Rainer Werner Fassbinder was so prolific that, decades after his death in 1982, we’re still rediscovering previously hidden works as they’re restored by the Fassbinder Foundation and making their digital debuts. Criterion has released several of these unearthed gems, including the TV science fiction drama World on a Wire (1973), an early expression of the idea that our mundane reality is a false world, and Volker Schlöndorff’s TV film starring Fassbinder, Baal (1970).

Now comes Eight Hours Don’t Make a Day (“Acht Stunden sind kein Tag“), an epic five-part “family series” (“ein Familienserie“) that runs just over eight hours and uses one family for a kaleidoscopic glimpse of contemporary middle-class Germany. What’s surprising isn’t that it’s so enthralling, but that it’s so good-humored, optimistic and even idealistic. Those familiar with Fassbinder’s output know that he rarely made a film that doesn’t end in death, or at least emotional devastation. Perhaps his most optimistic feature, Ali, Fear Eats the Soul (1974), places the triumph of love in a hospital room for what’s not exactly a slap-happy conclusion.

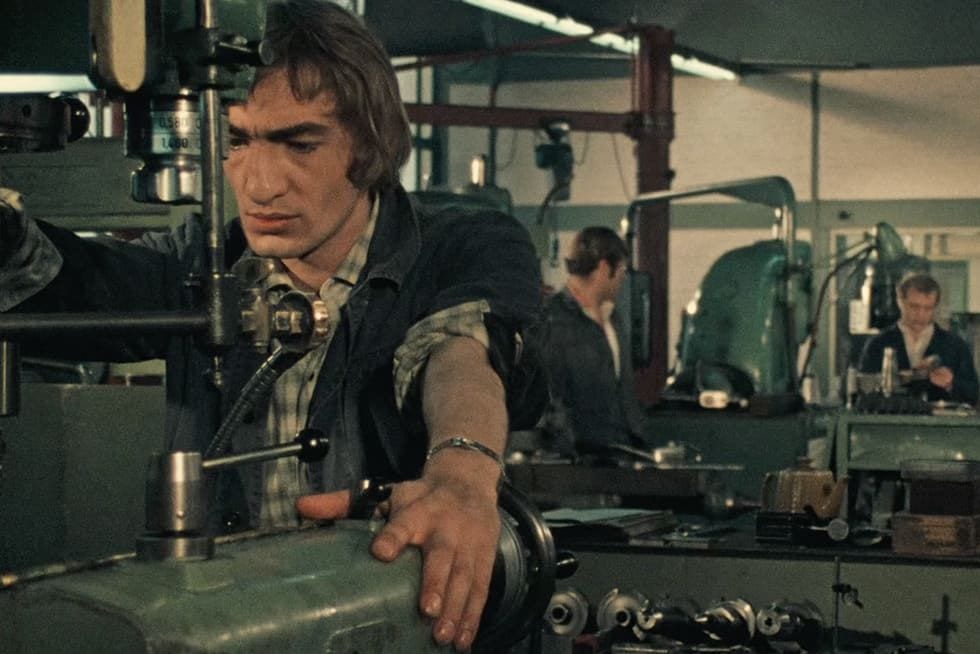

Yet here we have a TV serial in which, radically unlike his more famous serial Berlin Alexanderplatz (1980), he rewards his characters by letting them achieve what they’re working for — and “work” is the key word. The title refers to the working day, and the dominant theme besides love and family will be work itself, its conditions and problems, how it creates social classes, and how people who combine their strengths can work together to improve their lot despite a great deal of resistance from above, from “the way things are” and from within the barriers in their own minds.

Fassbinder’s optimism isn’t cock-eyed but beady-eyed. In the first scene, a family birthday party, two different people are slapped and a multiplicity of bickerings erupt. People will be slapped throughout the series — a social convention observed by Fassbinder not impassively but anthropologically — and the family will never stop arguing among themselves. Slap-happy indeed. This sounds like the makings of a glum plod on evil and the uselessness of life, but not so, far from it. Instead, the series of small and large triumphs snatched from the teeth of social inertia, even entropy, leaves one elated at human potential. This is Fassbinder’s version of a “feel-good” film.

As the writer and director, Fassbinder is speaking personally, for he was still in the first phase of having bulldozed his way into establishing himself as a theatre and film director by doing what he wanted without taking “no” for an answer, even after being rejected by film school. His tireless success in writing and staging plays with a loyal repertory of artists, who then followed him into cinema, led to making connections with WDR, West Germany’s public broadcasting station, as it was offering opportunities to young filmmakers of what would be called the New German Cinema. Fassbinder ran with it.

After starring in Baal, his TV projects were 1970’s The Coffee House (and where is this?) and The Niklashausen Journey, then 1971’s Rio das Mortes and Pioneers in Ingolstadt. In 1972 came the shot-on-video Bremer Freiheit, about a woman who poisons everybody (and where is this?), and this freshly exhumed serial, released by Arrow Video in the UK and now in the US by Criterion. Any random five minutes tells you how Fassbinderian it is.

Here is Dietrich Lohmann’s camera twirling and swirling around the room, panning across every face, suddenly zooming into a closeup on a seemingly irrelevant bystander who observes all from a dramatic distance, just as Fassbinder would continually ask us to stand back, like his idol Bertholt Brecht, and analyse the meaning of what we see. Now and then, we even get a god’s-eye-view from above, whether its meaning is to emphasize the isolation of one character or the unity of many is for you to decide.

Here are the familiar Fassbinder faces, whether in starring roles or dropping by around the edges for a cameo. Here are their characters getting drunk in bars while major American records play on the jukebox — Janis Joplin, Velvet Underground, Elvis Presley, Little Richard, Neil Young, Leonard Cohen and others whose clearances must have cost a pretty penny, making us wonder how this project can make a profit. Even in its seemingly accidental details, how to profit and who gets the money is foregrounded in this series.

The events are structured around a series of couplings. Tall, swaggering Jochen (Gottfried John), who makes tool parts in a factory and whose face becomes all mouth when he smiles, brashly hooks up with the quieter, more thoughtful Marion (Hanna Schygulla), who works in a newspaper’s classifieds section. Although he comes on like he knows the answers, her middle-class mind will prove gently instructive as she draws him out on the subject of work.

Just as abruptly as Jochen picks up Marion at a vending machine, his Grandma (Luise Ullrich, a major Austrian star of the ’30s) annexes to herself a slightly doddering Gregor (Werner Finck, a legendary cabaret comedian), whom she happens to sit beside in a park where he’s reading Lady Chatterley’s Lover. Before he understands what’s hit him, she’s corralled him into hunting for an apartment together. Grandma (“Oma“) is hands-down the most delightful character. Almost everything she says is funny, as is her manner of delivery, and she plays perfectly off of the more phlegmatic but clearly tickled Gregor.

More than a spunky grandma type (though she serves as that), she’s the wily soul of scheming, making do and getting by, determined to manipulate things for her convenience. If she didn’t have a kind and caring soul, she’d make a terrifying dictator. She knows that things are arranged against her, and she must seek the advantage. Her most heartening victory occurs in the second episode, when we can hardly believe her chutzpah in deciding that an abandoned library building, for which the city has no plans, should be converted into an ad hoc kindergarten for the neighborhood kids. When the police step in to put the kibosh on her unlicensed enterprise, the chorus of neighborhood housewives organize a committee to bring pressure on City Hall.

Jochen defends her by saying those who take action are always right, which is an interesting philosophy. It might depend on the action, but he’s concerned with how his factory manipulates his co-workers unfairly. Even with Marion’s prodding, it takes him a great deal of effort to think because, as one of his colleagues observes, it’s hard when you’ve never had to think before, but they’re stumbling their way, amid arguments and setbacks, to organizing and making their wishes known to management.

We watch again and again with held breath as efforts to buck the system, or at least remodel it, seem doomed to failure — but remember, that wasn’t Fassbinder’s experience with the system. In his own way, he was perhaps an Übermensch, but one who, like Grandma, believes in encouraging and organizing people to work for their own advantage. He projects his optimism not from a context that “everything’s all right in this best of all possible worlds” but from the sense that “everything’s shit” and we’ll have to work hard and smart to change it. When the odds are against you, you need that kind of moxie, vision and teamwork, and it helps to remember that, as far as the powers that be are concerned, ultimately you are aligned with the other despised “outsiders”.

Fassbinder was putting nothing less than “positive thinking” propaganda into German living rooms, a very different take on what might be called “mein Kampf” (“my struggle”) for a country still coping with its legacies: the World Wars, the “economic miracle”, the division with the East. His point of view is on the side of “workers” or “the little people”, as perceived by a non-doctrinal quasi-Marxist artist who sees his fellow’s flaws all too clearly. He continually displays the ugly prejudices and assumptions of sex, race, class and ethnicity that flower amid his people, and he implicitly argues that these things must be recognized, and that the best way to deal with them is to raise everyone’s level together.

The serial’s politics are serious, yet it wears them lightly and subversively in the form of crowd-pleasing soap opera. This is the lesson he’s learned from such Douglas Sirk films as All That Heaven Allows (1955), which he essentially remade as Ali, Fear Eats the Soul. When his characters discuss serious political issues and contradictions, these topics aren’t abstractions. They discuss what has a direct bearing on their lives — how much they can pay, whether they must move, whether they should marry, whether they are happy and to what extent that matters, and how much they should be resigned to the insight that when you work, you’re only working partially for yourself.

The other couples are Jochen’s argumentative parents (Anita Bucher, Wolfried Lier), who are perceived as traditional, and Jochen’s suffering sister Monika (Renata Roland) and her martinet husband Harald (Kurt Raab), whose composition beside a portrait of a Kaiser-life figure associates him with the most old-fashioned and intolerable mindset that must be left behind. The petit or rather petty bourgeois Aunt Klara (Christine Oesterlein), who gets along with nobody, is associated at a distance with Marion’s snooty co-worker Irmgard (Irm Hermann), who finally begins to loosen her posture when she picks a boyfriend from Jochen’s gaggle of co-workers.

Those co-workers are played by Wolfgang Zerlett, Wolfgang Schenk, Herb Andress, Rudolf Waldemar Brem, Hans Hirschmüller (his character faring much better than in Fassbinder’s 1971 The Merchant of Four Seasons), Karl Scheydt, and Grigorios Karipidis as an Italian guest-worker whose treatment recalls the filmmaker’s 1969 Katzelmacher, but again with a more enlightened outcome. Rainer Hauer plays their supercilious boss while Peter Gauhe is a resented foreman who turns out to be a mensch. Hanging around the edges of the factory, with no lines and no credit, is presumably a Moroccan guest-worker played by El Hedi ben Salem, who would star in Ali, Fear Eats the Soul. The camera keeps picking him out, as would Fassbinder in real life.

His co-star in that film, Brigitte Mira, shows up here as Marion’s mother, whose unexplained illness necessitates long stretches away from her family, including her young son. That parallels Fassbinder’s own upbringing while his mother had tuberculosis. Fassbinder’s mother is Lilo Pempeit, who appears among the housewives along with Fassbinder regular Margit Carstensen. Also dropping by briefly from his recognizable repertory are his protégé Ulli Lommel as Marion’s old boyfriend, Katrin Schaake as a landlady, Eva Mattes as a tipsy lady, and Klaus Löwitsch as the factory bigwig. Legendary silent star and dancer Valeska Gert has a crazy cameo as a substitute grandma.

The two extras are a retrospective with Schygulla and several others, in which they discuss how the series was both popular and controversial, and an appreciation by scholar Jane Shattuc. Moira Weigel’s booklet mentions that Fassbinder originally wrote eight parts and intended to head into darker directions, but the final three episodes to be filmed for the next fall were scrapped by WDR executives who felt they had a success as is and didn’t want to spoil it.

Those with no knowledge of Fassbinder will find this an engaging serial, while prior fans will be more or less astounded to recognize his signatures within an “accessible” and easy-going enterprise. Every new piece we discover of his output surprises us while also fitting effortlessly into his distinctive work. This serial might make us wish he’d done even more TV, but then, he did a tremendous lot of work already.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)