Hollow House is a three-story mansion in rural Yorkshire built of castellated stone and surrounded by carefully preserved grounds, a meadow, and Eorl Wood, the oldest surviving primeval forest in England. It has a gloomy, implacable aspect – towers and turrets, dormers and gables – and when Charles, a Ph.D. in literature and the protagonist of In the Night Wood, moves in, it is occupied by a steward and a small serving staff.

It is unknown who – or what – else occupies the building and the grounds. Charles’ carelessness had resulted in the death of his daughter, and he and his wife, Erin, are starting over. He is haunted phantasmagorically by his mistakes and obsesses on whether he will ever – or ever deserves to – emerge from the fog of torment.

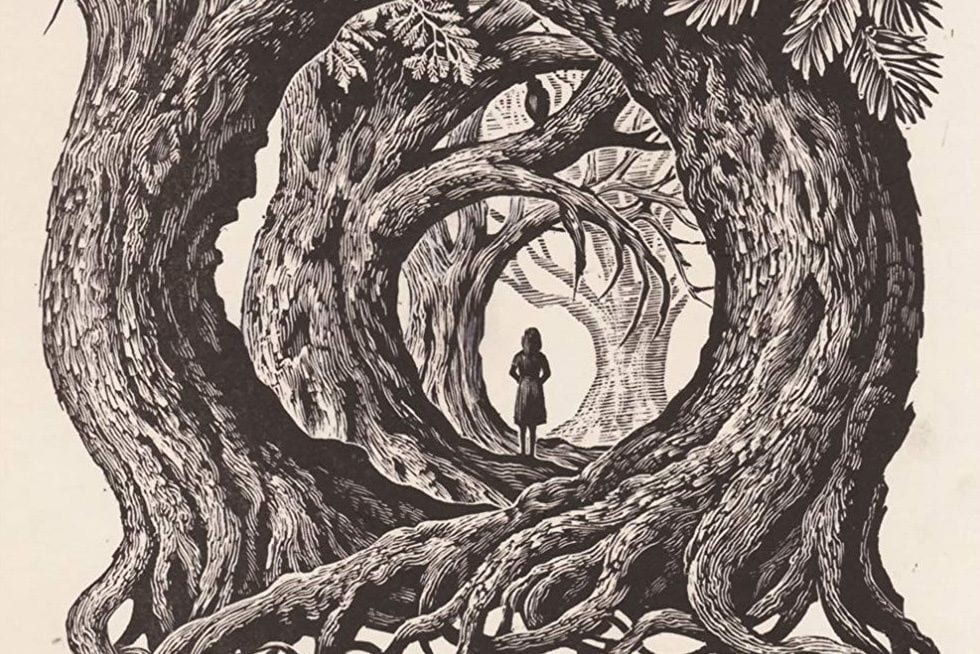

In the Night Wood is genre fiction, clearly, and Dale Bailey‘s adherence to the conventions of the gothic novel is on the-nose. But there are at least two caveats to consider alongside this point. The first is that Bailey exhibits a flair for applying the technique of gothic writing. His adoption of the symbols and themes characteristic of the genre is so thoroughgoing as to be almost encyclopedic. He finds and maintains the right foreboding tone (helpfully established by Andrew Davidson‘s pretty amazing black-and-white cover art), and his writing is immersive and tense. He handles the material artfully.

The second is that a gothic genre exercise is not all that In the Night Wood is. It’s not only a book about puzzles, mazes, and forests. It’s also a story about storytelling itself, a book about books, and writing. There’s an irony at work: Bailey’s use of the well-worn conventions of the gothic novel to tell a story about a story is fitting, as opposed to merely unoriginal or warmed over. Like the characters that Umberto Eco captured in his first three novels, those of In the Night Wood are literary obsessives inspired, baffled, or haunted by texts (or signs, to use the correct jargon from literary theory) – allusions, book-binding textures, codes, cryptic nomenclature, crumbling newspaper, obscure local history, dashed off scribbles, pagan mythology, weird imagery. Charles resembles Causabon of Foucault’s Pendulum (1988), gripped by a threatening text-inspired idée fixe that would appear ludicrous if not confirmed with increasing frequency by the apparent facts of his reality.

But whereas Eco’s themes were language and communication, Bailey’s point is existential. “Perhaps stories had no beginnings or endings at all. Perhaps they simply branched out forever, like rivers, one from another, enveloping you for a brief span, each life a story within a story, intersecting with thousands of other stories to make – what?” Bailey returns to this motif and asks the question again and again. “What if time was a snake that bit its own tail, he said, or a wheel grinding inexorably around the axis of fate? What if what was had been and will be yet? What if you lived inside a story and the story had already been written?”

Eco, of course, was thinking through the same questions. He put it in plain language in the postscript to The Name of the Rose (1980) when he wrote that “books always speak of other books, and every story tells a story that has already been told.” Charles begins to suspect that his story has happened before and will happen again. At the same time, for the educated reader – probably having read Edgar Allan Poe and Mary Shelley, maybe even Horace Walpole and Anne Radcliffe, and at any rate having watched any movie about an old haunted house – the contours of this story will also literally begin to feel familiar. Bailey puts Charles and the reader on the same path to wondering if all our stories are connected, if they all repeat, and if they’re all as old as the Castle of Otronto – or, in this case, as old as the Eorl Wood.

Steer clear of the woods, Charles is warned, people get lost. But Charles goes into the woods. This is the emotional tension of In the Night Wood: the trouble of living inside the eternal recurrence, paralyzed with self-loathing and regret. If you fall far short of loving your fate, can you at least come to accept it? It’s a good question, perennial in Western philosophy, and an apt theme to weave into the heightened emotional drama of gothic storytelling.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)