Ildikó Enyedi’s On Body and Soul (Teströl és lélekröl, 2017) was awarded The Golden Bear at the 67th Berlin International Film Festival, and will be Hungary’s submission for the 2018 Academy Awards.

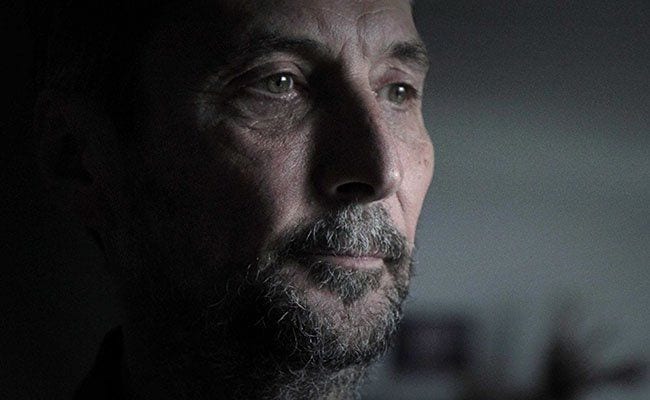

The film tells the story of an introverted man and woman working in a slaughterhouse; Endre (Géza Morcsányi) the divorced, world-weary financial director, and Maria (Alexandra Borbély) the socially awkward and vulnerable quality controller. When they discover they share the same dreams, initially puzzled, the unlikely pair soon attempt to recreate this shared connection in their waking world.

Enyedi’s debut feature My Twentieth Century (1989) was the recipient of the Caméra d’Or at the 1989 Cannes Film Festival. On Body and Soul marks Enyedi return to feature filmmaking after a 17-year break following 1999’s Simon, the Magician. During her hiatus from feature films, her prominent directorial work was the HBO Europe series Terápia (2012-2014).

In conversation with PopMatters, Enyedi reflects on an initial reluctance to define herself, and a missed opportunity for expression. She also discusses the connection between dreams and cinema, and the magic of the movie theatre in the human experience.

Why film as a means of creative expression? Was there an inspirational or defining moment?

I, in fact, chose film quite late. It was after I’d made my first feature film, My Twentieth Century. I was very much resistant to choose anything as a profession. I worked on the borders of culture and mainstream filmmaking because it’s very expensive, and so it was somehow no-go territory. But I enjoyed the complexity of the work on my first feature film so deeply that I just chose film.

What position does On Body and Soul occupy within your body of work?

I can’t really say that I have a career or a clear line. It’s very broken and damaged because I didn’t do what I enjoyed to do for many years. Also, each film of mine came from a very elemental need to share something, and that is why the construction of a film career did not happen.

I think filmmakers should think about this, and I deprived myself of many years when I could have done something fulfilling for me, and perhaps meaningful for others. Although, by being aware of what your work can mean and how you can position yourself in the film industry, you can perhaps forget about your freedom. I’m teaching directing at the University of Budapest and I try to show young filmmakers that it’s necessary, although I must say that in the eyes of the film community, and of the spectators, I am centralised. The warm acceptance of this film with such a natural openness, which has come after 17 years of not being able to make films, somehow speaks against what I just told you about building a career.

What was the impulse that compelled you to re-engage with feature filmmaking after such a prolonged break?

Every day of my life, including the weekends during those 17 years, I was working on a film project, and then finally we started to work on this. I just wanted to avoid making a big splash comeback. This is a very low-key film and when we started, I spoke with my colleagues and I told them, “Listen, guys. This film will probably never go to any major festivals. It’s not connected to any actual currents.” It’s consciously not a strong auteur film. I tried to hide behind my characters because I wanted to let them breathe and to connect directly with the audience. I told them we had to make the film this way because otherwise it just wouldn’t exist. It would have destroyed the film if it had been on a bigger scale or if it was a more showy auteur film.

This is my first film, for example, that I shot on 35mm because today to shoot on film has a sort of auteur quality, but I continue to love it. That’s why we chose a very low-key format and in every sense, we just wanted to make a very low-key film where we just let all of the passion that was simmering under the surface out, and to let the spectators discover it for themselves, should they want to. And in fact, the starting point was this simmering passion and energy, this longing for life and openness beneath the surface.

The drama of filmic storytelling can deprive it of the realism of the human condition or experience. Here, you stray away from dramatics to embrace a subtlety — the way characters will glance around a room or at one another, the little gestures of standing at the window, gazing out and picking up the coffee cup. Even the act of wiping a table or sitting in a room quietly, contemplating loneliness. Does the removal of drama allow film to transform into a prism that reveals a portrait of the realism of the human experience?

I’m so happy you spoke about these details because in our small team I worked with some wonderful people, and everybody was so involved. They understood that just to light the right way, so as to be able to see the crumbs on a kitchen table, and then wiping them away and the water remaining on the table surface were very important elements of our film. And at the slow intervals in the lunch break, when the killing has stopped and people are chitchatting, having a coffee and a cigarette, and some nice music is on the radio, it was very important to capture the faces of the cattle, of the cows standing in silence waiting patiently for the killing to continue.

These so-called ‘passage scenes’ seemingly do not add something to the plot, but they are essential. I was again touched during the shooting as to how naturally and deeply the people with whom I worked with were as involved in the whole story as I was. For example, the prop man and the art director were discussing on not an aesthetic, but a psychological level, which salt and pepper shaker to use. I remember standing behind them as they had a passionate discussion about what a type of material means. For example, why it can’t be a plastic or a metal salt and pepper shaker, and their reasoning was psychological. It spoke about Mária, her life, and in this way it spoke about life and the human condition as you just said.

Aside from its preoccupation with the human condition, On Body and Soul is also interested in the role of dreams in the human experience. C.G. Jung contextualised dreams as a means for us to solve the problems we cannot solve in our waking state, which ties into your two characters experiencing shared dreaming and their attempt to replicate that connection in their waking states. Do you perceive films as being structured on a dream logic?

I’m very happy that you brought up Jung, because from his work the most important thing for me in regard to this film is the common unconscious, which we are so rarely in contact with. In fact, we are effortlessly in contact with it through our dreams, even if we decide yes or no. You can’t decide, you are just yourself. More importantly, you reach out to a level of yourself where you are united with the rest of mankind, where you will have shared something.

In the daylight nearly everything is about differences — what differentiates me from others or us from other groups? I had a wish for my two characters to risk themselves in order to have a full life — not to have that miserable and limited life they chose to have because they were looking for more safety. This is what all of us are doing, perhaps not to the same extreme as Maria, but all of us try to defend ourselves, and by that we limit ourselves.

In your dreams you are together, sharing something and you are fully yourself. It’s like animals that are fully present in every moment of their lives. They just don’t have a choice — they are there, and this is a luxury we very rarely have.

What is the purpose of cinema in our contemporary world? Beyond entertainment, does it possess a deeper universal purpose that exists on both psychological and dreamlike levels?

The function of the movie theatre is changing, and perhaps because of its rarity, and as it becomes rarer to go to the cinema than to consume movie images at home or on your phone, the magic of it becomes stronger again. So somehow we are getting back to the roots, to the early stages of that wonderful luxury to be in a dark room together with unknown people, sharing something with them.

In every cinema hall, a slightly different thing will somehow happen because of the people that are present — how they watch a film together and how they react. I think it is a very important part of our lives to experience the luxury of connecting with one another in a room, connecting through a film with both people that are living far from us, and those no longer living. This is for me a magic place of connection, of being part of these very controversial things, which is humanity on our earth.

On Body and Soul is released theatrically in the UK on Friday 22 September 2017.