Robert Siodmak has had at least four distinct phases as a filmmaker, and the only one fairly represented on disc is the third phase, when he became a master of Hollywood noir thrillers like The Spiral Staircase (1945) and The Killers (1946). His first career in Germany’s late Weimar era, his second career in France, and his fourth career in postwar Germany are lamentably under-represented on Blu-ray. Kino Lorber has just issued one example each from his Weimar phase and his postwar phase, and they make a good start for deepening our understanding.

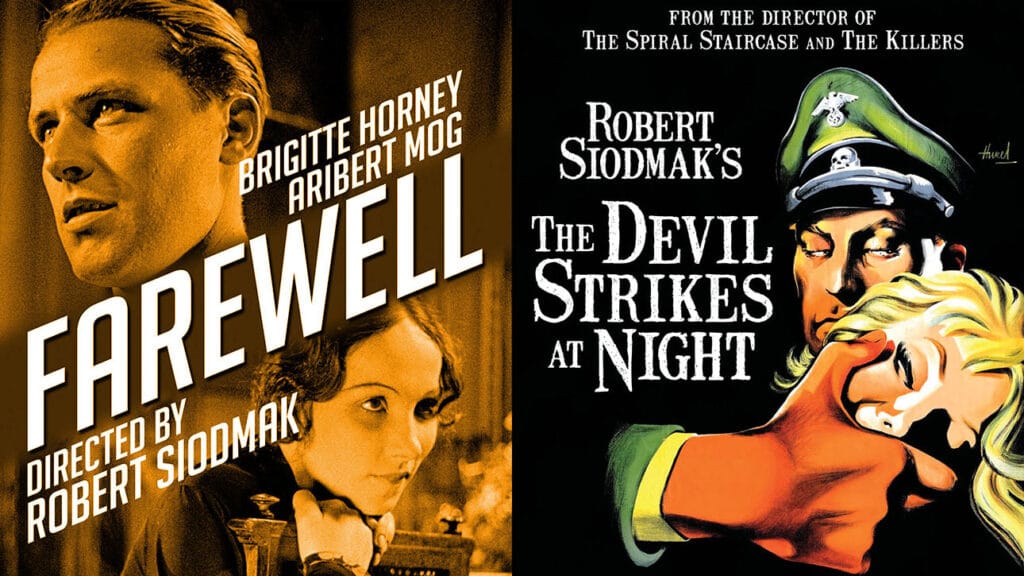

Farewell (Abschied, 1930)

This very early German talkie boasts an adroit, even impudent command of the new sound medium along with an assured visual style that marries realism with flashes of visual poetry. Among its groundbreaking devices is the use of a theme song performed during the credits.

That song is written and performed by Erwin Bootz, most famous as a member of the scintillating vocal group, the Comedian Harmonists, who were taking Europe by storm. In Farewell, he plays a character called Bootz, essentially himself, a blond pianist who spends almost the whole film in his room playing the film’s piano score. That’s the next groundbreaking element: an ironic diegetic piano that can be heard through much of the action, accidentally rendering everyone as characters in a play who are almost singing their lines.

The entire film takes place on the floor of a dingy, claustrophobic rooming house where various types live in each other’s pockets and everybody hears everybody’s business as well as the piano. To keep it cinematic, the film constantly cuts between rooms and dialogues, finding visually interesting ways to convey the cramped atmosphere.

Like the characters, the audience is continually aware of off-screen space, thanks to many sound cues like the doorbell, the piano, shouts and exclamations, and a major player in the drama, the vacuum cleaner. This machine signifies a German obsession with cleanliness. The house-proud hausfrau is a cultural type; I remember my German aunt saying such characters on TV commercials are referred to as “Mrs. Saubermann”, and it’s interesting that they use an English title. The irony is that this obsession with cleanliness requires a concomitant amount of constantly generated dirt.

One of the boarders is Neumann (Frank Günther), a cabaret host who rehearses his patter in his room. Thus the era’s cabaret culture is present by proxy, and perhaps some of the skimpily dressed women also work in that environment. Or perhaps they’re something else entirely.

A decadent, tawdry, tatty vibe of degenerating respectability is presided over by the hideous landlady, Frau Weber (Emilia Unda), a gossip and pot-stirrer who’s just as capable of encouraging bad behavior as denouncing it in the next breath. Unda’s most famous role was the stern, tyrannical headmistress in Leontine Sagan’s Mädchen in Uniform (1931). That moving, pioneering lesbian drama is also recently available from Kino Lorber and is highly recommended.

Farewell is surprisingly frank about the idea that people quietly have sex in their rooms. One major scene of pillow talk, again using off-screen space, is conducted while we watch the smoke rising from a cigarette in the ashtray on a table. In his commentary, historian Anthony Slide quotes the director’s brother, Curt Siodmak, who stated that this idea was a last-minute replacement for ruined footage. The history of cinema is filled with brilliant improvisations after mistakes and disasters.

The main characters are two lovers who might not be made for each other but perhaps deserve each other. Peter Winkler (Aribert Mog), who arrives to show off some beefcake in a bath scene, hasn’t told his girlfriend Hella (Brigitte Horney) that he’s leaving Berlin tomorrow for a good job in Dresden. Their mutual play of baited jealousies amid lovey-dovey business hardly bodes well and leaves them susceptible to the almost malevolent cross-purposes of other tenants. If Siodmak’s debut in this same year was the privately made romp People on Sunday (Menschen am Sonntag, 1930), this first talkie could have been called People Are Satan.

Three other members of the menagerie are the loud, simpering servant Lina (Martha Ziegler), whose wails over the exploding vacuum cleaner introduce us to the drama proper and its obsession with off-screen space; Bogdanoff (Konstantin Mic), a Russian wheeler-dealer with lots of ready cash; and the sponging, snooping, filching Baron, who will surprise us. He is played by Vladimir Sokoloff a few years before arriving in Hollywood for an illustrious character career.

Siodmak isn’t the only celebrated artist behind the camera. The photographer is the pioneering Eugen Schüfftan, who would win an Oscar for The Hustler (Robert Rossen, 1961). The writers are Emeric Pressburger and Irma von Cube. Pressburger, Jewish like Siodmak, was forced to leave the German industry and would become one of the great creatives in British cinema. Von Cube came to Hollywood and received an Oscar nod for Johnny Belinda (Jean Negulesco, 1948).

Farewell was popular enough that its studio, UFA, decided to reissue it the next year with a tacked-on “happy ending” without the participation of Siodmak or the main stars. It’s included in this restored print as a kind of postscript.

The Devil Strikes at Night (Nachts wenn der Teufal kam, 1957)

Nominated for an Oscar for Best Foreign Film, this police procedural about the search for a serial killer derives its uncanny complexity and suspense from its morally compromised setting: Berlin in the “war-summer” of 1944. As the city is being bombed every night, everyone makes cynical ironic remarks about how well the war’s going. Morale and morality seem at equally low ebb while the bloom wears off of Hitler’s promises and everyone tries to survive the grind.

After an eerie, nightmarish credits sequence of a hunted man buried in mud, the opening scene feels crudely satirical as a local Nazi bureaucrat, Willi Keun (Werner Peters), offers praise and prizes to a group of young women in shorts and tight blouses. He gets handsy but comes across as no more dangerous than the Germans in the later TV series Hogan’s Heroes before he goes to have fun with his mistress, a hard-bitten waitress named Lucy (Monika John).

Gobbling potatoes at her inn is Bruno (Mario Adorf), a local delivery man of great strength. We later learn he’s got a long record of petty crime with local police and he’s officially classified as insane, and that’s after we realize he’s a murderer. Hiding in the expressionist shadows under the stairs, he emerges to strangle Lucy for her purse while Keun is sleeping in her room. She cannot scream because one hand is over her mouth, but the air raid siren screams for her in another startling use of sound from Siodmak.

As naturally as night follows day, Keun is slapped in the pokey awaiting trial, for the winning combination of incompetence and expedience seems to define the culture – except for homicide commissioner Axel Kersten (Claus Holm), fresh from the Russian front with a limp. He notices that Keun lacks a thumb, which should make it awkward to match the marks on Lucy’s corpse, if anybody bothers. More disturbingly, Kersten realizes that the case is similar to other incidents of recent years.

Kersten’s boss observes the irony of being concerned with isolated murders, as reported sensationally in the press when thousands die daily and official propaganda never mentions bombs on Berlin. One notion here is that this toxic environment is a perfect cover for a killer to run loose, or that his activities are just a personal version of the larger status quo. It gets worse as Kersten’s investigations cross paths with conflicting official agendas. Justice may literally be impossible in this world, or at least irrelevant, when there’s no place for smart or moral people and when the powers that be live by murder.

The suspense over whether Kersten will get his man has a particularly queasy quality, especially in the scene where Bruno meets a Jewish woman (Margaret Jahnen) who really doesn’t need to be making friends with him. It means nothing to Bruno when she says her husband died somewhere in Poland he’s never heard of a place called Auschwitz, and in this, his backward mentality reflects most of his fellow Berliners.

Another chilling scene is Bruno’s recreation of a murder in a forest. As Siegfried Franz’s score adopts modernist dissonant gestures, the camera goes on a free-running journey halfway between Bruno’s subjectivity and investigative reality.

Another profoundly disturbing aspect of The Devil Strikes at Night is that, though we may wish to console ourselves that it’s set in an extreme context in the past, its observations on the corrupt and corrupting nature of power, and how multiple forces cross to obscure truth and justice, aren’t irrelevant anywhere today. If they were pertinent only to a safely removed history, there would have been no need to make the film or watch it.

Siodmak produces as well as directs, so he’s fully in charge of his material. It was easy for him to shoot the film amid some wartime ruins since they were still around. Cinematographer Georg Krause shot it the same year he did Stanley Kubrick’s Paths of Glory, quite a year for him.

Werner Jörg Lüddecke’s screenplay for The Devil Strikes at Night, based on an article by Will Berthold, is inspired by the real case of serial killer Bruno Lüdke, although the film makes no pretense of being a documentary. One may compare this film instructively with Fritz Lang’s M (1931), also inspired by a real case, in which the underworld sets up its own alternative justice system to ward off the heat.

Film historian Imogen Sara Smith places Siodmak’s film within three contexts: Siodmak’s career and themes, postwar German cinema in general, and wider cultural history. For example, she observes that recent scholarship on Lüdke tends to believe he was an innocent scapegoat, which lends yet another chilling dimension within which to absorb this bitter analysis of official power and how people willingly collaborate with it. Even in this film, which clearly depicts him as a killer, Bruno is happy to help the authorities with what he knows. The layers of bitter irony multiply as in a house of mirrors.

The long unavailability of Farewell and The Devil Strikes at Night in Region 1 could have led us to assume these are minor Siodmaks. If so, we need the rest of his minor output.