of a gangster without a gang, a freelance guy not connected with the Mob but involved in slightly shady businesses.” Peter told him his predicament: “Mike, do you know of a bar where I can put on a show because I have an act that I can’t get booked?”

“Not only do I know one, I know one that owes me money!” replied Mike.

The pair hopped in Mike’s car and drove up to 23rd Street and Eighth Avenue, locating a little bar called Mothers, over the street from the Chelsea Hotel. The place seemed dead on its feet, as Peter recalls, “Apparently, Mike had fronted money for the guy to open this gay bar and it had failed. Mothers was two small storefronts side by side. The first one had the traditional bar down one wall, a jukebox at the back, then a doorway that went through to the second one, where there was a small stage where they had had drag shows or whatever, silly things. Seated in there were a couple of alcoholic old queens, the owner, who also t into that category, and a handsome young Thai gentleman who was the bartender. And that was it. There were no customers.”

Maybe not too politely, Mike informed the owner that Peter would be promoting shows at Mothers. This was another world from the arty dog-shit ambience of CBGB, being more focused on unfettered fun, and also funkier thanks to its jukebox stacked with juicy disco and flamboyant Warren, “the quintessential gay waiter, who would sashay around to disco songs, with the tray held above his head and wait on all the punk rockers. It was a hysterically funny clash of cultures, and yet it worked because everybody loved Warren, and having disco was better than if you’d tried to have a hip jukebox. It was just a totally funny kind of thing.”

Peter made the bold move of putting Wayne on for a week when Mothers opened for business in mid-1975. For a few months, it became a hotspot. “We started off with a bang,” remembers Peter. “It was such a small place that, if I had somebody who drew a few hundred people, then I would have to have them for more than one night. I did Wayne for a week and it was packed. Then everybody came saying ‘Can we have a gig here?’ Blondie, Television, Ramones, the whole CBGB crowd, because they were starved for anywhere else to play. Hilly caused himself all this misery and competition because I never would have even thought to do Mothers if he had booked Wayne. Being forced into finding a venue for Wayne, I made my own. I’m quite willing to admit I blatantly stole all of Hilly’s acts, but I wouldn’t have done it if he hadn’t forced my hand.”

Peter couldn’t steal Suicide as this was while they were banned from CBGB. When they asked for a gig, as they routinely would of any new venue in town, Peter instantly gave them a weekly Thursday residency, starting in October. Most importantly, they were headlining. Having missed their formative shows, Peter only remembered Suicide from seeing them booed by a conservative CBGB crowd the previous June, supporting the Fast. “I was in California when Suicide started out, so I missed the very beginning. They already had a history of opening for various New York bands, essentially to no avail. People would just boo them or walk out. That happened when I saw them at CBGB. When Suicide asked if I would book them as an opening act, I said, ‘No, I won’t book you as an opening act because that obviously doesn’t work. I will give you your own residency. You’re the headliner.’ The first time there were a dozen people, the second time there were 25 people, the next time there were 40 people. It worked very well.”

“Someone told us Peter was booking Mothers,” recalls Marty. “One time I called up and got him on the phone. I didn’t know who he was, but he knew who we were. He gave me a date right away, but said ‘You guys should headline’. Peter was instrumental in the whole thing. He had the mentality and aesthetic to know exactly what was happening. He had an amazing background and had worked in a lot of interesting domains. He never had any doubts about us and totally seemed to know what we were about right away, in a very positive way.”

Suicide enthusiastically took to their residency, commencing the defining stretch of this story, which might have taken a different turn had Peter not spotted something in them which reminded him of his time working the lights for the Velvet Underground nearly 10 years earlier.

“Certainly my having been there at the beginning of the Velvet Underground and similar stuff laid the foundation,” says Peter. “For me, these bizarre acts were always going to be marginal. I had no idea they were all going to be so hugely influential. I was probably very pleased to be part of this elite cognoscenti, but I didn’t think this stuff was ever going to be pop.”

Most importantly, Peter Crowley took Suicide seriously, and treated them with respect. It was now five years since that first show at the Project. At last, they had a real champion in their corner.

Kris Needs is a British author and music journalist. He started writing for seminal fanzine Zigzag in the seventies, becoming editor for five years while writing for NME and Sounds. He relocated to New York in the ’80 then became a DJ-producer in the ’90 and has written several books, including Blondie: Parallel Lives and George Clinton & The Cosmic Odyssey of the P-Funk Empire, also for Overlook Omnibus.

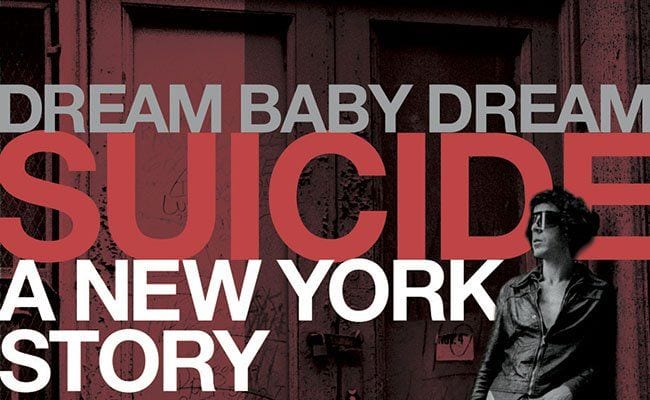

Excerpted from Dream Baby Dream: Suicide – A New York Story. Copyright © 2017 by Kris Needs. Excerpted by permission of Omnibus Press. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)