Tenor saxophonist Melissa Aldana is from Santiago, Chile, where she grew up as the daughter of a professional saxophone player. She started playing at age six, met the Panamanian jazz pianist Danilo Perez when she was 18, and later studied at Berklee College of Music. It almost seems like a jazz fairy tale: she was in New York City studying with the legendary George Coleman in 2009 and was the first woman to win the Thelonious Monk Jazz Competition for saxophone in 2013. She was 26.

The pressure on Aldana must have been serious, but her response has been to work hard, challenge herself by playing with superb musicians, and measure her own playing against the best: heroes such as Sonny Rollins and Wayne Shorter.

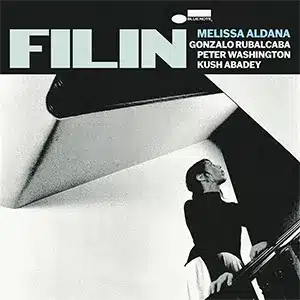

Her new album, Filin, is her first set of ballads — a career challenge of the first order. In addition, six of the eight songs are from Cuba and were written in the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s, in the romantic “filin” tradition. The concept was developed, arranged, and now recorded with Cuban jazz pianist Gonzalo Rubalcaba, a quarter-century older than Aldana. The tunes, largely unknown to American ears, have the melodic and harmonic richness of tunes from the Great American Songbook, but their poetic lyrics are in Spanish, Aldana’s native language.

The record is elegant and refined but not superficial or excessively “pretty”. Melissa Aldana is accompanied simply by Rubalcaba’s piano, bassist Peter Washington, and drummer Kush Abadey, with singer Cecile McLoran Salvant adding delicious vocals on two tracks. Tempos are moderate throughout; every note is exposed. Feelings are on the surface but expressed with subtlety.

From its first notes, Filin is enchantment. Rubalcaba plays a spare solo introduction to “La Sentencia” before Aldana joins him to state the melody with gauzy grace. Neither plays a note beyond the essential. The band enter with a rising figure that surges in ideal coordination, after which we are in the land of gorgeous jazz ballad playing. Abadey whispers with brushes on his snare and hi-hat; Washington could be Percy Heath in the 1950s, choosing perfect notes; and Rubalcaba is very nearly a harp in the delicacy of his accompaniment.

Aldana restates the melody and embellishes it, but her improvisation remains close to home: comforting and warm. She sounds every bit like a singer. When the band add McLoran Salvant as a singer, the balance is perfectly struck. McLoran Salvant’s vocals are ideally modulated to the material: unshowy but able to alter her tone and phrasing to bring emotion with sophistication.

In “No Te Empeñes Más” (“Don’t Insist Anymore”), she is clear and plain-spoken, accompanied only by Rubalcaba, and adds traces of sharpness and vibrato as the bass and drums slide beneath her. The form ends with two short descending phrases that she sings along with the group, followed by the word “adios”. Melissa Aldana improvises for just eight bars, using her rich low register, a silky baritone Stan Getz you might say, giving way to Rubalcaba for eight, sending us back to the song’s bridge. When McLoran returns to “adios” for the end of the song, she repeats it three times, each different but in her upper register.

The singer is also featured on “Los Rosas No Hablan” (“The Roses Don’t Speak”), a Brazilian song. Another short saxophone solo follows her vocal, this time in Aldana’s gentle middle register, where she bends notes into each other and plays flickering downward runs, then traces soft obligato phrases behind the vocals. She complements McLoran Salvant almost like a great bass player, running beneath her but often finding notes that veer across with harmony with subtle surprise.

Perhaps the most important element of Filin is how it dares Melissa Aldana to embrace a truly personal sound. Her early recordings, understandably, found her in the shadow of some of her heroes — a situation that the young player didn’t shy away from. Her 2024 album, Echoes of the Inner Prophet, was truly outstanding, but the title track was dedicated to Wayne Shorter, an indication of his shadow over the whole project. Her playing was not that of a Shorter clone, but the new recording seems even freer of any one influence.

In the Hermeto Pascoal song “My Church”, she etches the melody in her whispered upper register, using rippling runs that sound like Shorter, bending notes, and a hand technique to flutter notes — elements that don’t come from Wayne. She steps back to let Rubalcaba play a delicately staccato solo and, when she returns, it is with a breathtaking run that combines slurred/bent notes, clear articulation, changes in melodic direction, and modern harmonic ambiguity. She is not tracing the song’s chords with scales or arpeggios but carving out a fresh melodic line with its own logic and beauty. She sounds like no one else.

Filin isn’t a virtuoso showcase for pianist Gonzalo Rubalcaba, but he hardly needs one. His presence throughout is one of ideal support and taste. His block-chord introduction to “Ocaso”, for example, gives the band a chance to shine, and his comping for Melissa Aldana is minimal, full of small filigree and melodic call-and-response. This performance also features bassist Peter Washington, who qualifies as the most tasteful bassist in the world after decades of playing in trios led by Tommy Flanagan and, more recently, Bill Charlap. His playing here strengthens that case.

Perhaps the sharpest overall performance on the album is the closing track, “No Pidas Imposibles”. The ballads across the whole album don’t often feature the polyrhythms we associate with Cuba and Brazil. Here, however, Abadey builds a quiet Cuban groove into his snare/brushes playing, and Washington finds the idiomatically correct bass patterns. The result is a bit more rhythmic from Rubalcaba and Aldana. The out chorus played by the pianist at the conclusion of Filin is pure joy.

At only 39 minutes, Melissa Alada’s new album brings to mind some of the classic LPs from jazz’s history — John Coltrane’s Ballads or Portraits in Jazz by the Bill Evans Trio. Each performance is relatively brief, with soloists rarely taking more than a partial chorus for their improvisation. The overall sensation is not just beauty (though, yes, it is a gorgeous album) but distillation. The songs, even those without sung lyrics, get definitive interpretations. For all its purposeful restraint, Filin does not make you wish that these great musicians would cut loose. Rather, it seems perfect as it is.