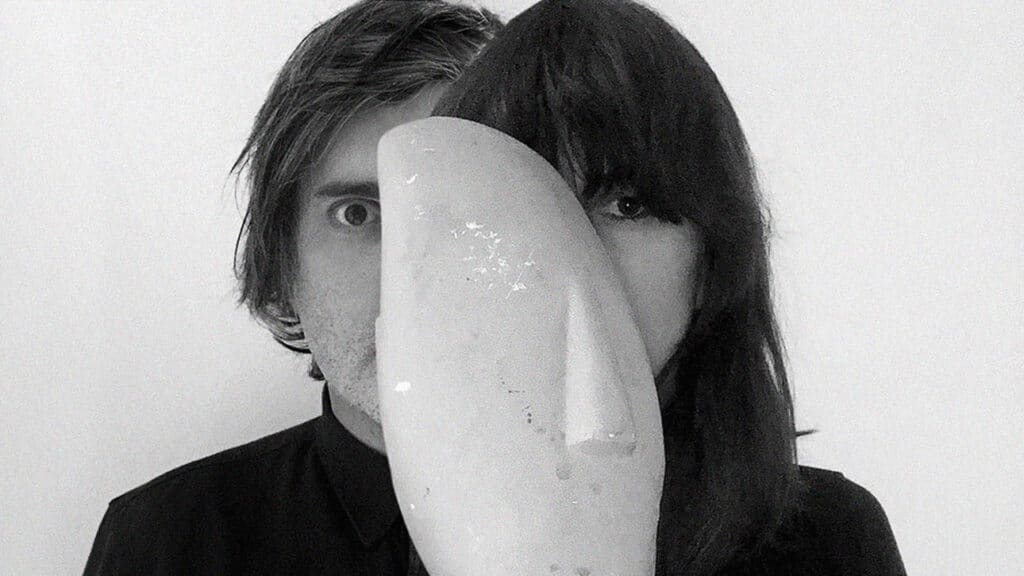

Few contemporary indie bands need to be boosted by critics more than the Fiery Furnaces. A brother-sister duo who came along a few years after the fake brother-sister duo of Jack and Meg White, Matthew and Eleanor Friedberger made DIY music that sometimes sounded like misbegotten classic rock, sometimes like avant-garde indie, and sometimes like something utterly sui generis. In early photographs, Matthew comes across as a kind of alt-rock Chris Eigeman who has fallen on hard times since the last Whit Stillman film, while Eleanor is stylish and striking, somehow evoking both the scrappy cool of Patti Smith and the studied elegance of a fashion model.

The critical response to the Fiery Furnaces’ first two albums, Gallowsbird’s Bark (2003) and Blueberry Boat (2004) bordered on the reverential – yet even these glowing reviews betrayed a certain defensiveness. There was a sense that this band was too self-indulgent – they were incapable of sustaining a single idea for more than 75 seconds at a time, reveled in lyrical obscurity, and, in dozens of small ways, dared the listener to dislike them. Rehearsing My Choir (2005), an album that prominently featured their elderly grandmother, did little to change these perceptions. By the release of Widow City in 2007, the Fiery Furnaces seemed like the kind of band that might require a permanent asterisk in their descriptor.

Widow City is a prime example of a peculiar genre – what might be called the surreally discontinuous concept album. Concept albums in popular music tend to be traditional in their narrative structure, modeled on familiar forms like the memoir (e.g., Kendrick Lamar‘s 2012 album, Good Kid, M.A.A.D. City) or a Broadway show (e.g., 1993’s Tommy or 2010’s American Idiot). Widow City belongs with stranger creations like Brian Eno’s Taking Tiger Mountain (By Strategy), works that resemble experimental fiction more than best-selling novels. You can easily imagine the lyrics of Widow City produced by some Oulipian strategy or emerging out of a sustained engagement with the work of César Aira and Kōbō Abe. An explanatory note on the Fiery Furnaces’ Bandcamp site even alludes to James Merrill’s 1982 crackpot epic poem, The Changing Light at Sandover:

The lyrics were written by means of a method derived from… a mention of Scripts for the Pageant [the third book of Merrill’s trilogy] in an article in the Windy City Times. What this means is as follows. Between seven and eight in the morning the brother in the band would pretend to ask a Ouija board what his sister would like to sing about. He would then pretend that the Ouija board gave him various answers. After this was accomplished he would pretend to write the answers down.

The tone of this note – a simultaneous display and disavowal of seriousness – is characteristic of Matthew Friedberger. His tendency to snark and self-sabotage aligns him with the previous generation of American rock musicians – Paul Westerberg and Stephen Malkmus, for instance – but also with more distant predecessors like Frank Zappa, whose influence Matthew has denied every bit as persuasively as Dan Bejar denies the influence of David Bowie.

Eleanor Friedberger is a different matter. After the band’s final album, I’m Going Away (2009), she started her solo career with Last Summer (2011), a masterpiece about the irreversible lostness of the past and the inescapable sadness of memory. Her subsequent records communicate more directly, with a complete lack of snark and self-sabotage. (Songs like “Roosevelt Island”, “My Mistakes”, and “He Didn’t Mention His Mother” are as good as anything the Fiery Furnaces ever did.) Although the liner notes to Widow City tell us that Matthew wrote all the music and most of the lyrics, the album is clearly a joint creation. Eleanor’s vocals serve as a counterweight to her brother’s insularity: she has the uniqueness of timbre that distinguishes great singers from good ones and a dexterity of phrasing that aligns her as much with the most fluent rappers as with any of her indie rock peers.

Widow City confirms an aesthetic principle – that experiments tend to work best when they have an underpinning in the popular. Think of the detective story that underlies Joseph McElroy’s exacting 1974 novel Lookout Cartridge or the science fiction plots of Andrei Tarkovsky’s sci-fi films Solaris (1972) and Stalker (1979). The first such element in Widow City is its grounding in classic rock. (I am tempted to use scare quotes, but the reader will know what I mean.) Admittedly, Robert Christgau could already discern in Gallowsbird’s Bark the “Most intriguing use of roots riffs in an eclectic context nobody comprehends (including them)” – but Widow City brings those riffs much further to the foreground and creates what Zora Neale Hurston once called a “familiar strangeness”.

This is particularly evident in the album’s three longest songs. “The Philadelphia Grand Jury” is an audacious opening, reminiscent of its dramatic juxtapositions of “Quay Cur” or the title track from 2004’s Blueberry Boat. Two themes jostle against each other – one rhythmic and syncopated, the other swooningly melodic – and shift from instrument to instrument for seven minutes, leading to a song that is catchy moment by moment and yet inscrutable.

Look at this combination as a statement of intent. The lyrics strike a similar balance, with ominous lines like “Make sure that they notarized my will / Make sure Mom don’t look at the news” never quite cohering into the hardboiled narrative they promise. There is a fascinating story here, but one that Matthew Friedberger and the spirits of the Ouija board are choosing not to share. Instead, the classic rock heft of the music overrides our demands for sense, even as the eccentricity of the arrangement forces us – in a friendly kind of V-Effekt– to remain conscious and critical.

“Clear Signal from Cairo” takes a similar approach, augmenting its lumbering riff (dinosaur rock indeed) with a headbanging middle section worthy of Black Sabbath. One is tempted to say that the riff is that signal from Cairo, blasting across continents at the beck of the speaker’s desire. Meanwhile, “Navy Nurse” combines equally heavy guitar and an overloaded rhythm section with a swaggering vocal from Eleanor. There are repeated (and weirdly anthemic) lines about “Last year’s champion dwarf marigold” and an offhand mention of a moonshine called Old Uncle Zeke. The overall effect – a pleasing one – is of a prog band that is not particularly skillful on their instruments and has never read Tolkien.

These overtones serve a complex role. On the one hand, they reflect the band members’ tastes. When Eleanor listed her favorite music for The Quietus, Rolling Stone-approved landmarks like Led Zeppelin’s Houses of Holy and Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks coexisted with more esoteric works like Chris Cohen’s Overgrown Path. Matthew also spoke of his youthful taste for “so-called classic rock”, centered on Pink Floyd and the Who. Yet I suspect a more complex motivation, given his instinctive (and infamous) contrarianism. His embrace of classic rock may be related to a phenomenon I think of as the Great Pitchfork Repudiation, that movement away from a particular brand of aesthetic one-upmanship and toward a frank celebration of diverse genres and artists on their own terms – as species in an ecosystem, one might say, rather than as boxers or basketball teams in a hierarchy. To champion such obvious music can be seen as a clever two-step, a way to antagonize the hipsters and out-hipster them.

The other popular element is harder to describe. We might refer to these songs as Multiverse 45s – tracks that do not have the slightest prayer of being hits on this Earth but might sell millions of copies in a world that has undergone a few tweaks. “Duplexes of the Dead”, for instance, is bluesy and streamlined, with Eleanor (in character) telling us about an uncanny incident during which her husband “sat still / With a look in his eyes and a pen in his left hand,” frozen in anticipation of some otherworldly communication. The details of the transmission are obscure.

The next track, “Automatic Husband”, does not clarify matters much – but the hooks are unmistakable, particularly Eleanor’s pronunciation of “I” as a kind of suspenseful wind-up to each line. In the even more infectious “My Egyptian Grammar”, the same character has been summoned by a “netherworld entity” to communicate… something. The track is emblematic of the approach to narrative on Widow City. A puzzling experience whose reality is uncertain announces emphatically that it has meaning, but the meaning is elusive, and the usual paths to interpretation are compromised – arbitrary (why is the “grammar” Egyptian?), anachronistic (the ancient Egyptians had no word for “motorcycle”, even the most unorthodox scholars agree), and deeply intimidating (one of the relevant hieroglyphs is on page 5566). What turns this lesson in epistemology into a Multiverse 45 is the chorus – a catchy refrain that repeats but with small changes, like a folk song in a kindergarten classroom – and a lovely synthesized string fade out over a quasi-martial rhythm.

“Japanese Slippers” is a similarly rollicking track, fit for a vaudeville hall, about a peculiar domestic arrangement in which the speaker and one “Geraldine” want to spend time alone, presumably for sexual purposes, but creepy “Mr. Raymond in his Japanese slippers” always comes “creepin’ in”. (The word creep does double duty here.) The overtones are of a cult or a compound, with Mr. Raymond the charismatic but unsavory leader who makes unwarranted claims from his disciples.

Mr. Raymond may be connected to the titular subject of the album’s most irresistible song, the slinky, funky “Ex-Guru”. Between Eleanor’s slippery cadences and the tightly interlocking rhythms – reminiscent of “deconstructed disco” or the Clavinet-based early 1970s – one could easily imagine the single finding a place on alternative radio in the era before streaming, back when PJ Harvey’s “Down by the Water” and Beck’s “The New Pollution” could become modest hits.

Beyond these more accessible songs, the rest of Widow City is eclectic to the point of perversity. “Uncle Charlie” sounds like 1980s hardcore, with its preposterous lyrics reflecting the mental muddle of the eponymous uncle:

Was I a senior junior appraisal appraiser

at Mistie’s Auction Hut in Centereach?

Or was I a low-level high-level appraiser of appraisal

at Snugaby’s Crazy Quilts and

Collectibles Collection in Hempsted Hollow?

I can hardly remember

“Right By Conquest” has a sinuous sound, evocative of Middle Eastern music, most likely by way of the aforementioned Led Zeppelin. “Restorative Beer” begs to be sung in bars, the way Americans in commercials sing “Sweet Caroline”. (The dozen or so syllables that Eleanor devotes to the word “restorative” descend exhilaratingly, as if on a melodic zipline.) “Wicker Whatnots” is a collage of incommensurate styles, one of those “ADHD Frankensteins” of which Nitsuh Abebe complained. It is most notable for the way it develops the theme of the sudden and puzzling apparition of meaning – in this case, a “cherub ten cubits high” glimpsed in one’s periphery, with a guitar line shadowing that vision like a leitmotif in Wagner. And “Pricked in the Heart” is simply beautiful, prefiguring some of the prettier tunes on Eleanor’s solo records. Her trademark Sprechgesang has never sounded better – as nimble as Andre 3000 and heart-wrenching as Karen Carpenter.

Just as not everyone wants to peer into Wes Anderson’s cinematic dioramas, so not everyone will warm to this peculiar piece of conceptual art. To listen to Widow City is to enter a musical world that creates its own criteria for judgment. A song like “Cabaret of the Seven Devils” – about a Duke dissatisfied with “what passed for diversion at the Carnival Palace of Don Diego de Cardona” – is a sort of musical platypus, impossible to fit neatly in any preexisting category.

Similarly, the title track seems to be on the path to becoming one of those relaxed, ruminative songs that send a listener away from a classic album – think “Find the River” or “Caroline, No” – but instead disintegrates into something chaotic and abstract, with the drums battering out an uncountable rhythm and the piano banging and clattering in accompaniment. The lyrics become increasingly incomprehensible, even as the music loses its coherence, and one exits the album as one entered, in medias res, with nothing resolved and nothing explained.

Despite “making every single unreasonable demand” – to borrow a phrase from “Duplexes of the Dead” – Widow City remains the Fiery Furnaces’ finest album. Its relative neglect brings into focus a certain glitch in the critical system. Groups that achieve early success are often locked into a narrative of decline, regardless of their subsequent output. Although this is driven by the salutary urge of critics to find new things to say and new artists to say them about, such an approach almost guarantees that a great mid- or late-career album will require reappraisal down the road.

To underestimate Widow City would be to make the same mistake many listeners made with Bob Dylan’s Nashville Skyline (1969), Al Green’s The Belle Album (1977), and Belle & Sebastian Dear Catastrophe Waitress (2003). Widow City expresses the sublime contradictions at the heart of the Fiery Furnaces – the unstable (and ultimately unsustainable) interplay of Friedberger and Friedberger.

Works Cited

Abebe, Nitsuh. “Widow City“. Pitchfork, 10 October 2007.

Christgau, Robert. “The Fiery Furnaces”. Robert Christgau: Dean of American Rock Critics. (ud)

Dahlen, Chris. “Blueberry Boat: The Fiery Furnaces”. Pitchfork. 13 July 2004.

“Epic Theater and Brecht: The ‘V’ Effect“. BBC News. (ud)

Fiander, Matthew. “The Fiery Furnaces ‘Widow City’ Pokes It with a Stick”. PopMatters. 8 October 2007.

Ged M. “The Fiery Furnaces: Eleanor and Matt Friedberger” SoundsXP. 26 April 2004.

Hurston, Zora Neale. Their Eyes Were Watching God. Harper & Row, 1990.

Kaill, Gary. “Personal Records: Eleanor Friedberger’s Favorite Albums”. The Quietus. 27 January 2016.