Ad Astra is a marketing executive’s nightmare. While there are several spectacular set pieces and the script is reasonably smart, it lacks the escapist thrills of a good sci-fi actioner and the cerebral existentialism to woo the arthouse crowd. The big attraction here is a fantastic performance from Brad Pitt, who stars as a stoic astronaut dispatched to Neptune in search of his father’s derelict spaceship. It’s the astronomical humanism of Interstellar mixed with the morose nihilism of Apocalypse Now, fueled by a booster rocket of daddy issues.

Using the loose narrative framework of Joseph Conrad’s novella,

Heart of Darkness (which Francis Ford Coppola famously used as the loose narrative framework for his masterful Vietnam epic Apocalypse Now), writer-director James Gray finds a new way to tackle the melodramatic territory of a tortured son dealing with the collateral damage of an unfeeling father.

Gray navigated similar terrain in 2016’s

The Lost City of Z, in which his obsessive hero makes a harrowing journey into the deepest jungles of Brazil to find psychological closure. (And treasure!) He’s clearly a thoughtful filmmaker, more interested in human behavior than mindless action. As such, Ad Astra – Latin for “to the stars” – is less a glorious exploration of deep space than a sojourn into deep psychological pain.

Most of the film’s external spectacle and internal turmoil is illustrated in a bravura opening sequence. Pitt (as the impenetrable astronaut Roy McBride) calmly tethers himself to the massive International Space Antennae orbiting the Earth and sets about making repairs. Roy, who’s dispassionate voiceover is a constant companion throughout the film, reveals himself to be a man more comfortable in the vacuum of space than the embrace of humanity. Roy’s heart rate has never exceeded 80 beats per minute, even during the rigors of space flight. Indeed, has mastered the art of detachment; a psychological balancing act that keeps him alive in space and estranged from his wife (Liv Tyler as ‘Eve’) on Earth.

Suddenly, an electrical surge bombards the Antennae. Roy listens helplessly to the screams of those trapped inside. He eyes the Earth below, hesitant to untether himself from the array even as it crumbles around him. Gray and his special effects team create a disorienting storm of chaos similar to that of the space station destruction in Cuarón’s 2013 sci-fi opus

Gravity. Chunks of debris and jettisoned humanity plunge from above and then spin into oblivion.

Roy feels nothing.

Brad Pitt as Roy McBride (IMDB)

“I see myself from the outside,” he observes. He has spent his entire life avoiding attachments and “looking for the exit”. Though he seems content to perish on the Antennae, Roy reluctantly detaches himself and parachutes back to Earth. Something draws him back to the planet’s grasp, even if he doesn’t yet know what it is.

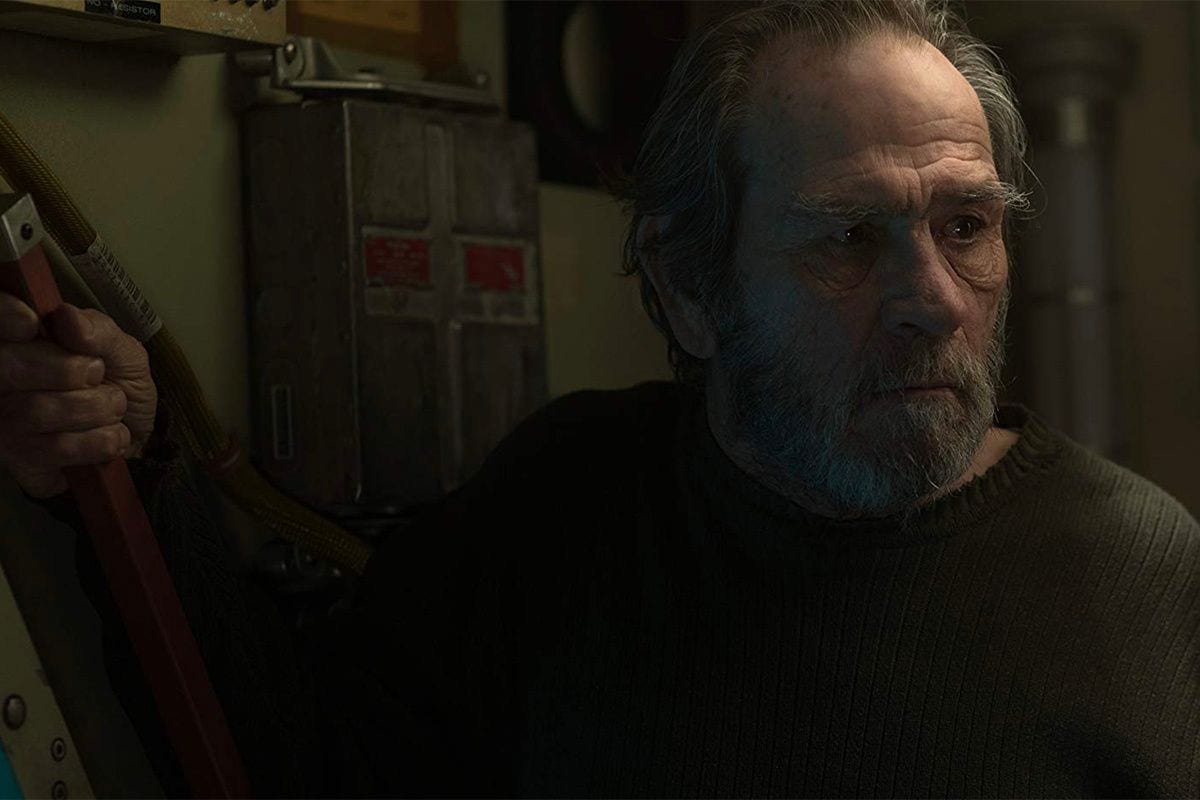

His father (Tommy Lee Jones as Clifford McBride) felt no such sway to Earth’s gravity. In his unflagging quest to contact extraterrestrial life, Clifford and his team boarded a spaceship for Neptune over 29 years ago and never came back. Roy is left behind to obsess over the cold detachment of his father; a religious man who sought evidence of God’s Divine Plan in the form of alien intelligence. It’s a rich religious subtext that Gray, unfortunately, leaves largely untapped until the film’s concluding moments, when he spells it out with a staggering lack of subtlety.

The source of the electrical pulse that destroyed the International Space Antennae is traced to an anti-matter reaction near Neptune; the same anti-matter used to fuel Clifford’s spaceship. The continued electrical disruptions pose an imminent threat to life on Earth. If an incommunicado Clifford is still alive and generating those pulses, the military is obliged to terminate his command with extreme prejudice.

What remains of Ad Astra is Roy’s psychological journey into his own seemingly inescapable fate. He is not only the caretaker of Clifford’s universal reputation of a hero, but the errand boy sent to kill him. As the distance from Earth grows and the pull of his father intensifies, Roy recognizes the dark precincts within himself; the suppressed rage, the fear of emotional commitment, and the resentment of having a father who chose the void of space over his own family.

Like the story structure of Apocalypse Now, there are disturbing adventures along Roy’s voyage into the heart of darkness. A visit to the United States Moon base, for instance, provides an excuse to have a Moon buggy chase with marauding space pirates. Roy must take an eerie swim through a submerged Martian canal to find the launch pad for his spacecraft. There’s even an unplanned visit to an adrift animal research vessel that goes terribly wrong.

Tommy Lee Jones as H. Clifford McBride (Photo by Francois Duhamel – © Twentieth Century Fox / IMDB)

Sadly, these action intervals feel more like calculated diversions than integral insights into the nature of Clifford’s madness and the fate that (possibly) awaits Roy. While Gray executes each of these scenes with maximum precision, seamlessly blending special effects with Hoyte van Hoytema’s stunning cinematography, they never accumulate into a palpable sense of dread. By the time we reach Brando’s wacked-out commando in Apocalypse Now, the tension is almost unbearable.

When Roy finally reaches Neptune, we feel only a sense of relief that his interminable introspection is over. In space, no one can hear you scream, but apparently they can hear you whine.

Gray’s on-the-nose thematic repetitions border on the monotonous. At one juncture, Roy intones, “the son suffers the sins of the father”, as if the audience were too dense to understand the family dynamics he’s been describing for the last hour. Were it not for Pitt’s steadying presence, Ad Astra might crumble beneath its own dramatic pretensions.

Thankfully, Pitt is damn good in this role. Understated and hermetically sealed, Pitt keeps his Hollywood charm buried until the appropriate moments. When he seizes the controls of a crashing spaceship, you just know he’s going to land it safely. More importantly, when he paces the room trying to regain control of his careening emotions, you fear he might crash. Pitt is asked to carry the entire film and the result is one of the best performances of his career.

Ad Astra succeeds as mildly entertaining ‘soft sci-fi’, even if it fails to land a substantial existential punch. For those jollies, you can always check out Claire Denis’s vastly superior space saga from earlier this year, High Life. Still, if you’ve ever felt like your parental conflicts are cosmically complex, Ad Astra might just provide some needed perspective.

Now that Pitt, George Clooney (Solaris, 2002), and Matt Damon (The Martian, 2015) are all veteran astronauts, it also opens the door for an Ocean’s Eleven crossover film… in space! Do you want to call Steven Soderbergh or shall I?

- 'The Martian' on Blu-ray: An at-Home Lesson in DIY Space Survival

- What if an Astronaut Was Stranded on Mars? - PopMatters

- 'The Martian' Does the Math - PopMatters

- Warming Up to Melody: An Interview with Film/TV Score Composer ...

- 'Solaris': Moral Hazards on a Soviet Space Station - PopMatters

- Denis Goes for Broke with Hallucinatory High Life - PopMatters

- High Life, Claire Denis (film review) - PopMatters

- Seeking El Dorado Is Its Own Reward in 'The Lost City of Z ...

- Class and Classicism: An Interview With James Gray of 'Lost City of ...

- In Film as in War, There's What Remains in Its Wake: 'Apocalypse ...

- Apocalypse, American Style - PopMatters

- Christopher Nolan's 'Interstellar' Does an Amazing Thing With Corn ...

- The Science Overshadows the Story in 'Interstellar' - PopMatters

- 'Ad Astra' Says Goodbye to the Great White God - PopMatters

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)