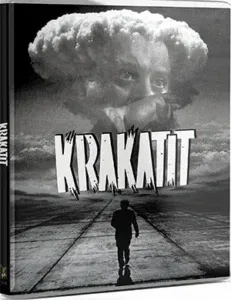

The rediscovery of bizarre science fiction cinema from the archives of Eastern Europe continues apace with Otakar Vávra’s Krakatit (1948). This story is best described as a nervous breakdown of the postwar atomic era and the dawn of the Cold War.

The extraordinary opening shot of Krakatit, as filmed in beautiful high-contrast black-and-white by Václav Hanuš, offers a window on a foggy night, a spidery tree of bare limbs, and distant city lights. As the camera dollies inexorably back, on the left, a doctor in white garments takes a cigarette break, peering pensively outside as his curling smoke drifts into the fog. From the right, a nurse now enters the frame, seen from behind, and calls to the doctor.

The dolly backward cuts to a dolly forward, with slight fisheye distortion, as the doctor and nurse enter an operating room and approach what looks, at first, like a pregnant woman. When we get closer, however, we see it’s a man lying on his side, draped in a sheet. The nurse says the poor, unknown fellow was found naked in the street. The doctor notes meningitis, lumbago, and scarred or burned hands on his feverish, delirious patient. The man is given oxygen, and as he regains consciousness, he begins the jumbled, fragmentary flashbacks, memories, and fantasies that structure Krakatit.

We’d been warned: the first information given to the viewer after the credits is the statement, “The story takes place in the midst of a feverish dream.” Having duly notified his viewers of this license to do as he likes, Vávra will spend the rest of Krakatit doing as he likes, as aided and abetted by a crack production team. Forget following a coherent story. Vávra and his co-writer, his brother Jaroslav Vávra, devise the scenario as a suite of contradictory, sometimes impossible sections, linked only by recurrent shots of the patient dreaming under his oxygen mask.

The first reasonably coherent flashback, or delusion, finds our patient wandering (fully clothed) along a cobbled sidewalk by a river at night, with a train crossing a bridge in the background. A close examination of that train and bridge reveals that we’re seeing models in a studio set, but it’s quite atmospheric. Our man shambles by a few strangers who avoid him, and finally, one tall, thin man approaches and recognizes him as a chemist named Prokop (Karel Höger).

The tall man identifies himself as an old college chum, Tomes (Miroslav Homola). Prokop is irascible and incoherent in his mood swings until he faints. Tomes takes him to his own home and, as it seems to the delirious Prokop, tries to pump him about his invention of a universal explosive powder he calls Krakatit, after the volcano Krakatoa. When Prokop rises from his stupor, Tomesis is gone. A mystery woman (Vlasta Fabianová), whose movie-star glamour is apparent even beneath her veil, appears at the door to entrust Prokop with delivering a letter to Tomes before vanishing just as quickly.

The plotline of Krakatit isn’t as important as the fact that there’s no real plotline at all, only a series of increasingly surreal events that don’t connect except as in a dream. Also, as in a dream, the viewer feels that developments are on the verge of making sense in the next few minutes. What’s consistent is that Prokop is haunted by the destructive power of his invention and that various forces want it. A double-talking foreign agent in loud ties, Carson (Eduard Linkers), does most of the bullying.

After an idyllic rural interlude from which he’s abruptly jarred by the next transition, Prokop spends a long stretch of time as a prisoner in a castle of decaying foreign aristocrats from toppled regimes. There, he finds himself drawn to the imperious ice-beauty of square-shouldered Princess Wilhelminia, whose willingness to manipulate him includes secret sexual encounters.

She looks so much like a statue that in one scene she literally becomes one. Cultists and sci-fi film buffs will recognize Florence Marly with delight, famous as the titular vampiric alien in Curtis Harrington’s Queen of Blood (1966).

While Marly was born in Czechoslovakia, Krakatit is the only film she made in her native country. She’d been most active in France before the war, where she married a very interesting director, Pierre Chenal, and worked with him several times. During the war, they fled to Argentina (he was Jewish) and worked in the film industry. While Krakatit marked Marly’s postwar return to Czechoslovakia, she soon left for Hollywood, where her career was checkered and frustrated, if intriguing.

Krakatit’s politics lie in its anguished cry for peace and humanitarianism, which has to do with rejecting elites and fascists as consistent with the country’s new line after the Communist takeover a few weeks before the film’s release. The screenplay tends to lean heavily on blaming poisonous foreign influences associated with a Mephistopheles figure named D’Hemon (Jiří Plachý), and everyone knew which country possessed atomic bombs. Prokop’s scarred or burned hands mark his sense of guilt, as with Lady Macbeth.

So much of Krakatit is visually show-offy that we’re convinced Vávra must have been familiar with Orson Welles’ films. Certain shots, such as entering a room or traveling beneath a horse-drawn carriage, show Wellesian delight in the plastic nature of cinema. Vávra is obviously familiar with Expressionism’s distortions and its heavy use of shadows. The notion of an unbalanced mind unreeling a story before our eyes harks back at least as far as Robert Wiene’s The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920).

Just for fun, composer Jiří Srnka sometimes throws in what sounds like a theremin. We also have a ravishing montage of a nightclub band with a hep cimbalom player and a gyrating female dancer in a skimpy dress.

What’s especially strange is that Krakatit is also described as a reasonably faithful filming of a 1924 novel of the same title by Czech science fiction writer, satirist, and philosopher Karel Čapek. As explained in the liner notes by teacher and researcher Jonathan Owen, and in the commentary by Czech film expert Irena Kovarova and film historian Peter Hames, the framing device of a nameless ill patient has been borrowed from another Čapek novel, Meteor (Povětroň, 1935), but much of the other material emanates from the similarly dreamlike and experimental 1924 novel.

As Hames observes, what had been a warning in the novel has evolved into contemporary commentary in the film. What’s unfortunate is that, even shorn of the specific politics of its 1948 moment, Krakatit still resonates with its message of neurotic hysteria in the face of technology and fascism. The “all a dream” structure and the open use of fantasy don’t nullify the apocalyptic sobriety of events.

Krakatit is the second 1940s science fiction movie from Eastern Europe released by Deaf Crocodile within a few months, the previous being Dezsõ Ákos Hamza’s Sirius. The gorgeously rich digital restoration is presented in a dual Blu-ray/4K UHD combo pack currently available in a limited edition of 1,750 copies with slipcover and booklet. The Deaf Crocodile site promises a standard edition “at a later date.”