The siren song of Hollywood has lured many an aspiring actor and actress to what would become a life of unfulfilled dreams, substance abuse issues and, in some cases, their untimely demise. Rather than gaining screen time and the accompanying fame, these poor lost souls more often than not have found their names splashed across sensational post-mortem headlines that helped ensure their infamy for generations to come.

From Elizabeth Short, aka the Black Dahlia, through more contemporary murders and disappearances of those caught up in the Hollywood underbelly, these individuals managed to make a name for themselves in death alone. Narrowing his focus to the postwar years bookended by the gruesome murder of Short and death of screen icon Marilyn Monroe, Jon Lewis sets out to combine intertwining true crime narratives with the restructuring of Hollywood in the wake of World War II.

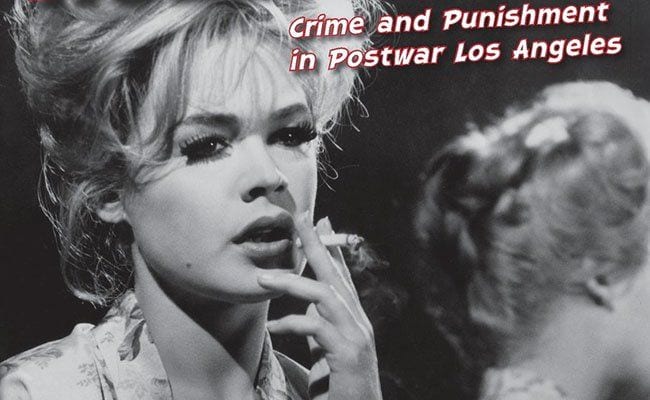

Less salacious than Kenneth Anger’s notorious Hollywood Babylon, Lewis’ Hard-Boiled Hollywood: Crime and Punishment in Postwar Los Angeles relies on quantifiable facts and evidence rather than gossip and here-say to tell the stories of those whose lives were stamped out, often literally, by the cruelly unforgiving urban sprawl of Los Angeles and the surrounding areas. This more straightforward approach doesn’t make these stories any less riveting, however (though it’s hard to beat Anger’s gossip rag prose when it comes to the sleazier side of Hollywood history), shedding light on the postwar years of Hollywood following the demise of the legendary studio system and establishment of a new world order in terms of how success was achieved and maintained. It’s a seedy underworld full of criminals, lowlifes, the mentally unstable, and those willing to do anything to “make it”.

With the apocryphal tale of Lana Turner’s discovery at either Schwab’s Pharmacy or the Top Hat Malt Shop (depending on who’s telling the story) looming large within the Hollywood substrata of wannabe starlets looking to get their big break, it’s little surprise that many of those who met with a sordid end did so while fraternizing in places considered the spot to see and be seen. More often than not, however, as Lewis is quick to point out, these young women found themselves fully immersed in the underworld of organized crime in Los Angeles, human trafficking and drug abuse and any number of other prurient proclivities. With each story dovetailing from one into the next, Lewis presents a linear examination of the more notorious crimes committed by all manner of questionable individuals.

Turner herself shows up due to her involvement with organized crime in Los Angeles, namely her relationship with Johnny Stompanato. One of a number of would-be suitors pursuing Turner, Stompanato would eventually embark on a romance with Turner that ended when her daughter allegedly stabbed and killed Stompanato within the family home. As Stompanato was an associate of Mickey Cohen, this did not sit well within the underworld. It did not, however, stop stars and gangsters from comingling on an all too regular basis. Add to this the rampant corruption within the LAPD and you’ve got a powder keg situation just waiting to explode.

As the book reaches its middle core, Lewis wanders off the trail of his originally stated thesis to take an extended look at the Hollywood blacklist and red scare sweeping the country in the early ’50s. It’s a somewhat odd tangent for a work originally positioned as being a combination of true crime and pop cultural analysis. Yet this slight detour relies on many of the same players featured in both the Black Dahlia case and the Lana Turner/gangster connections. In this, Lewis explores the tangential relationships between the famous and the infamous and the fluid nature of their relationships and social scenes.

While certainly fascinating and a fine overview of post-war Hollywood as it transitioned out of the studio system and into what would become the new wave of American cinema with the rise of the auteur, it proves the title to be something of a misdirect. Much like the scandal sheets Lewis discusses with regard to the fall of many stars and Hollywood hangers-on, the use of “crime and punishment” in the title serves more as a titillating entry point to a broader pop cultural discussion than true analysis of crime and punishment in post-war Hollywood.

Nonetheless, Hard-Boiled Hollywood offers readers a fine entry point into the world of postwar Los Angeles in general and Hollywood in particular. From the end of the studio system to the rise of the auteur, it’s an era full of fascinating stories rooted not only in the bloodshed and corruption described herein, but also the culture-defining moments that led us to where we are now. More Hollywood cultural history than the pure true crime exposé implied by the title, Hard-Boiled Hollywood is nothing if not an enjoyable read for those with an interest in not only Hollywood history, but the cultural and political shifts within the industry that gave rise to a whole new generation of actors and directors.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)