Imagine a shelf of classic toys and books. There might be a teddy bear, Barbie, G.I. Joe, a Mouse Trap board game, Star Wars figures, and Mr. Potato Head, along with books like Curious George, Frog and Toad, The Snowy Day, Where the Wild Things Are, and Harold and the Purple Crayon. Comic books would also be included, like the classic Spider-Man, Superman, and Batman. If there’s something these toys and books have in common, it’s that they’ve more or less remained popular through the decades and have defined the American childhood.

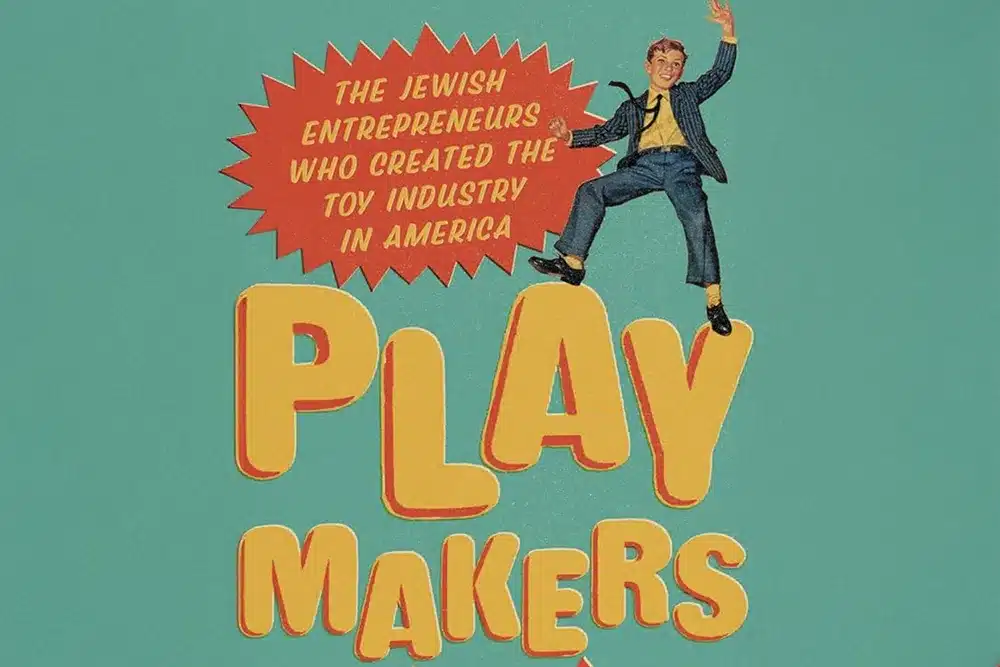

There’s something else these toys and books have in common. They were all developed by Russian and Eastern European Jews. As Michael Kimmel writes in his new book, Playmakers: The Jewish Entrepreneurs Who Created the Toy Industry in America, these toys and books came into being because their creators were shut out of the American workplace.

Kimmel has made his career writing about masculinity in America, and Playmakers touches on that, too, but this story is especially close to him because his relatives—going back generations—were central to the toy industry when they founded the Ideal Toy Company. Like many Russian Jewish immigrants, Kimmel’s relative Morris Michtom and his wife Rose settled in Brooklyn—along with one million other Jews, making it the largest Jewish city in the world at the time—and opened a small candy shop.

They also created the teddy bear after President Teddy Roosevelt refused to shoot a bear on a hunting trip, winning the hearts of many Americans, including Morris and Rose. The Michtoms displayed their stuffed bear in the window of their shop, and when passersby spotted it, they asked to buy it. Soon, they had more orders than they could handle, and Ideal Toy Company was born.

Other major toy companies, like Hasbro and Mattel, were also founded by Jews of Russian and Eastern European backgrounds. Because borders often shifted and a place like Vilna could be Polish, Russian, or Lithuanian depending on the year, Kimmel uses the term Yiddish Jews for more accuracy than Russian or Eastern European Jew. Yiddish Jews who arrived at Ellis Island around the turn of the last century differed in language, culture, and socioeconomic background from the German Jews who had settled in the United States a good half-century earlier.

Kimmel also shows how German Jews were involved in the toy industry. Many of the big department stores—think Macy’s and Gimbels—were started by German Jews. One of the more eye-opening parts of Playmaker‘s research occurred when Kimmel wrote about the phenomenon of the Christmas season. It’s now common knowledge that Jews wrote many of the secular Christmas songs like “White Christmas”, “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer”, and “I’ll Be Home for Christmas”, to just name a few. German Jews played a larger role in how Christmas came to be celebrated in America.

As Kimmel writes, “These stores invented the Christmas ‘season,’ heralded by the appearance of Santa Claus at the end of every Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade since the event’s founding in 1924. Christmas was becoming quite profitable, leading to conservative calls to ‘Keep Christ in Christmas,’ which might just as well have said, ‘And Keep the Jews Out’ in parentheses.” None of these department store promotions would have been possible without the toy industry being ready to fill stores with the latest dolls or board games.

Kimmel also shows how gay Jewish authors like Maurice Sendak and Arnold Lobel found acceptance in children’s book publishing during a time when it was neither physically nor professionally safe to be out. In a similar fashion, the earliest comic book writers were predominantly Jewish and developed the medium after being shut out of professional positions.

As Kimmel writes, “The world of comic strips, the entire world of superheroes, was a virtual Jewish ghetto—a ghetto created in large part because a slew of young Jewish artists had been frozen out of the higher sorts of artistic endeavors, architecture and advertising. Necessity born of anti-Semitism, talent, and no small amount of moxie—er, chutzpah—combined to usher in what is now considered the ‘golden age’ of comics.”

It may seem like Jewish toymakers, children’s authors, and comic book writers and illustrators took risks when other groups preferred sure-bet routes to earning a living, but Kimmel writes that the opposite was true. Instead, it was “that conservative desire to fit in, to not upset the American applecart: this is the Jew’s ultimate wish. To be accepted as no different from anyone else. To fit in, to not stand out. Unlike other religions, Jews don’t proselytize. Alone among the monotheistic faiths, they have no need to convert you. They just want to be left alone. When you stand out, you are isolated, frightened, and vulnerable to attack. When you fit in, no one sees you.”

The subtitle, The Jewish Entrepreneurs Who Created the Toy Industry in America, is a little misleading because Kimmel’s book is more of a narrative of 20th-century American childhood, including the ways in which toys—but also children’s literature and comic books—played a central role in making children heard, not just seen.

One question Kimmel leaves open is: What happens next? With electronic devices and social media taking over American childhood so early into this new century, will there still be a market for dolls, action figures, and board games? What about children’s books and comics? Toys, children’s books, and comics expand children’s imaginations and foster creativity. Can the same be said of endless hours of YouTube videos on the iPad? Is childhood as we knew it a thing of the past?