In Héctor Babenco’s 1991 screen adaptation of Peter Matthiessen’s novel, At Play in the Fields of the Lord, two American explorers find themselves stranded deep within Brazil’s Amazon basin after their plane runs out of fuel. Played by Tom Berenger and Tom Waits, the two characters agree to turn mercenary and bomb a nearby native village inhabited by the Niaruna tribe in exchange for the fuel they need to continue their journey. But after a change of heart, Berenger’s character — himself part Native American — ingests a hallucinogenic substance, gets in the plane on his own, and parachutes into the Niaruna village as the unpiloted aircraft crashes.

The story builds to an inevitable collision between the Niarunas, a group of American Christian missionaries, and the local police commander who’d arranged for the bombing on behalf of gold miners moving into the area. Fittingly, the film’s parachute scene would provide the initial seed of inspiration for Roots, the sixth album by the Brazilian thrash/death metal act Sepultura, and inarguably one of the most radical departures from convention in heavy metal history. As then-frontman Max Cavalera recalls in his 2014 autobiography, My Bloody Roots, he was watching the film while sipping wine on his couch one night in 1995, shortly before the band was to commence pre-production on its follow-up to 1993’s Chaos A.D.

Though traces of a Latin approach to rhythm appear as far back as Sepultura’s ultra-crude debut EP, 1985’s Bestial Devastation, the band members identified so passionately with metal that, much like teenaged metalheads everywhere else, they rejected the music they’d heard growing up and focused instead on emulating their European and American thrash / black / death metal idols like Slayer, Kreator, Hellhammer / Celtic Frost, Venom, etc. If you listen closely to the first four Sepultura albums — Morbid Visions (1986), Schizophrenia (1987), Beneath the Remains (1989), and Arise (1991) — it’s clear that the band was making its best effort to play in a “straight” thrash or death metal style. (The word sepultura is, in fact, Portuguese for “grave”.)

But you can also hear a faint twist of something else. Even at breakneck tempos, the space between the downbeats creates a sway in the thrash groove that most likeminded bands from elsewhere just didn’t possess as part of their musical vocabulary. With Chaos A.D., the underlying Latin American rhythmic sensibility came to the forefront as the defining component of Sepultura’s sound. As author Jason Korolenko discusses in his Sepultura biography Relentless, also from 2014, the band’s relocation to the States in 1992 amplified its collective awareness of the Brazilian textures that had been seeping into its music all along.

Chaos A.D. also foreshadowed what was to come with “Kaiowas”, an acoustic instrumental named after and dedicated to the Kaiowa branch of the Guarani, a people who have repeatedly engaged in orchestrated mass suicide in response to forced displacement in Brazil’s state of Mato Grosso du Sul. But in spite of its thematic inspiration, acoustic structure, and rolling beat that falls somewhere between Braveheart and Bahia, “Kaiowas” in no way prepares listeners for the chaotic splattering of musical elements that takes place on Roots. If Chaos A.D. marks the point where, musically speaking, Sepultura embraced their Brazilian identity, on Roots, the band dive headfirst into sonic terrain as unfamiliar and exotic to its own members — and, indeed, to most Brazilian listeners — as it would end up sounding to the sizeable international audience the album reached upon its release.

In fact, as Cavelera admits in his book, he and his bandmates were only marginally aware of Brazil’s indigenous population. Through Angela Pappiani, at the time the communications coordinator for Brazil’s Núcleo de Cultura Indígena (Indigenous Culture Center), he was stunned to discover that Brazil is home to hundreds of native tribes, each with their own culture and dialect and each facing threats of land loss and habitat destruction at the hands of aggressive governmental land-acquisition policies, industrial practices, and encroaching rancher settlements.

Watching Berenger plunge into the Niarunas’ endangered world sparked in Cavalera an urge to do the same, both literally and creatively. In his book, Cavalera talks about his desire to work with tribes who harbored hostility towards — and even tended to kill — outsiders, but Pappiani suggested the Xavante people instead. Unbeknownst to the band, the Xavante (pronounced sha-VAHN-tee) were already known to a broader “world music” audience, thanks to an album of their traditional songs, 1994’s Etenhiritipá — Cantos da tradição Xavante, which had also been spearheaded by Pappiani (and distributed by Warner Bros).

Additionally, as University of Iowa anthropology professor Laura R. Graham explains by phone, the Xavante had long ago become a loaded symbol for Brazilians who were old enough to remember.

“In the ’50s and ’60s — even the ’70s,” says Graham, “the Xavante were the most famous Indian group in Brazil. That has to do with the government of [longtime president] Getúlio Vargas, who was opening up the interior of Brazil to capitalist expansion. It was all part of his plan to conquer what he called the ‘hinterland’ and bring it under the control of the national society. It just so happened that that frontier expansion involved laying down a telegraph line across the country, opening up into the Amazon area and, basically, ‘conquering’ or ‘pacifying’ indigenous peoples — what the government called ‘contacting’ them — bringing them into the domain of the national society. The government chose to focus national media attention on the Xavante ‘contact’. They actually embedded journalists into what they called the ‘pacification team’. During the late ’40s, they had these embedded journalists who wrote regular communiqués that were being published in the national newspapers.”

Graham continues: “Those journalists’ reports portrayed the Xavante as these savage, violent Indians. When the Xavante finally entered into peaceful relationship by exchanging arrows for metal goods the ‘pacification team’ had left in strategic places — basically when the Xavante were surrounded and made the decision to ‘succumb’ (the government’s view of their cooperation, not theirs) — it was portrayed in the national media as a huge victory. This was a huge symbolic campaign that represented the conquest of the national society over the interior and its inhabitants. The generation of people who grew up in the ’70s and ’80s — Sepultura’s generation — wouldn’t necessarily know that, but if you talk to people in their parents’ generation, the Xavante were this household name that everybody knew. It was like ‘they’re savages who live in the interior.'” (In her 2005 academic paper, “Image and instrumentality in a Xavante politics of existential recognition: The public outreach work of Eténhiritipa Pimentel”, Graham also points out that “Mario Juruna, the first indigenous person to be active in national politics, was Xavante.”)

It didn’t require such extensive knowledge of history for Cavalera and his then-bandmates — his younger brother Igor Cavalera on drums, lead guitarist Andreas Kisser, and bassist Paulo Pinto, Jr. — to understand that they were making an overture to a marginalized community. With that in mind, in 1995 Sepultura set off for the interior, a foreign land within their own country. On a trip organized by Pappiani, the band — along with a small party of people that included producer Ross Robinson, a photography team, and Pappiani herself — boarded four Cessna prop planes, recording gear in tow, and made what Cavalera and Korolenko’s books both describe as a hair-raising journey to Pimentel Barbosa, the Xavantes’ reservation home, known to them as Eténhiritipa (also written Etenhiritipá, Etenhíritipa, Etéñitipa), and located on a patch of cerrado (tropical savanna) in the western part of Brazil.

The plane, writes Cavalera, “looked like a Volkswagon inside. You could literally open the door from inside and jump out if you wanted. It was really scary. It looked so shaky and old.” Nevertheless, the band’s excitement comes across in both books, as well as in video footage shot by a Portuguese crew that has since surfaced on YouTube. Received as honored guests, the band stayed at Pimentel Barbosa for several days, in the process recording a set of musical sequences that would end up providing a running thread on Roots.

Several questions jump out here: How much did the Xavante grasp what they were getting into? Did they have sufficient cultural background to “understand” metal? Did they even like Sepultura’s music? What would they think of the final product? Would it sound like ugly noise to them? For all the benign intentions motivating Sepultura and Pappiani, was the band in danger of carelessly or inadvertently exploiting this community? Was this another example of “civilized” society acting paternalistically towards a pre-modern culture and playing into “noble savage” stereotypes? London-based sociologist Keith Kahn-Harris — author of numerous books, newspaper columns, and academic essays that explore heavy metal, Jewish identity, and other sociological themes — explicitly addresses these concerns in a 2000 article he wrote on the album, titled “Roots”?: The relationship between the global and the local within the Extreme Metal scene”, for Cambridge University’s academic journal Popular Music.

In the article, Kahn-Harris (who, incidentally, authors a blog under the nickname Metal Jew), writes:

Whilst the Xavante appear to have been treated with respect and receive royalties, it is unclear how they understood the project and what they will get out of it. The Xavante had little say on how the piece was set within the album (although ‘Itsári’ [see below — Ed.] was not overdubbed at all). Neither can Sepultura ensure that those who purchase their albums will not exoticise the Brazilianness in the project. Nonetheless, Sepultura did approach Roots in a spirit of discovery that avoids many of the pitfalls that other artists have fallen into in such projects. The collaboration was not intended simply to add exotic ‘colour’ to their music, but was a sincere (if perhaps naive) attempt to collaborate and learn from Sepultura’s fellow Brazilians. Moreover [as Graham points out in several scholarly publications — Ed.], the Xavante of Pimentel Barbosa have become skilled at dealing with non-Xavante Brazilians and non-Brazilians (Graham 1995) and Cipasse, the president of the Xavante of Pimentel Barbosa and Sepultura’s primary contact, had toured with Milton Nascimiento. The Xavante also released a statement warmly commending the collaboration.

Graham, whose work has focused on the Xavante and Wayuu people for decades — specifically with respect to, as she explains it, “the politics of representation and the power dynamics that are loaded into that representation” — is quick to point out that the Xavante have always acted as enthusiastic agents of — as we say in modern pop-culture parlance — getting their music out there. In point of fact, both parties were making what we can view as “benevolent” gestures, and both were “using”, if you will, each other’s music as vehicles for their own aims, which in both cases entailed a profound sense of responsibility when it comes to music.

“The Xavante,” says Graham, “are very interested in having the world know about them. For them, music functions as a medium for entering into other realms — whether they be other dimensions of existence or other cultures. In Xavante culture, it’s the men who interact with these foreign domains. Well before they had any contact with white people, part of their culture has always entailed that men engage the spirit world, especially through music. This happens in their dreams. Having visions with the spirit world or the world of people who have died, for them that happens via dreams, and it’s a male domain. One of the primary vehicles of that interaction is music. Not all, but most of their music is inspired — you could say ‘composed’, although they say received — in their dreams through encounters with other worlds.”

“When people come and visit the community from the outside,” she continues, “one of the things the Xavante ask them to do is sing them a song. Music is this medium for entering into relations with others — others meaning spiritual beings or, for example, white society or other cultures. The Xavante want to be known and they want their culture to be known. They want their music to be known because they think it’s beautiful and view it as a contribution to humanity. It’s like, ‘We have something beautiful to contribute to humanity — and, by the way, here we are suffering. We want people to know who we are and that we exist.’ And so when they got this proposal from a musical group that wanted to come jam and share music with them, they loved it.”

Of course, it was a risky move for both parties. Roadrunner Records, the band’s label at the time, initially expressed trepidation — quite understandable, considering there was no precedent for how such an unorthodox fusion would be received by the band’s metalhead fanbase. From the Xavante perspective, they were placing a lot of trust in the hands of people who might not accurately represent them. As Graham points out, “they didn’t have control over what the band did with their sounds, but they did stipulate that Sepultura could not manipulate their sound. They didn’t want it to be synthesized or distorted. It was like, ‘You can play around it, but you can’t change how it sounds.'” Max Cavalera remembers in his book that Xavante leader Cipasse made his terms explicitly clear, while Pinto, Jr. explained in a February 1996 interview for MTV Europe that Cipasse was very thorough in requesting that the band provide him with a detailed accounting of what they intended to do with the music. “They won’t let anyone touch [i.e., deface] their culture,” said Pinto, Jr. “That’s the good thing about them. They’re very [mindful] of their culture.”

Friction Between the Indigenous and the Modern

In the same MTV clip, Igor Cavalera offered the following: “The main thing that we got from that [experience] is, a lot of people talk about saving the tribes. But they don’t need to be saved. They live a lot better than any of us, I think. They have no stress with money or anything like that. If they’re hungry, they go hunting. They have the river, they drink the water. Balance is the main thing that they have. For us, it was amazing for us to see that people still live like that today, totally in control of their lives without worrying about stuff that’s [ultimately] worthless.”

That said, while Graham does describe the end product as successful in terms of the Xavantes’ desires for it, she also adds a caveat: “In one sense, the collaboration with Sepultura achieved something that was important to them, which was this musical interaction and this broader dissemination of their culture. The larger scope is that people get exposed to it, but there’s no context for understanding what’s going on with these people. That would be my critique — that although the Xavante are happy to be known, when you put this interaction in a broader context, Sepultura didn’t do more than just disseminate it. They didn’t provide any context for it.”

Maybe so, but the music on Roots, as well as its accompanying imagery, signals on many levels the band’s intentions to present the Xavante in a dignified light. In pure musical terms, part of what makes the album so compelling — regardless of how you feel about the music itself — is how it captures an anomalous convergence of two musical paths that would likely have never intersected on their own.

Not to mention that no one could have anticipated just how many people this music would reach or how far it would end up traveling. Released in Europe on 20 February 1996 and then on 12 March (three weeks later) in the States, Roots introduced new colors to the metal palette on an unprecedented scale. In so many ways, no other metal release has come close — a shock given that the genre has since worked its way onto every inhabited continent on the globe. Nowadays, in spite of omnipresent high-speed digital connectivity, we can still only point to a handful of acts that have even nibbled at cross-continental mass appeal by blending metal with music that strikes Western ears as comparably remote and alien.

Two recent examples stand out: Melechesh, who originally hail from Jerusalem’s West Bank and draw from their Armenian/Assyrian heritage as well as ancient Sumerian cosmology, and Taiwan’s Cthonic, who similarly center their aesthetic around classical Taiwanese mythology. (Numerous contemporary Scandinavian artists fuse metal with Nordic folk music as well.) Nevertheless, although metal continues to gain traction throughout the Middle East, Asia, Latin America, Africa, and elsewhere, Melechesh and Cthonic represent the exception rather than the rule. Not to mention that their popularity hasn’t made them nearly as visible as Sepultura was in 1996.

It would be grossly reductive to view Brazilian music through the lens of the country’s most widely recognized artists. But the fact remains that, to this day, only a handful have achieved household-name status outside of Brazil. A short list of familiar names comes to mind: João and Astrud Gilberto, Antonio Carlos Jobim, Caetano Veloso, Os Mutantes, and Gilberto Gil. Straight out of left field, Sepultura somehow edged their way onto that list somewhere between 1989 and 1991. Just a few years earlier, when the members of Sepultura first engaged in the then-popular activity of tape trading with other metalheads in Europe and the States, Brazil as a music market was effectively regarded as a third-world backwater, while envelope-pushing forms of metal hadn’t yet clawed their way out of fringe/underground-level appeal.

Several of the aficionados with whom the Cavalera brothers and their peer group corresponded and traded demos by mail would go on to play pivotal roles in bands, publications, and record labels. Sepultura’s career trajectory would also align perfectly with the surging international popularity of thrash, death metal, and grindcore. Still, Sepultura achieved rarefied status as one of Brazil’s most celebrated musical exports more or less against all odds. Looking back, the band’s ascent unfolds like a fairy tale that, in some ways, culminates with Roots. One of Roadrunner Records’ bestselling titles ever, Roots has sold 500,000 copies in the States (officially certified gold by the RIAA in 2004) and made a commensurate splash, relatively speaking, in other markets throughout the world.

Prominent slots on European summer festival dates in the summer of 1996 bookended by two separate American outings supporting Ozzy Osbourne — including a run as a middle-billed first-stage act on the inaugural Ozzfest in autumn of that year — reflect Sepultura’s stature at the time. Accordingly, international media hype swelled throughout the year, with print and television outlets engaging in enthusiastic coverage both leading up to and following the album’s release. Remnants of that coverage survive online, including a charmingly dated YouTube clip of a Belgian TV segment that shows Bjork and Dave Grohl enthusing about Sepultura backstage at a Belgian festival date. MTV Europe, meanwhile, covered the band’s European headlining club jaunts in February and November-December with weeks’ worth of Roots-themed Headbanger’s Ball specials filled with interviews and live footage.

To find an analogous contemporary phenomenon requires looking outside of metal and pointing instead to South Africa’s satirist hip-hop duo, Die Antwoord. Both Die Antwoord and Sepultura carved out a new place for their respective countries on the worldwide pop-culture map with unflinching glimpses into street-level conditions that in all likelihood didn’t thrill either nation’s tourism board. Both groups have managed to pose incisive, even essential questions about their homelands while still reveling in a blunt, unrefined lyrical attack. Paradoxically, by using guttural, obscenity-laced vernacular, each act raised the profile of its native country. Moreover, Sepultura and Die Antwoord both openly challenged their governments’ histories of violence and oppression and, as such, made audiences wonder what each nation’s position in the world might look like going forward.

Roots touches briefly on the military dictatorship that had loosened its grip on Brazilian life just a decade prior to its making, as the members of Sepultura hit their teens. Korolenko’s biography thoroughly illustrates the band’s origins within a social framework where disappearance, imprisonment, exile, and general climate of fear and injustice had been standard operating procedure dating back to the late 19th century. Although the band members themselves were only partially aware of these conditions, they would come to play a huge role in shaping their music. (As Max Cavalera writes in his book, because his father worked in the Italian consulate, the Cavalera brothers had mostly been shielded by their father’s status. That all changed when their father passed away.) However, the band had written about the harsh realities of life under despotic regimes on its previous four albums.

This time around, after several rounds of touring abroad, when Sepultura focused its collective gaze on Brazil, it did so with a vastly expanded worldview. On Roots, shades of the friction between modern and indigenous Brazil, with ecocide and cultural extinction as inevitable byproducts, float in a messy metallic soup that emanates a self-conscious awareness of Brazil’s colonial and post-colonial history. Aside from the obvious Xavante presence, at various points the album’s lyrics take the listener into the severely impoverished favelah shantytowns, revisit the 1988 killing of environmentalist Chico Mendes, and name-drop abolitionist Zumbi, a modern-day folk hero who, in 1675, assumed leadership of the refugee-slave settlement Quilombo dos Palmares and held out for two decades in heroic resistance against steady armed invasions by Portuguese colonists.

The album opens, appropriately enough, with a brief introduction of insect sounds recorded at Pimentel Barbosa before launching into “Roots Bloody Roots”, a song that, lyrically speaking, works as a declaration of identity and resilience from the point of view of the Xavante (or others who face similar circumstances) but also works as a self-empowerment anthem for heavy metal’s trans-national community as well. In the aforementioned 1996 MTV Europe clip, Max Cavalera explained the meaning behind the song as: “Don’t give in. What you believe is for life, even if people try all the time to change you. The song is about ‘don’t let the bastards grind you down.'” Cavalera also hints at the Xavantes’ predicament when he sings the lines “pray / we don’t need to change our ways to be saved” and “rain / bring me the strength / to get through another day / all I wanna see / set us free,” along with affirmations like “I / believe in our fate / we don’t need to fake” and “I say / we’re growing every day / getting stronger in every way”.

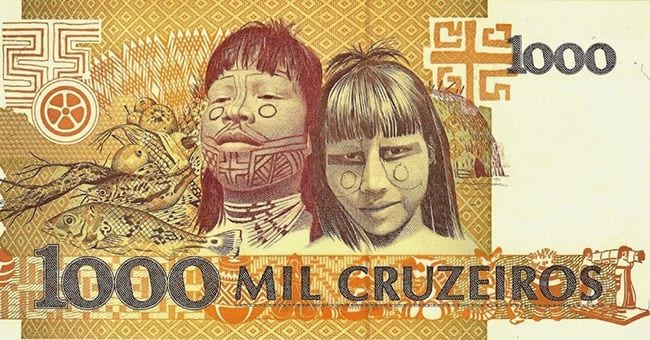

The Cavaleras, Kisser, and Paulo Jr. didn’t pull all of these themes together into any kind of coherent, explicitly articulated picture, but they didn’t have to. The various references that permeate the songs give the album an aura that evokes powerful sensations, whether you understand the references or not. Much like the music, Thomas Mignone’s video for “Roots Bloody Roots” throws several disparate elements into the same pot, including the appearance of indigenous natives, Brazilian percussionist Carlinhos Brown’s group Timbalada, and the Brazilian martial art of capoeira, a once-clandestine self-defense technique invented by slaves who, out of self-preservation, disguised their moves as dance so as not to incur the violent wrath of their white slavemasters. Several shots feature Max Cavalera screaming in catacombs under the city of Salvador where slaves were once bought, sold, and killed. Even the album’s cover art, with its depiction of an indigenous tribesperson adapted from the design of Brazil’s (now-discontinued) 1000 cruzeiro real dollar bill, announces a journey into uncharted musical waters.

To say the least, Roots is also loaded with rhythms and instrumentation that had never appeared in a metal setting before — or certainly not to such a degree. Right from the outset, Igor Cavalera’s high-pitched ra-ta-tata rototom fills that preface the first verse on “Roots Bloody Roots” resound with a distinctly Latin timbre. On the next track, the berimbau, a Brazilian stringed instrument whose sound resembles a jaw harp, introduces “Attitude”, a tune marked by its distinct fusion of a hip-swaying Afro-Latin groove with sulfuric metal crunch. Other Afro-Latin instruments such as the timbau, lataria, and xequere clatter and clang throughout the album, giving a bead curtain-like fabric to the din.

Trouble on the Road Ahead

Indeed, several of the songs — “Breed Apart”, “Endangered Species”, “Ambush”, etc. — take surprise hairpin detours into extended ensemble percussion sections that sound totally incongruous yet somehow still find their place within thick layers of distorted guitar abrasion, screams, and pounding drums. And, of course, in a kind of Amazonian answer to Alan Lomax, Roots prominently features the field recordings that the band and producer Ross Robinson made at Pimentel Barbosa.

Both Max Cavalera and Korolenko’s books detail various aspects of the album’s recording process, including how Robinson, in order to operate the recording gear at Pimentel Barbosa, had to use power generators that ran out just as he had captured a performance of “Itsári” (“Roots”), the album’s centerpiece collaboration between the band and Xavante tribesmen that highlights a Xavante healing chant, “Datsi Wawere”, over an acoustic-guitar / hand percussion arrangement reminiscent of “Kaiowas”. Elsewhere, in an almost psychedelic twist, another Xavante chant suddenly bubbles up after the eruptive climax of “Born Stubborn”, as residual guitar feedback glows like angry lava in the aftermath of repeated double bassdrum volleys.

The end of the song sounds like the band played two completely unrelated reels of analog tape at the same time and decided to mash them together. When a volley of drum hits slam into the picture out of nowhere as the Xavante continue to chant, a series of shrieks from Max sounds like screeching tires as the noise part of the song swerves off the road and the drums provide the tumultuous crash, Kisser’s guitar trilling insistently the way wheels would spin and smoke would rise from a heap of twisted metal. The combined effect is one of giddy chaos that conjures imaginery scenes of the band cheering and high-fiving around the mixing console as they listened back to the strangely elegant musical train wreck they’d just created.

Finally, in what is perhaps the album’s most audacious creative decision of all, Roots concludes with 13-plus minutes of the insect sounds that open the album, blended with ambient sounds recorded with Carlinhos Brown in the canyon outside of Indigo Ranch Studios in Malibu, California (at the time Robinson’s studio of choice). Brown also arranged and guided the bulk of the percussion performances throughout the album, and he even delivers, of all things, a scat-style lead vocal rap on “Rattamahatta”, a call-and-response he wrote that turns a favelah into the scene of a rousing block party-like celebration.

“Rattamahatta” may or may not be named after a rat from Manhattan — Max Cavalera writes in his book that he still isn’t entirely sure what Brown was singing about, but that just goes to show how free and open to outside input the band’s approach was during this period. “Rattamahatta” also features a guest appearance by then-Korn drummer David Silveria, while Mike Patton, DJ Lethal, and Korn vocalist Jonathan Davis all appear on the gloomy, ambient “Lookaway”, a song that, in spite of its turntable scratching and musicians, sounds nothing quite like rap, nothing quite like metal, and nothing quite like anything in between, either. Given Robinson’s presence and his massive success two years earlier as the producer of Korn’s game-changing self-titled debut, it’s no surprise that a nu-metal streak runs through Roots, as well. But the album’s barbed mélange of musical styles, with its wealth of lively, noisy ingredients, easily separates its content the stereotypical nu-metal output of the era.

For all the vitality and daring of this music, however, with hindsight we can now see that, as much as Sepultura was leaping over boundaries at this time, the band was also straining against some creative limitations. Max Cavalera’s caustic and increasingly one-dimensional brand of rage, not to mention his transition to a more simplistic and brutish riffing style, clashes somewhat with the technical sophistication that Kisser, Igor Cavalera, and Paulo, Jr. were pushing towards. To be fair, in the Brazil of the Cavalera brothers’ teens, the simple act of having long hair and wearing a heavy metal t-shirt could very likely get you killed by police. At the time, Brazilian police forces basically exercised free rein in killing people indiscriminately, according to both biographies as well as various interviews that band members have given over the years.

Case in point: not long after Max Cavelera’s American replacement Derrick Green relocated to Brazil in the year 2000, he had an encounter with police in the restroom of a bar where they held a gun to his head. When they realized who he was, they insisted on trying to buy him drinks. For the other members of Sepultura, the constant specter of police brutality was a fact of life. In his book, Max Cavalera describes how, although he had no qualms about getting into fistfights or brawls, the police utterly terrified him. And, for reasons the band has elucidated over the years, ending up in a São Paulo prison might as well have been a death sentence. So the bile that engulfs Roots — with its almost overbearing sense of adolescent-level persecution and self-pity in lines like “criticize and call me negative / you’ve never faced life or reality / motherfucker you don’t undersand / pain and hate” — does have a genuine basis. But looking back, its fair to wonder how much further the band could have gone with Max.

As it turns out, tensions between Cavalera and his bandmates had been simmering in the backdrop for years by the time Sepultura recorded Roots. Those tensions continued to mount over the course of 1996, even as the groundswell response to the album catapulted Sepultura to its all-time peak level of success. Things came to head in a now well-documented sequence of events that culminated in Kisser, Igor Cavalera, and Pinto, Jr. severing their ties with Gloria Cavalera — at the time the band’s manager and also Max’s wife — on 16 December 1996, after a performance at London’s Brixton Academy that would end up being the classic Sepultura lineup’s final show together. (A warts-and-all recording of that show eventually saw the light of day in 2002 as the live album Under a Pale Grey Sky, at the beginning of which Max Cavalera greets the crowd by shouting “greetings from the third world.”)

As many sources have reported since then, Max’s bandmates felt that his wife was too focused on his interests instead of the band’s collective good, and they resented that she and Max had cultivated an image that downplayed their creative contributions. (Gloria Cavalera’s blog posting of Max’s “Roots Bloody Roots” demo, with her insinuation that Max deserves all the credit for the song, betrays a lack of understanding of how basic band dynamics and group collaboration work.)

Still reeling from the death of Gloria Cavalera’s son Dana Wells, which had occurred four months earlier, naturally the couple felt stung and betrayed by the other band members’ seemingly ruthless timing. (Max has repeatedly cited the pressures of success and maintaining a rigorous touring schedule as additional contributing factors.) Afterwards, in what must surely rank somewhere in the top five of music’s all-time brotherly feuds, Igor remained with Sepultura for almost another decade, played on four more albums, and didn’t speak to Max the entire time. Immediately following the 1996 split, Igor was adamant in his decision to stay, saying some rather pointed things on record about his brother. Both sides traded jabs in the press for years, but in 2006, Igor ended up leaving the band as well, under what initially looked to be less acrimonious circumstances. (Though details remain somewhat murky, his diminished enthusiasm for metal and his divorce from his wife Monika — who had, in an ironic twist, by then been instated as Sepultura’s manager — presumably weighed in his decision.) But after reconciling with his brother and forming the Cavalera Conspiracy with him shortly after his departure, these days Igor now appears to be as estranged from his former bandmates as he once was from Max.

Although no one involved has ever suggested musical disagreements as source of friction with Max, the creative and thematic freedom of Sepultura’s post-Max output (while Igor was still onboard) raises questions about what would have come next had Max had remained at the helm. Would lightning have struck twice? More precisely, would trying to recapture any of the essence of Roots come off as contrived? Sepultura has, almost from the very beginning, defined itself as an act that refuses to make the same album twice. To this day, just about every release in the Sepultura catalog stands apart from the rest, and any given title stands in stark contrast to whatever the band put out immediately before or after.

By comparison, Max has essentially built a second career on repetition (not to mention grief) with his solo vehicle, Soulfly. In an interview with the Dutch YouTube channel Face Culture from March 2016, Max referred to Roots as “the blueprint for the rest of my career” in terms of his taste for incorporating musical styles and instrumentation from all over the world. Where he once, as a member of Sepultura, pushed himself to expand the metal lexicon, he has arguably regressed in his approach to writing riffs since leaving. Sure, Soulfly has a knack for anthemic, fist-pumping grooves, but it can’t be a coincidence that Max ceased challenging himself as a musician when his creative partnership with Andreas Kisser dissolved. Likewise, while Sepultura’s choice of subject matter has fanned-out in myriad directions, Max for the most part continues to wallow in unexamined, even solipsistic anger — a surprise considering the thoughtfulness and depth he tends to show in interviews.

In any case, the band’s star was clearly trending upwards as the interpersonal wedge grew deeper and deeper. Max’s book, in fact, opens with: “On December 16, 1996 my band Sepultura was on fire. We were one of the biggest heavy metal bands on the planet.” But that success was prematurely cut short just as Sepultura was poised for what would undoubtedly have turned out to be a triumphant victory lap headlining the US and other parts of the world well into 1997.

When the newly-retooled Sepultura came roaring back in late 1998 with new frontman Derrick Green on the Roots follow-up, Against, the band’s strident sense of rejuvenation and creative ambition burned through in the new music. But those qualities wouldn’t be enough to prevent the hemorrhaging of fan loyalty. In the US, Against sold one-fifth as well as Roots, thus ushering-in a steady decline in Sepultura’s American following. Though the band retains superstar status in Brazil and continues to tap into out-of-the-way markets like Siberia, India, China, Morocco, Dubai, South Africa, Cuba, and South America — often to huge crowds — barring a miracle comeback Roots will forever be remembered, fairly or not, as a career peak. Not to mention that the absence of Igor Cavalera casts doubt on the band’s continued use of the name — a decision Igor at first supported but has since derided.

As much a document of a group reaching the end of the line as it is a snapshot of that group setting its sights as far out to the horizon as its members dared to reach, Roots percolates with unresolved questions. Perhaps the most tantalizing: With the enormous imprint that this album left on metal, when will someone finally step up, follow Sepultura’s lead, and push the genre another step further by cross-pollinating it with sounds most of us have never heard? Rest assured, that’s already happening. But how many stars would have to align for someone, first, to pull it off without resorting to clichés — without, basically, sounding like they’re just imitating Roots — and, second, to do so in a way that catches the public’s attention on a global scale.

Whatever your opinion of the music on Roots, you can’t deny the artistic bravery that went into its making. We might be waiting a long time before we ever see a story like it again. In the meantime, for what it’s worth, the Cavalera Conspiracy has announced plans to tour on both sides of the Atlantic performing Roots in its entirety later this year.

As for the Xavante, Graham describes their current situation as dire, but is quick to point out their resilience in the face of adversity.

“If you look at what happens with indigenous cultures,” she says, “they suffer, but they don’t just die. The Xavante is a good example of a group that’s really working hard to keep themselves intact. Things change, of course, but they’re very conscious of maintaining their traditions — musical traditions for example. At the same time, they’re having a really hard time right now because there’s so much development going on. Those lands were taken from them and titled to businesses fraudulently, and they were given very small pieces of land — not enough for them to maintain their subsistence lifestyle. Since the ’70s, they’ve been involved in challenging the government to recuperate that land. They’ve been able to recuperate some small pieces, but the ranchers keep contesting it.”

Graham elaborates further: “Brazil is going through one of the worst political moments for indigenous peoples since the early 20th century. For example, there’s a proposed amendment to the constitution that’s being put together by large landholders. It would basically put all of the decisions about indigenous lands in the legislature, where they’re very subject to lobbying by landholders and agribusiness. Currently, under the constitution, such decisions are under the domain of the executive branch — it’s the president who makes final decisions on whether indigenous peoples will get their lands returned to them, or whether there will be apportioned lands in the first place in the case of uncontacted groups. But if this amendment goes through, it will become extremely difficult for indigenous peoples to get legal titles to contested parcels of their land.”

In a more general sense, however, Graham doesn’t paint an entirely grim picture of the prospects for marginalized or subjugated populations.

“Cultures,” she posits, “are always adapting. Even the subordinate cultures are adapting and changing. They don’t just become extinct unless the actual people get wiped out. Ideas go underground and religious practices become syncretic but people still maintain them in some way. And they change over time. They’re always changing over time the same way that dominant cultures are changing over time and incorporating and adapting elements from more marginalized or subordinate groups.”

“You see this with North American Indians — people think that they’re extinct or that there’s nothing left of them, but in fact they’re still there and they’re asserting themselves. They may not look like they did before, but they’re maintaining a kind of distinctiveness and they don’t see [quite] themselves as members of the dominant culture.”

How will the “little fish” in cultural ecosystems fare now that technology fosters exposure like never before? Are we all headed towards a Blade Runner-esque polyglot future?

“I’ve been writing,” Graham answers, “about this indigenous media project that I worked on with the Xavante. [Graham introduced the first video equipment to the Xavante in 1991 — Ed.] If you introduce media technologies — film and video — there’s the question of whether a group of people like this will just become like everyone else. You might expect that their own cultures will become extinct and they’ll just start consuming whatever junk that’s out there and that that’ll be the end of them.”

“But in fact that’s not what we see at all. Indigenous peoples use the media in their own unique ways. They put together creative products that have a distinct mark of their culture. Their own aesthetics come out in how they edit and what they choose to film. So I think it’s just not the case that we’re headed towards either a flattening — where we’re going to come out with this monocrhomatic culture on the one hand — or this sort of babbling soup on the other hand. People tend to go towards their distinctiveness and use media technologies in unique and distinctive ways.”

“Now,” she adds with a laugh, “the Xavante are all over Facebook! They’re techno-savvy, just like people anywhere.”

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)