What are the chances we’ll ever see another era like the ’70s when the financial health of the music industry meant that companies had the freedom to support artists simply because they believed in the music? Of course, there is the more cynical explanation which holds that record labels were so successful during that decade, they needed ‘failures’ as tax write-offs and merrily signed up niche artists left, right and center. But whatever the case (and it may be a mixture of both explanations), time and again, major labels carried artists who didn’t sell huge amounts, often supporting them even after four or five underselling but critically lauded releases.

For many years now, I have made it my business to explore not only the mainstream but also the fringes of the singer/songwriter movement that occurred on both sides of the Atlantic from the late ’60s onwards. I learned early in life that success and quality are not necessarily commensurate and so it has proven; I have stumbled on some of the best popular music in the world by not making the mistake of confining my listening to music made by famous people. It strikes me as terribly unfortunate that so many people restrict themselves either to music on radio chosen by someone else or to music made by celebrities. One of the things that has facilitated my exploration is the prevalence of Japanese CD reissues of the lesser-known albums of several pop eras. These are generally limited-run CDs that come and go quite quickly. Usually within a few years of their release, the prices shoot up to around $50 to $70. With that in mind, I am flagging up a particular reissue while it’s still comparatively affordable. It deserves to be better known.

Like so many of the best singers/songwriters, Karen Alexander was on David Geffen’s Asylum label. People may think that the rediscovery of Judee Sill in the 2000s was the beginning and end of the hidden treasures issued by that label. They’d be wrong. In fact, many of us who’d been listening to Sill in the ’90s or earlier raised a sardonic eyebrow as journalists began constructing a Nick Drake-style death-cult around her 30 years after she’d recorded. Perhaps some of us knew that if you plundered the Asylum vaults for examples of unfairly overlooked genius, you’d find much, much more.

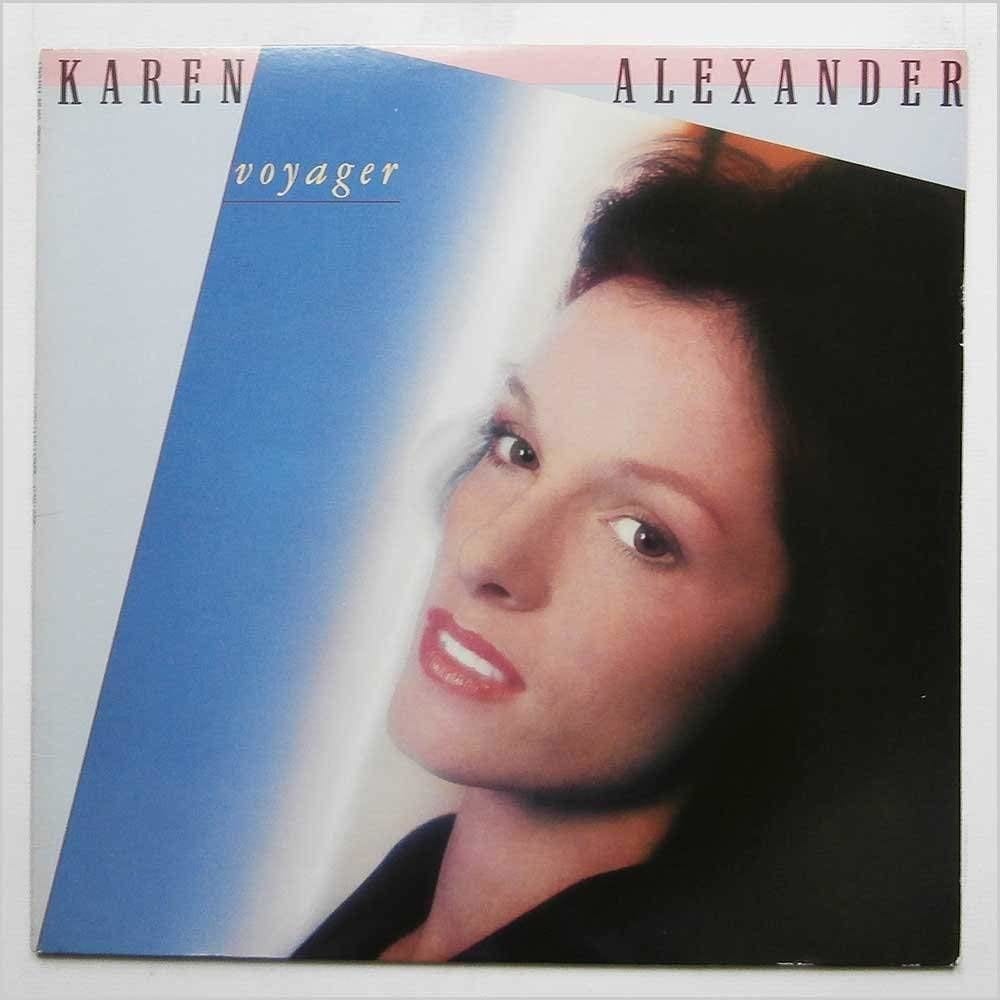

Alexander’s first album, Isn’t It Always Love (1975), is certainly a work of uncommon quality. Asylum supported her even when it became obvious that for various reasons she would be unable to tour behind or even significantly promote her own work. She was expecting her third child when she made Isn’t It Always Love, and her life was divided between Iran and the US (in 1999, Alexander’s daughter, Tara Bahrampour, wrote a memoir, To See and See Again: A Life in Iran and America, published by Farrar, Straus & Giroux, about her bi-cultural upbringing). They continued to support her through a second album, the pleasant but comparatively muddled Voyager (1978). Voyager suffers from an uncertainty, a sense that the team involved weren’t sure what kind of album they wanted to make.

What, with a few exceptions, distinguishes the singer/songwriters of Alexander’s era from those of today is that the former had immersed themselves in a far wider variety of types of music. The songs on their albums were informed by everything from multiple eras of classical music to ’30s and ’40s pre-rock songs to soul, jazz, ragtime, and folk. They grew up in families where everyone had a piano and where relations played music together, a greater proportion of schools had orchestras, choirs, and vocal troupes, and music appreciation classes were a normal part of a young person’s development.

By comparison, a singer/songwriter of today is highly likely to have only been exposed to popular radio playlists. They may know no music any older than late 20th century pop. And it shows – it shows in their melodies and their lack of fluency with the language of chords (and this applies even to those coming up through stage schools). I would encourage anyone and everyone to listen to Isn’t It Always Love. You’ll hear influences ranging from the Andrews Sisters to Neil Young to Middle Eastern folk music. It’s a terrific album, beautifully sung, arranged (David Campbell) and produced (Chuck Plotkin, a childhood friend of Alexander’s, who made equally excellent albums for Wendy Waldman and Steve Ferguson). Within a year or two of its release, Twiggy and Julie Covington had begun to record Alexander’s songs.

Although Alexander’s album is rich, detailed and eloquent enough to speak for itself, I spent an hour with her via Skype earlier this year, eager to hear what she had to say about it and her afterlife as one of the lesser-known acts on the premier singer/songwriter record label of the ’70s. I was struck by how much she still resembled the Voyager sleeve photographs of 40 years ago.

“My family was musical,” she says, “but in those days a lot of families were musical. My grandfather would play the piano, and we would all sing parts. I think it comes from church, back in the day. That’s what people did, even in my parents’ era. They sat around the piano and sang, and they sang in harmony. My mother was a very good, very accomplished classical pianist and never did anything with it but played at home. It was a large family, and when her uncles and aunts showed up, everybody sang, at least in three or four parts. It was a natural thing. I also grew up hearing a lot of classical music, especially Bach.”

In her 20s, Alexander married Esfandiar Bahrampour, whose work took the young couple to Iran. They settled in Tehran and started a family. “I used to come back most summers. All the foreign wives would charter a plane and fly to the States and stay for a month. One summer, I saw my old friends and one of them was Chuck [Plotkin]. He said, ‘I’m doing music now, and I have a studio.’ He gave me a couple of albums and said, ‘You could do this! I remember your songs from the school song festivals’. And that was it. It was not something I had thought of doing. It had never occurred to me, but it sounded fun.”

As a kind of dress rehearsal and an opportunity to familiarise herself with the recording process, Alexander became part of the cast of Wendy Waldman’s first album, Love Has Got Me. Waldman, like Alexander a native Angelina, had been part of Bryndle, a folk-rock group with Andrew Gold, Karla Bonoff and Kenny Edwards. The band had made an unreleased A&M album before calling it quits. Waldman was the first of the four to get a solo career under way, signing with Warner Brothers. Chuck Plotkin was commissioned to produce the record, with Alexander one of the backing vocalists. Although it wasn’t a bestseller, Love Has Got Me got a long rave review in Rolling Stone and remains one of the most extravagantly creative and beautiful examples of singer/songwriter music. “A great album,” Alexander concurs. “It just came to her so young. It showed all her talent.” Alexander had another opportunity to gather experience that same year when she sang on Maria Muldaur’s smash-hit debut album, also a Warner Brothers project.

Alexander’s innate grasp of harmony would end up having a direct impact on how she composed her first album. Although she’d had a few guitar lessons, she didn’t have an instrument at her command. Where many a songwriter, especially today, might merely compose the melody of a song and allow other people, uncredited, to make the crucial decisions as to the chords and counterpoint melodies happening underneath, Alexander could hear the chords she wanted and made demos using her voice to construct them. “I had two tape recorders, and each one had two tracks, and I’d flip back and forth. Because I didn’t have an instrument, I had to show whoever was listening what the chords were. I didn’t want them to get it wrong; I didn’t want it translated into a chord that wasn’t the chord in my head. So I ended up going oo-wa-wa in the background of every song. It saved a lot of trouble.”

One happy side-effect of this method of composing and demo-making was that when Alexander’s album came to be recorded, it seemed entirely natural to keep the close-harmony arrangements, even once instruments and orchestrations had been added, and make them a distinctive feature of her sound. But before all that could happen, she had to have a record deal. “I had pretty much given up on that,” she says. “I came to LA two summers in a row and stayed for eight months trying to get a deal. I was always on the verge. I would be told, ‘any minute now, so and so is going to sign you’. It would never quite happen. I would go to Capitol Records and sing. Go to the Troubadour and sing, showcasing my songs. I went back to Iran and decided I was going to paint and then Charlie [Plotkin] became an A&R person at Asylum and he said, ‘Now you have a deal!'” Alexander decided not to disclose her pregnancy to the company. “I thought, ‘What if I tell them? Maybe I won’t get to make this record’. So I didn’t say anything to anybody.”

Plotkin surrounded Alexander with some of the finest musicians and arrangers that America had to offer in the ’70s – Dean Parks (guitar, ukulele), Andrew Gold, who had also become an Asylum artist that year (12-string guitar, electric guitar, recorder), Matthew Betton (drums, tack piano, vibes, percussion) and David Jackson (acoustic/electric bass, tuba). Strings and woodwind instruments were arranged by David Campbell (father of Beck), as distinctive and excellent an arranger as his contemporary, Paul Buckmaster.

Since Alexander had written the album in two settings, half in Iran and half on jaunts back to California, during which she either stayed with her parents or at a motel, the songs were a mix of childhood reminiscences (“Brown Shoes”, “Fish in the Sea”, “Home to California”) and more international-flavored observational songs (“Hotel”, “Russian Lady”, “Baghdad Ragman”). The America-set songs are whimsical and wistful, combining folk and jazz, with light, feathery arrangements. “Brown Shoes”, a frisky, witty, pre-rock, Charleston-era delight, introduces Alexander’s intricate close-harmony singing. It fizzes with dotted rhythms, internal rhymes, and pay-offs both melodic and lyrical (“Oh Lord help the poor man that I love more than those shoes”). There are skilfully written throwbacks (“Watch Out”) that recall vocal groups like the Andrews Sisters and acoustic folk songs that are Neil Young-inspired.

The Iranian/international songs are particularly ambitious and sophisticated; “Baghdad Ragman” with its haunting, twisty saxophone, “Russian Lady” a four-minute epic novel, and the intrigue-rich “Hotel”. Alexander makes masterful use an array of melodic and harmonic ideas of varying provenance. Perhaps “Baghdad Ragman” with its elaborate, byzantine melody, set to a rapid-fire description of townspeople (Hossein the barber, Hassan the butcher, Hakim the doctor, Hamid the druggist) and the clandestine romance between the ragman and an unnamed woman, is the album’s masterpiece. But it’s hard to choose. If you listened to this album without paying attention, it might seem merely pleasant. But it’s not hyperbole to posit that this somewhat ‘lost’ collection is easily on a par with more celebrated Asylum albums by Joni Mitchell.

Isn’t It Always Love sounds like the work of a fully-formed, highly confident writer but, says, Alexander, far from it – she was learning as she went along. Where many people work on their music while consciously avoiding listening to anything else, lest it exert some kind of sub-conscious influence, Alexander fashioned her songs by the exact opposite method. “Chuck gave me albums and said, ‘Listen to these and see how they construct songs. This is what’s happening now’. I gave the kids to my mother and every day I tried to write a song. I’d start one and then finish it the next morning. I remember listening to a Neil Young album in my sister’s bedroom and then writing “Fish in the Sea”. I can see how that came from Harvest. And ‘A Little Bit More’ came from listening to Randy Newman. I wanted to write a song that took an idea and pushed it into over-the-topness [the song’s narrator wants her partner to be more demonstrative, but to an absurd extent]. I see now that I was learning by the seat of my pants, saying, ‘Ok. Let me try this song this way and that song that way’. I would start by listening to a song and then I would write one. That’s how it happened. At the end of five weeks, I had enough songs. I began to think of myself as someone who could do this.” Tacked on, presumably for its singles-potential, was the album’s sole contribution from an external writer, Karla Bonoff’s “Isn’t It Always Love” (here, it’s given a quasi-Hawaiian treatment quite different to the more pop arrangements that would later be recorded by Bonoff and Linda Ronstadt).

Alexander describes the album as ‘message-less’. “It’s just me, happy to be in an exotic environment, singing about it, trying to think of something to say.” In seeing it that way, she hits upon one of the reasons it’s so good. It really isn’t trying to sell you anything. It’s not trying to establish its own gravitas. It’s sophisticated, but it isn’t lofty. And, no, there isn’t a message. It’s just music for its own, joyful, life-affirming sake. Making it was, she says, fairly easy. “I had problems with my voice, though, because I was so pregnant. I would run out of breath, and my voice isn’t super-strong. I can hear it on the album, every time I can’t quite get that note, or I’m breathless.”

“Baghdad Ragman” almost didn’t make it on to the final running order. “I had written that after I went back to Iran. I was travelling a lot. One of my husband’s three jobs at that point was working for the American Peace Corps. He was head of the architecture programme, so we were going to villages, to really rural, old Iran, not just Tehran. It was very atmospheric. When I asked to put it on the album, Chuck said, ‘No way – that’s just too far out and left field’. But I liked it. I had to bargain. I had to say, ‘I’ll do this song or that song if you let me do “Baghdad Ragman”. The multicultural songs were not liked. They weren’t marketable and they were not going to be singles.” Alexander encountered the same resistance to the Dostoevsky-inspired “Russian Lady” and, once more, vied for its inclusion. Today, it’s the very inclusion of the ‘multicultural’ songs that elevates the album. Had it comprised only her America-inspired songs, it might have been merely a very decent album. But the presence of “Russian Lady”, “Hotel”, and “Baghdad Ragman” had two benefits; first, they’re exceptional songs and second, by providing contrast, they enhanced the impact of the other songs.

It’s surprising to learn that Alexander, whose singing displays a deft lightness of touch throughout the album, didn’t regard herself as a lead singer. “I’m not,” she insists. “I’m a harmonizer. I like blending with people. I wasn’t used to being lead, even on my own songs, and I didn’t think of myself as having a good voice, just a good harmonic ear. I can hear tons of things on the album that grate at me.”

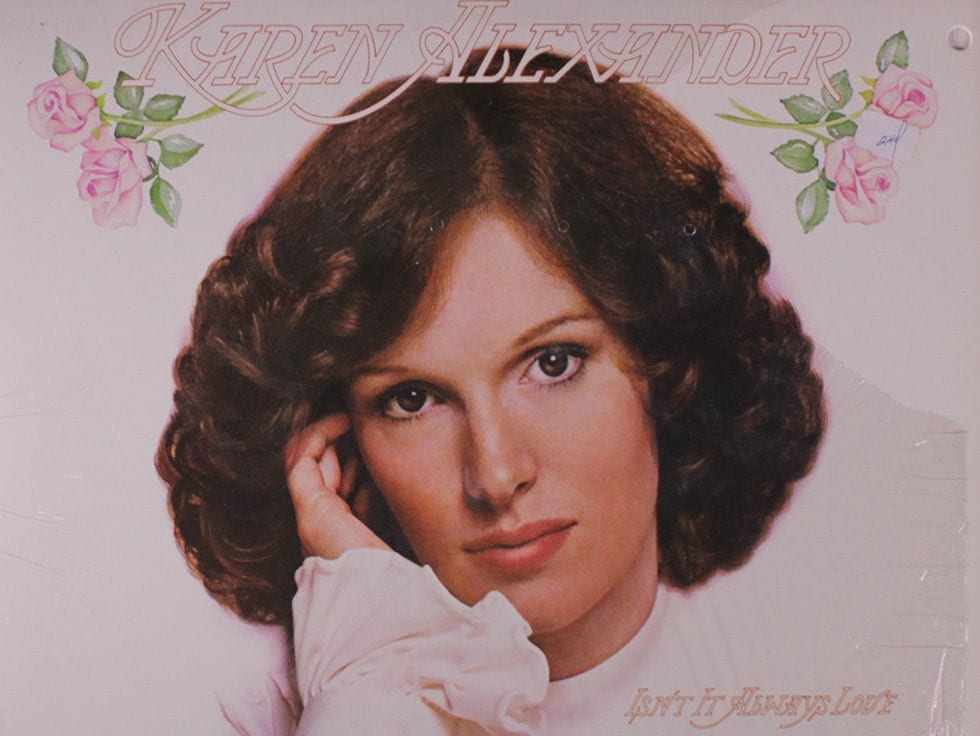

The front cover didn’t sell the album very well. With its white background, floral motif and prim portrait, neither did it endear itself to Alexander. “I wasn’t crazy about it. I didn’t like it at all. My hairstyle was a little prissy – I looked like my grandmother. They gave me three outfits and said, ‘pick one’ and it was a problem because I was so pregnant. And they ended up airbrushing part of my face, so there was a missing piece of jaw and it didn’t actually resemble me. It was a little odd. But I felt that I needed to agree to most things and in the case of the music, I did agree with most things, although it got a little sped up.” On the insert were additional photographs, showing Alexander in her two milieux – the glamorous American woman in evening wear (cropped, to hide the pregnancy) and the Iranian, blending in with her surroundings in tribal dress. On the back cover were the lyrics for “Brown Shoes” and a quaint, Victorian-style illustration of the aforementioned footwear.

Another factor to have an impact on the album’s fortunes was Alexander’s unavailability for promotions and gigs. “It was a difficult situation, having two lives take off in opposite directions. To already have a family and to have two cultures and two ways of life going on. My husband’s life in Iran was taking off in a really nice way. And my life there was nice, too. We had an interesting life that depended on us being there. We didn’t know what was coming, nobody did.” What was coming was, of course, the fall of the Shah, the 1979 revolution and the eventual return to America of most expat families. But before that came Alexander’s second and final album, Voyager (1978). Voyager attempts to upholster her songs with rock instrumentation. In place of David Campbell’s orchestrations, which were sympathetic to Alexander’s songs, delicate and ornamental, Pete Robinson’s are much soupier, like overcooked movie-soundtrack orchestrations. There’s an everything-and-the-kitchen-sink approach to the arrangements, as if the musicians wanted to show off their talents to their fullest rather than think ‘What do these songs need?’.

Voyager is not without its pleasures and Alexander follows her muse to interesting places, with longer songs that explore unusual psychological scenarios. But the joie de vivre is no longer there. “I didn’t like those songs. And it was a labor-intensive, miserable experience. It was harder. My husband couldn’t come because of work. It was tougher, and I wasn’t a very good match with the producer.” The producer was Bob Morin, who didn’t have the same kind of singer/songwriter-friendly CV as Plotkin.

Some of Alexander’s songs had notable after-lives through other people’s voices. Twiggy, who’d transitioned from modeling to entertainment, recorded “Fish in the Sea” and “Brown Shoes” for her 1977 Mercury Records album, Please Get My Name Right. West End and TV star, Julie Covington, recorded “A Little Bit More” for her self-titled 1978 album on Virgin Records. Alexander has no idea how either artist came to know her songs, whether through the efforts of a publishing company or from hearing her album. Twiggy had a pronounced fondness for country, folk, and Americana and also interpreted songs by Wendy Waldman and Joy Of Cooking’s Toni Brown. Please Get My Name Right reached the UK Top 40, so Alexander’s talents did yield some chart action.

Alexander and her family were back in America by the ’80s. She and her husband eventually settled in California, where they spent the next 30 years. “He died about eight years ago. We had moved to Berkeley when he got sick and there’s a jazz school there that’s open to whoever, so I took piano classes. I started writing songs again and they were a little more jazzy, and that’s my interest. I like jazz. When he died, for a year or two I wrote songs that were super-sad, grief-ridden, but not bad. And then, about a year and a half ago, I got married again and now I live in LA. I’m going to be be writing more songs and when I have ten songs that I really like, I’m going to be put them together, a pure vanity project. But I’m also painting almost every day,” she says. “It’s something I’ve wanted to do for a long time. I only have so much energy. I’m fairly new at it, but it’s going the way the music went; I’m surprised I can do it and so are other people, so I’m going to keep on going.”

Isn’t It Always Love is available on Warner Japan Compact Disc.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)