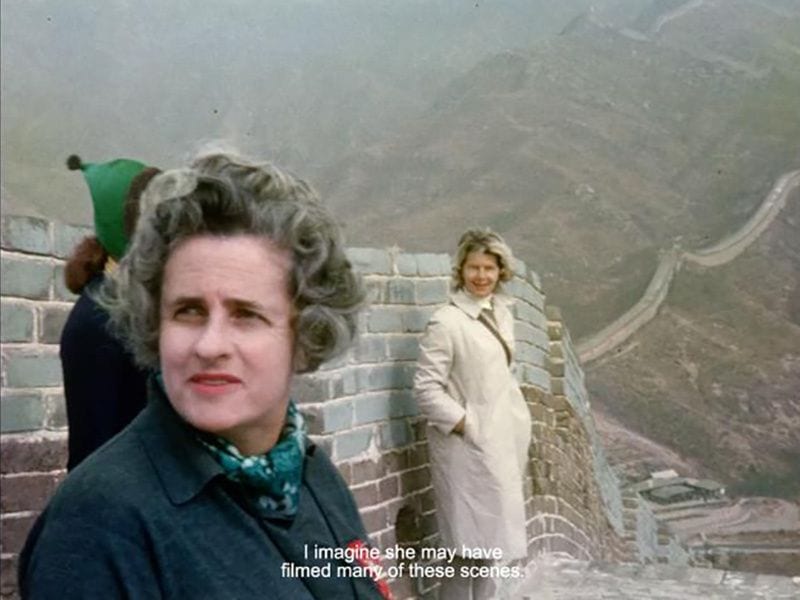

There doesn’t seem to be a glaring reason for Brazilian documentarian João Moreira Salles [News from a Personal War, (Notícias de uma Guerra Particular), 1999 and Santiago, 2007) to combine home movie reels from his parents’ 1966 trip to China with the rest of the amateur footage of the 1968 riots in Paris, Prague, and elsewhere that seemed to portend an utterly changed world order. They don’t on the surface have much in common. Bourgeois students from the Sorbonne rip up paving stones and rocket them through clouds of tear gas towards the police. Salles’ mother in a kerchief and sunglasses tours the Great Wall and marvels at the beautiful artwork and “clangorous din” of Mandarin. But the linkage doesn’t need to be obvious for Salles to make something out of it that can reward an open-hearted audience. This might be intensely personal cinema, à la Chris Marker, to the point of being nearly an internal dialogue. What he’s conveying is universal.

A flickeringly brief theatrical release in 2018 and now available for streaming and on DVD from Icarus Films, In the Intense Now (No Intenso Agora) tracked events from a half-century earlier, but in many ways it resonates with the modern moment. The imagery is densely archival, mostly black-and-white footage shot by unknown amateurs, the odd Marxist collective, or students from the Institut des Hautes Études Cinématographiques (as good a reason as any to declare Paris the world capital of cinema) with the jumpy clarity of something out of World War II. Salles pairs the story of revolution happening in these times with one of a revolution past, where his mother tours through a China swathed in red flags and patriotic hymns, but also excitingly beautiful and new scenes and encounters. It’s a juxtaposition that feels like something of a stretch until the end of the movie, even with Salles’ linking “the joy of the streets” he sees in the giddy Parisian protestors who are having the time of their lives with his mother’s joyful explorations.

The movie’s first half (“Back to the Factory”) starts with the street battles that ripped through Paris in May 1968. As far as Salles tries to explain it, narrating with a sonorous moodiness and marveling wonder, the protests were a sudden flaring crucible in which all the ferment of the Sixties burned white-hot over a few short weeks. At first, the euphoria was bright and shining with the idea that nobody, whether students or workers, was just going to follow orders anymore. It’s a time that in retrospect seems to have taken on an exaggerated import, felt all the more intensely for its brief duration. But rather than placing its flow of events into strictly chronological form, Salles comes at them from another angle, considering not precisely what drove the marchers into the streets and what they hoped to achieve, but how it felt to be there.

Then as now, the politics of protest are as much about emotion as they are about policy. The lawyers and other angered citizens who flocked to airports in an attempt to stop Donald Trump’s attempted Muslim ban in 2017 despised what the act attempted to do. But they also gathered to be together, to experience the joy of resistance together, to feel something that was likely entirely new for many of them. Salles sets out to explore that collaborative rush of excitement, the clash and clangor of conflict, and the various time-healing mechanisms (justification, amnesia, glorification) that crop up afterward and seal up the breach.

As a study of the revolts of 1968, In the Intense Now is more impressionistic essay than history, jumping in its more downbeat second half (“Leaving the Factory”) from Paris and China to the Warsaw Pact’s crushing of the Prague Spring and a funeral procession in Rio de Janeiro for a teenager killed by police. These scenes are linked less by the year they happened than Salles’ interest in exploring the mechanisms of political symbolism they represent. One of his more interesting and melancholic asides, discussing Romain Goupil’s 1982 portrait of ideological disillusionment Mourir à 30 ans (Half a Life), refers to the “precocious nostalgia” of the May 1968 radicals who already believed their lives may have peaked.

Nevertheless, Salles does unearth some notably fascinating historical moments. (Such as the funeral of a Lyons policeman, killed in a confrontation with protestors, which is almost never included in the standard histories alongside the just-as-symbolic funerals of the two protestors who died, one shot by riot police and the other drowned in the Seine while fleeing.) Salles also provides an intriguing insight into some of the major players.

There’s the theatrically opportunistic student leader Daniel Behn-Condit—who impishly refuses to produce demands, noting with a predictive literary flair that the protests were simply “something revealed fleetingly” as proof that their glorious anarchic utopia was possible—and the seemingly tired and aged Charles de Gaulle, the onetime Free French propaganda master who delivers a thunderous radio oration that brings a half-million French into the streets protesting the protests and essentially putting an end to them.

While Salles is most likely sympathetic to the ideals of marching radicals, he retains an eyebrow firmly cocked. He digs up some footage of students gathered outside a factory calling for the workers to join in their fuzzy quasi-Marxist uprising. Looking down from the building’s roof, the workers smoke cigarettes and stare quizzically. Salles notes ironically the gulf of class differences in that exchange, and that some workers referred to the middle- and upper-class students as “our future bosses”.

They knew that this, too, would not last.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)