Brault was part of a team of filmmakers working on a documentary that would expose professional wrestling as a con. They would use slow motion, he told Barthes, to show the mechanics, the sleight of hand, and the misdirection that made it run. “That they don’t really hit,” as Brault later said, “or that they have ways to fall so they don’t hurt themselves.” Barthes was horrified and he told Brault as much. Exposing wrestling would be like exposing theatre, Brault remembered him saying, “the people’s theatre — popular theatre. And you can’t expose that… you mustn’t destroy that!” Taking Barthes’ advice, Brault and his team turned their film, La Lutte (Wrestling), into a celebration of the pleasure that the audience took from getting caught up in the rough spectacle wrestling. A film that showed, in Brault’s words, “what was happening — not what we thought should happen.”

The writers behind publisher Stanley Weston’s line of wrestling magazines would have understood exactly where Barthes was coming from. They filled the pages of Pro Wrestling Illustrated, The Wrestler, Inside Wrestling, and a dozen other Weston-owned titles with absurd, fanciful, and sometimes poignant articles about the wrestling stars of the day. Working in a style that might be called creative journalism, Weston’s staff covered a sport that itself could be described as creative athletics; the blood was real and the punches and injuries were sometimes real, too, but the endings were always pre-determined and behind the scenes, out of view of the fans, almost everyone drank and caroused as friends and co-workers.

“I think we tried to be a part of the whole thing,” says Dave Rosenbaum, who began writing for Weston in 1985. “We weren’t trying to be apart from it. We were trying to be part of it; to add to the experience for the fans, not to take away from it.” Weston’s wrestling magazines had a remarkable publishing run from the ’50s to the ’90s, and some titles remain in production.

The matches Weston’s writers reported on really happened, but more often than not they made-up the interviews, the overheard locker room chatter, and the late-night confessions that their stories centered on. “I specifically remember that the first time I was asked to do a wrestling article, they gave me a bunch of photos, they told me what was going on, and I said, ‘Okay, do you have the phone numbers of the wrestlers so I can get some quotes?’ ” says Steve Farhood, who covered boxing and wrestling for Weston beginning in 1978. “And that was met with a lot of laughs, of course, because I didn’t know that you made up the quotes.” “We gave the fans what they saw and then we took them behind the scenes,” says Gary Morgenstein, who wrote for Weston from 1979 until 1983. “We opened the door. Now, what we were telling them was behind the door we would make up, most of the time. But we gave them something behind the door and it made sense, because we never wrote stories that didn’t make sense. And it connected.”

Stanley Weston began his magazine career in the ’30s, covering boxing as a writer, photographer and cover artist for The Ring. Weston began publishing Boxing & Wrestling in 1953, running his operation from out of his house on Long Island, NY; the art department was in the bedroom and the basement doubled as the darkroom and filing area. Writing after Weston’s death in 2002, Stu Saks, who began working for Weston in 1979, described him as possessing a “twilight zone sense of humor, and [an] urgent need to raise the eyebrows of his audience.” He was fascinated by P.T.Barnum and “relished embellishment,” remembers Weston’s daughter Toby Cone. He loved delivering stories and never shied away from shocking readers or running afoul of good taste. A true magazine man, he published detective magazines, puzzle books, and western-themed magazines alongside his sports titles.

Following the success of Boxing & Wrestling, Weston soon created titles dedicated solely to professional wrestling; Wrestling Revue in 1959 and The Wrestler in 1966. Despite its popularity, professional wrestling was rarely covered in any kind of serious way in major publications and when it was it tended to be with a barely concealed derision. The assumption has always gone that wrestling is the entertainment of choice for mouth breathers and rubes. How else to explain the appeal of an attraction that is so silly, so obviously fake, and that deals in racial, gender, and sexual stereotypes that are so clumsily and tastelessly presented?

A journalist who covered it with any degree of seriousness risked being taken for a fool. This left an opening for Weston. “One thing I know how to do,” he told Newsday, “is I know how to give the public what it wants.” If fans wanted to read about their favorite wrestlers without being made fun of, the Weston titles were one of their only options. As his business grew, he constructed a five-story building in Rockville Center, NY to house it. “Wrestling,” he was known to say, “built the first four floors, and boxing built the fifth.”

In 1970, Weston hired Bill Apter, a 25-year-old wrestling obsessive from Queens. Apter soon became the face of the Weston magazines to the public through his near-constant presence at matches in New York’s Madison Square Garden and later, on cable television. During his over 20 years working for Weston he wrote news, managed freelance writers and photographers, shot pictures at ringside, and guided the direction of stories. Most importantly to the magazines, he gained the trust of local wrestling promoters. “[Bill] was very, very trusted in the industry,’ says Saks. “That was of huge importance to us, the fact that he was accepted by the industry and trusted by the industry. So they would tell him things that they wouldn’t tell someone they didn’t trust.”

Weston’s magazines approached wrestling from within the confines of kayfabe, the pig latin word for wrestling’s code of secrecy. It mandated that anyone involved in wrestling’s otherwise closed-door world portray every aspect of it as nothing less than on the level. “Keeping the family secret is what [kayfabe] really meant,” says Apter. “Magicians kayfabe the way they do their tricks. They don’t break the unwritten code and let the public in on how the business of trickery operates. It was the same back when kayfabe was the unwritten law in pro wrestling.” “I still get a little skittish talking about the kayfabe stuff because of all of the years that I didn’t discuss these things with anybody,” says Joe Bua, who wrote for Weston from 1982 until 1985. “Even at the magazine we never talked about how wrestling was fake. At the office we did but you know, when you saw fans at shows and stuff, ‘uh uh’. You had it as close to the vest as the wrestlers did at the time.”

In the pulpy pages of a Weston magazine, the snickering question that was invariably at the center of almost all media coverage on pro wrestling, the question of how people who watched wrestling could possibly take it seriously, never even came up. If Captain Lou Albano claimed that Mr. Fuji was a direct descendant of Japanese royalty, or Dusty Rhodes said he’d been blinded, the Weston magazines wouldn’t contradict them, they’d use the statement as a jumping-off point for a 1,000 word article. In the stories and columns that filled Weston’s titles, the exaggerated emotions, histrionics, and broad gestures that helped create what Roland Barthes described as wrestling’s “great spectacle of suffering, of defeat, and of justice,” were just the beginning of the story. Weston’s writers took storylines that were already overstuffed with pathos and melodrama and filled them up even more.

“Imagine if you’re reading a Superman comic,” says Rosenbaum, “and all of a sudden one of the characters says, ‘Superman’s not real.’ Nobody wants to read about that. You don’t want to ruin the fantasy. Most people enjoyed wrestling because of the fantasy and role playing and getting into it. It wasn’t our job to ruin it. It was our job to help it.” “To believe in something doesn’t take much,” says Eddie Ellner, who began writing for Weston in 1984. “That’s just the human condition. It hasn’t really changed, ever. A little bit of that idea of ‘a sucker born every minute’ is because the sucker is really willing to suspend their sense of discernment in the hopes of seeing a miracle.”

The entire world of professional wrestling was real but also utter fiction at the exact same time. “[With wrestling,] you have several different jetstreams of unconscious attractions,” says Ellner. “First of all, you have the whole good versus evil, that visceral base desire to root for somebody good to conquer somebody bad. Or secretly root for somebody bad to disrupt the good. You have a phenomenally and bizarrely athletic group of people doing really strange things, but whether it’s fake or not they’re really doing it. It may be pre-arranged but they’re actually executing, right in front of people.”

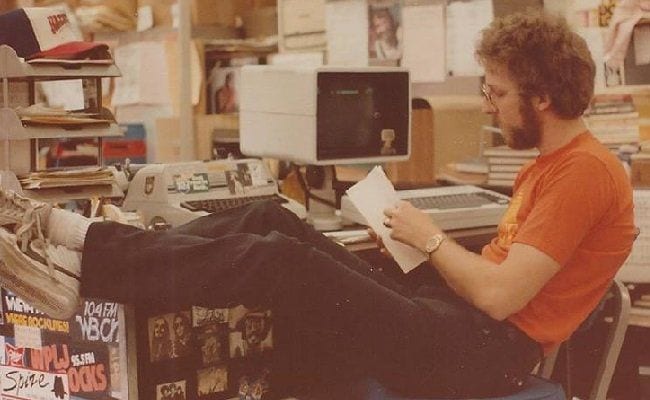

Writer Craig Peters at his desk (Photo Courtesy of Craig Peters)

“This is where I came to understand [wrestling],” says Craig Peters, who joined the Weston magazines in 1981. “I came to the conclusion that everyone knows there are certain things in wrestling that are fake. These guys don’t hate each other as much as they seem to. Okay, I get that, that part’s fake. On the other hand, that guy’s really bleeding. If he jumps off the top rope, he’s going to jam his knee. Knee injuries in wrestling are huge. There is impact. A 200 lb object hitting the mat from 12 feet, that’s physics. That’s real. So you know that there’s stuff that’s fake and you know that there’s stuff that’s real. You just don’t know where the dividing line is, and that dividing line changes all the time. It’s in the dance of that dividing line that wrestling becomes interesting.”

The writing in Weston’s magazines followed the same loopy logic. It was all a constantly shifting mix of fact and fiction, and the challenge for the conveyors of it was to keep the fans believing in something that wasn’t necessarily there. “In essence what we did was, we reflected what the business was all about,” says Saks. “The business was all about portraying wrestling as a sport. And we didn’t deviate from that in any way. We wanted to give the impression that wrestling was just like any other sport with a little bit more colorful characters.”

Weston began expanding his full-time staff in the mid-’70s and reducing his reliance on freelancers. “The reason that our magazines did as well as they did,” says Peters, “is because the whole staff was made up of people who were journalism majors in college, or were English majors who worked on the college papers. People were sort of publishing professionals first and wrestling fans second.” To avoid drawing attention to the fact that so few writers were contributing to the magazines, many wrestling articles from the ’60s and early ’70s did not carry bylines. Looking to create more personality in his magazines and to connect more directly with readers, Weston’s editor-in-chief Peter King, worked to change that.

King gave each editor a bylined column. The writers became characters in each other’s pieces. They portrayed themselves as traveling the world, staking out dressing rooms, and risking physical harm in pursuit of the latest wrestling news. “I had a column called ‘On The Road,’ ” says Farhood. “So, from the comfort of my desk I would go on the road to wherever and tell a story. So, I write a column that I go to Minnesota to spend a weekend with Ric Flair, the most hated man in wrestling, to get a feel for what he’s really like. And I get there, and I don’t know what the hell made me think to write this, but I wrote that his best friend, and I made up a name, died just as I got there. So I say to Ric Flair, ‘Ric, this is not a good weekend, this is not a good time. You’re mourning, I’ll go home.’ He says, ‘No, I want you to see the real me.’ So over the course of the next three days that I’m ‘there,’ I find him to be an incredibly sensitive guy and a great friend. He’s saying all the right things, being there for the family; all that stuff. So the bottom line is Ric Flair wouldn’t know me if he spit on me, to this day or back then. That doesn’t matter. I got more letters from readers about that column than any boxing column I’ve ever written, and people were saying, ‘I’m a fan now. I never realized he was that sensitive.'”

Why Interview a Fake Person?

As long as they stayed within the current storyline that the wrestler was involved in and didn’t invent anything that the wrestler might not really say, anything went. “I’ve been asked that question about making up quotes,” says Rosenbaum, “and people say it’s horrible and I say, no, it’s not. I’m interviewing Ric Flair the character, not Ric Flair the person, okay? So if I know who Ric Flair the character is and the way he speaks and what [promoters] might be doing with Ric Flair the character, what’s the difference between me making up the quote and speaking to Ric Flair the character directly? Why would I want to interview a fake person? It would be like saying, ‘Go interview some character on a TV show.’ What does that mean?”

Stories were conceived with all of the writers gathered around a desk, pouring through the most current photos. Once sets of pictures were collected, headlines would be brainstormed to fit each set. Once they had the photos and the headlines, each writer broke off to write the copy to fit the headline. “It was a very loose, very collaborative atmosphere,” says Peters. “Bill [Apter] would pull out his manila envelope full of photos; ‘Well, we have eight photos of Hulk Hogan versus Superstar Graham.’ ‘Alright, what are we going to do?’ And people just start throwing out ideas, ‘Well, how about if Hogan got pissed at Graham for this reason?’ ‘Well, maybe Graham pissed off his mother,’ or something like that. ‘Alright, that’s good!’ Then people start throwing out headlines; ‘The Maternal Insult That Enraged Hulk Hogan.’ You can go back and look at the headlines and reverse engineer how we might have come to that.” “You look at these people and you think, ‘What would be fascinating about them?'” says Rosenbaum. “And the great thing about writing for wrestling is that you can make it happen. Let’s face it, it’s the only area of journalism, or writing, where you write the headline first and then you write the article.”

Characters already exaggerated and larger than real life, with their bleached hair, massive arms, or barrel chests and names like The Bruiser, The Destroyer, and the Road Warriors, were given inner fears, secret shames, and regrets that haunted them. Many articles featured them alone with their thoughts, or in hilariously mundane settings. There was Larry Zbyszko, abandoned by his friends, preparing food for a dinner party no one would attend. There was the Masked Superstar going to his therapist’s office (“Without warmth, without a reason to awaken, a man can slowly die. Inside, Superstar is wasting away. His torment is unnerving.”) “Hatred In My Heart,” a 1981 article on Harley Race, found the tattooed world champion reflecting on his decision to live the life of a rulebreaker; “I’ll never forget the nights I spent alone on the road, pondering my existence. I turned to philosophy. I turned to astrology. I couldn’t find the answer. I knew deep in my heart that hurting people was wrong. But I also knew I wanted to be somebody in this life. I wanted to be a champion.” “You had to humanize them,” says Morgenstein. “The whole drama of [wrestling] was that there were good guys and there were bad guys and they had their feuds. So, the question if you’re a writer is, ‘What’s their motivation?’ “

Stu Saks with Dusty Rhodes (Photo Courtesy of Pro Wrestling Illustrated)

Stocked in supermarkets, newspaper stands, pharmacies, convenience stores, truck stops, and bookstores, Weston’s magazines served as free publicity for the wrestlers. Through the magazines, they gained national exposure at a time when that would have otherwise been impossible. Fans in New York or the Carolinas could read about what was happening in California and Oregon, areas they would otherwise have never been exposed to. “I had no idea there was any wrestling going on anywhere else,” says wrestling historian Mark James. “There was no cable. It was whatever you saw local on the antennas was what you got. [The wrestling magazines were] the cable TV of the time.” Young fans collected them like other kids collected comic books and baseball cards. And by the early ’80s, new issues of the growing line of Weston wrestling titles would appear in the magazine racks almost weekly. “At our height, we had a deadline every single week,” says Saks. “We were churning out a lot.”

With crisp photography and carefully constructed covers, the Weston titles fit easily in magazine racks alongside Time, Newsweek, Mad, and Rolling Stone. With a growing number of magazines to fill each month, the stories now had to be produced even more quickly than before; lead writers could be responsible for as many as 3,000 words a day, day in and day out. “My personal record was six stories in one day,” says Peters. “You didn’t start a wrestling piece on a Monday and finish it on a Wednesday,” says Farhood. “You worked on it on Monday and finished it on Monday.” And unlike magazines in more traditional genres, Weston’s relied on newsstand sales for survival. Most magazines are supported through advertising sales, with publishers offering subscriptions at a deep discount from the cover price to build a large reader base. But because advertisers largely shied away from being associated with pro wrestling, the money from the ad sales they could attract, like instruction manuals on bodybuilding and dating, vitamins to restore hair color, or books on “The Magic Power of Witchcraft” were “more or less gravy,” says Saks. Newsstand sales regularly accounted for over 90 percent of their overall sales, an almost outrageous percentage.

To add variety to a staff of writers that was almost made-up exclusively of New York guys in their 20s, new writers, like the no-nonsense female journalist Liz Hunter and the seen-it-all barfly Matt Brock, were invented and brought to life. “It was easy to be Liz Hunter,” says Bua. “Liz Hunter was a feminist and she was a ballsy girl. And it was easy to write for her. I don’t know if it was some of my best work but I had the best time writing Liz Hunter.” These fictional writers were so integrated into the magazines that former readers still question which of the writers were real and which were Jo Bob Briggs-type inventions. No writer’s existence is more debated than Dan Shocket, remembered by readers for columns where he adopted a shock jock-like persona to taunt and antagonize fans, calling them illiterate, mindless and ignorant. Good guy wrestlers were dismissed as “wormslime” and accused of paying off referees. Bad guys were celebrated for their integrity and refusal to pander to the crowd.

Shocket was very much a real person and is consistently remembered by the other writers as ambitious, eccentric, and occasionally obnoxious, often smoking cigars in the wall-less writer’s bullpen that they shared. “Probably the closest analogy to Dan that I can think of, in the writing world, is Harlan Ellison,” says Peters. “[A] very opinionated, take no prisoners, no bullshit kind of attitude and Dan was a little bit of that type.” While covering wrestling for Weston, Shocket was also a featured writer in Al Goldstein’s Screw magazine, turning-in 1200 word reviews of porn movies along with features on politics, sex, and culture. “You know how Cher called Sonny the most interesting character she’d ever met,” says Bua. “If you could put Bill Apter and Dan Shocket together, that would be the most interesting person I ever met.”

For Weston’s Sports Review Wrestling line, Shocket mixed sex and wrestling together as one of the main writers responsible for a monthly run of sweaty-palmed articles based in a wholly invented underground circuit of woman-on-woman apartment wrestling matches. Theo Ehret, the house photographer at the Grand Olympic Auditorium in Los Angeles, contributed the photographs of grappling women. Ehret worked out of his Sunset Boulevard studio, using a rotating supply of local models wearing bikinis that he purchased from Frederick’s of Hollywood. “I made a pin-up board with my pro wrestling photos and had them imitate the moves,” said Ehret in an interview for Exquisite Mayhem, Taschen’s 1991 collection of his work.

“They didn’t know what to do and I’m not an expert either. I picked out some wrestling photos and things started to develop from there. I would tell them to just move around and get into the hold and fall over each other, or do whatever. We would try it once, and if it looked good, I would say, ‘Okay, repeat the same pose,’ and I would shoot it. We went from one hold to the next.” (One of his models turned out to be Lynne Margulies, Andy Kaufman’s partner in the 1980s and director of I’m From Hollywood, which documents Kaufman’s professional wrestling career. “When [the issue] came out, Andy and I were in New York and at the newsstand and he said, ‘Look, there it is!’ and bought up a bunch of them,” Margulies remembers.)

Dan Shocket at his desk (Photo Courtesy of Pro Wrestling Illustrated)

Like his cover features for Screw, Shocket’s apartment wrestling stories ran for thousands of words. Most involved awkward juxtapositions of class and gender, and all happily laughed in the face of moralism and good taste. The pieces typically included elaborate backstories on the women involved in each match. There was Kelley, the harried secretary versus Triana, the struggling actress, both hired to provide the entertainment on the last cruise of “one of the world’s most sumptuous luxury liners.” There was Belinda and Pamela, who brutalized each other in a penthouse on the edge of Central Park for the taboo entertainment of Manhattan’s elite.

“[Apartment wresting] is probably the most outrageous thing that Stanley Weston ever [published],” says Bua. “These events happened in what we call ‘luxury buildings in big cities throughout the world.’ And what was hilarious was when you looked at the photos, the furnishings that these models were in front of were just so pedestrian.” Shocket died in 1985, at the age of 35. In a 1984 editorial in Screw, he wrote about undergoing treatment for the cancer that would eventually kill him and wondered if his illness was God’s payback for an article he’d written satirizing the birth of Jesus.

By the mid-’80s, wrestling was quickly changing from a regional phenomenon into mainstream entertainment, with most of the public interest focused on Hulk Hogan and Vince McMahon’s WWF (now WWE). McMahon’s promotion had expanded from putting on wrestling shows around New York to cross-country tours, branded toys, ice cream, video games, and Saturday morning cartoons. Through syndication, the increased availability of cable, and pay-per-view technology, he sent his programming nationwide. McMahon’s stars appeared on late night talk shows, MTV, and Saturday Night Live.

To drive sales of his branded magazine, McMahon began restricting access to his contracted wrestlers and banning photographers from other wrestling magazines from shooting pictures at WWF matches. To survive, Weston’s writers had to be even more creative. Denied access to McMahon’s wrestlers, a new character, “noted psychologist” Sydney M. Basil was invented to comment on them. Banned from photographing matches at ringside and sometimes shut out of entire arenas, photographers adjusted. “There is a story that sounds apocryphal, I believe it’s not, of one of our photographers smuggling the camera into Madison Square Garden like it was a hero sandwich,” says Peters. “Like the lens was inside the bread of the sandwich and then the body of the camera was stuffed down his pants. Then he went in, got his seat, he had the long lens, and he sat up and got the pictures from the stands.”

As McMahon’s business grew, the wrestling world itself seemed to become almost deadly serious. Long-standing regional promotions were driven out of business, and a string of wrestlers and promoters died violent deaths. Weston’s magazines were one of the few national outlets to cover the deaths of Frank Goodish, who wrestled as Bruiser Brody and died after being stabbed by a fellow wrestler in San Juan, and the Von Erich family, who endured the deaths of brothers David, Mike, Chris, and Kerry between 1984 and 1993. “We were a kayfabe magazine, and we definitely had a lot of fun with things, but there was a reality aspect too,” says Rosenbaum. “When a major figure in wrestling dies, you just can’t ignore it. There were moments where you go, ‘Okay, we’re dealing with real life here.’ ”

The writers ran an in-depth interview with David Schultz, the wrestler who struck John Stossel during a taping of 20/20 after the reporter asked him on-camera if wrestling was fake, and interviewed executives with Turner Broadcasting following Ted Turner’s purchase of Jim Crockett Promotions, a North Carolina-based wrestling company. “I think reality was starting to force itself into this fantasy world of pro wrestling,” says Peters. “It was all fun and games and great angles and then reality started creeping in. It was an interesting dynamic at the magazine, where things were happening in the business and the magazines themselves had to necessarily grow up and change because of it. For certain stories we couldn’t just make up the quotes anymore.”

A 1987 piece written by Eddie Ellner beautifully blended the kayfabe sensibility of the Weston magazines with a real-time commentary on the changing state of wrestling. Ellner placed himself and the fictional Matt Brock in the last row of the Pontiac Silverdome during Wrestlemania III, the largest professional wrestling event ever held in the United States; “The nostalgia of pro wrestling conjures seedy visions of smoke-filled arenas, crooked promoters, and fat, unsightly participants,” he wrote. “Today, the sport is streamlined: conditioned athletes, modern travel, generous promoters … yeah right! Remarkably, little has changed about the sport since Matt Brock’s prime. Wrestlers are still abused, without benefits or pensions. Except today the slice of the pie that they are denied is much bigger than it used to be.”

By the end of the ’80s, the WWF was successfully in the mainstream. In order to free itself from the regulatory oversight of state athletic commissions, WWF officials openly admitted in court that wrestling was much more entertainment than competition. Adherence to kayfabe slowly dwindled as fans increasingly became as aware of the business of wrestling, the contract negotiations, ratings, and buy rates, as what they saw in the ring. “It wasn’t a sudden thing, like I recall,” says Peters. “The breaking of kayfabe was happening gradually. It wasn’t like, ‘Holy crap, he broke kayfabe. Everything’s different now.’ There was none of that. It was sort of like, ‘Well, we can talk a little more about this stuff now.’ We, as a magazine, kept kayfabe longer than anybody else.”

In 1992, after a lifetime spent in magazine publishing, Weston sold his company to Kappa Publishing, a Pennsylvania-based company that made its fortune in crossword puzzles and word games. The staff willing to make the move were relocated to Blue Bell, Pennsylvania, a small town 45 minutes outside of Philadelphia. Weston died in 2002. His papers are now part of the Joyce Sports Research Collection at Notre Dame’s Hesburgh Library.

Individual magazine titles slowly went out of print but Pro Wrestling Illustrated, a title begun in 1979, still remains in production and new issues can still be found on newsstands every other month. “Today it’s totally different than it was,” says Saks, who became editor-in-chief in 1987. “Most of the stuff we do today is direct reporting. We speak to the wrestlers all of the time. Most of the stories are done as if they were being done by any other publication, because we’re not angle-oriented as much as we were. Now we get much more into life stories, and stories about them as performers and as people, so it would be counter-productive to do the stories now like we did them then. Everybody has a story, including the wrestlers. And they know what their life story is, and they can tell it a lot more interestingly than anything we can come up with.”

Saks is in his third decade of publishing magazines, and he’s kept Pro Wrestling Illustrated in print through seismic shifts in the businesses of both publishing and wrestling. The magazine’s offices now sit on the top floor of a two-story brick professional building. Stacked floor to air vents with binders, boxes, books, and photos, its storage closet holds what is likely the only complete archive of the Weston line of wrestling magazines. In the filing cabinets, there are folders that have the same typewritten labels that were created by Bill Apter when he first organized Weston’s files back in 1970. Taken together, it’s over 70 years of professional wrestling and magazine history.

“I think wrestling was looked down on, so the magazines that were part and parcel in making wrestling popular and bringing it to a wider audience would also be discounted a little bit,” says Morgenstein. “But we didn’t care. We knew we weren’t Sports Illustrated. But yet, we had high standards. We didn’t write down. We didn’t say, ‘Well, the fans don’t read New Yorker magazine so they’re not going to know the difference. We would write intelligently. We would make intelligent references, sometimes. If people didn’t get it, they didn’t get it. We didn’t reference Kierkegard. We’d pull ourselves in, to a point.

“But we’d reference current events, history, or pop culture things happening,” Morgenstein continues. “We tried to challenge them a little bit. We always wanted quality. We always wanted the best. And I think that’s what’s hard for people to grasp. They go, ‘Oh, well wrestling is dumb.’ But the people who wrestled worked very hard and were very skilled. And the people who produced the shows were, also. And the people who did the magazines, it was the same way.”

“I think that the Weston wrestling magazines in the glory years were something really unique in publishing history and they probably don’t get the credit that they deserve for being that,” says Peters. “The way that they were produced, the way that they approached and treated wrestling, the way they respected the readers, respected the wrestlers, and the gumbo of sensibilities that came together for a bunch of years in those magazines, they were just great. They were fun to write, fun to read. There was supreme magazine entertainment going on there for a decade or more.”

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)