Klinger: I was just a babe in arms as it was happening, but it seems safe to say that as the 1960s turned into the 1970s, rock critics on the whole got to be more than a little bummed out. Their hippie dream hadn’t quite panned out. The old guard bands were either breaking up, keeling over or seemingly starting to fizzle. Even their beloved drugs seemed to have a hidden dark side. This could explain why they had such a grumbly attitude about the up-and-coming bands that were springing up at the dawn of the decade.

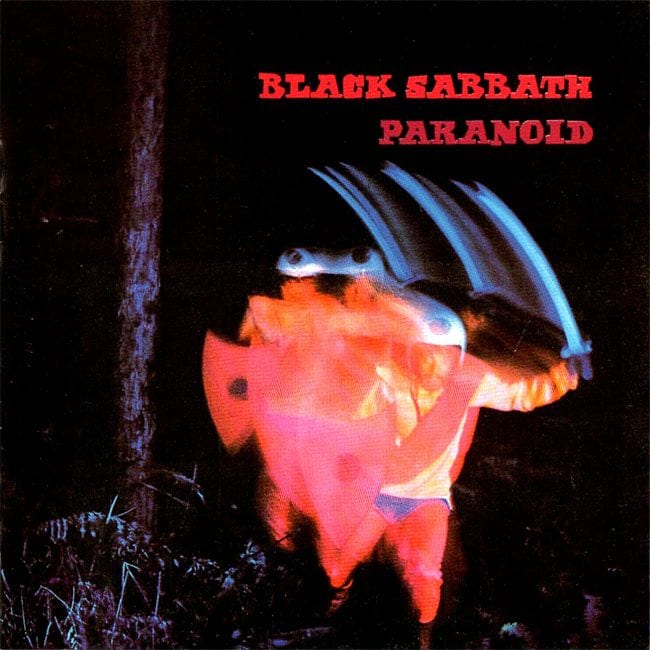

We’ve discussed how Led Zeppelin took their lumps among critics, and now the Great List has given us another group who seem to have taken years to see a rehabilitation of their image, Black Sabbath. And all I can say is thank God that has happened, because let me state for the record: I love Paranoid. Unequivocally and unabashedly, without qualification or clarification. My previous experience with Black Sabbath had sadly only skimmed the surface, so I thank the Great List for making me dive in and pay attention to this album.

Mendelsohn: Growing up a teenage metalhead dirt bag, I spent the requisite amount of time listening to Black Sabbath and Ozzy Osbourne’s solo material. I swore all of it off when I cut my hair and traded in my black t-shirts and boots for cargo shorts and Birkenstocks in college. Thankfully, that period in my life was even shorter lived (ha! Phish didn’t even make the Great List). I lost any remaining respect of Ozzy once he decided to let America into his living room and we all learned that rich people like dogs and don’t seem to have a problem with them pooping on the floor.

Listening to Paranoid again after so many years was like a trip back to simpler times. I don’t quite have the unabashed love for Sabbath that you do but I was amazed at the musicianship of the band, especially Geezer Butler’s bass work and the drums of Bill Ward. I hadn’t expected to find Ozzy voice to be so grating and flat. But maybe that’s just left over prejudice from his insipid reality show.

And as you rightly noted, time has been kind to this band. Dismissed early on, Black Sabbath paved the way for several distinct veins of rock ‘n’ roll and has only seen their legacy grow as new generations of rockers discover their music. This is one of those albums that I wouldn’t have been surprised to have seen in the Top 100 but even now, I find myself wondering why it took us so long to get to it.

Klinger: I don’t know too much about the algorithms and methodologies and whatnot, but I’d say that’s mostly down to the idea that Black Sabbath got terrible reviews at first. Even the legendary Lester Bangs, who I would have thought could really get into Sabbath, said that they were, “like Cream, but worse.” Also apparently he didn’t like Cream. Interestingly their star ratings in consecutive editions of The Rolling Stone Record Guide tell an interesting story. 1979/1983: One star. 1992: Three and a half stars. 2004: Five stars.

But none of the early critical drubbery makes much sense to me. Iommi, Ward, and Butler were, as you said, an insanely tight power trio—I really can’t get enough of Geezer Butler’s bass work, which manages to be both melodic and punchy. But what I find most striking about the songs on Paranoid is that Black Sabbath didn’t write songs so much as they wrote suites. They really weren’t bound by the ideas of verse/chorus/verse, and their songs are the more interesting for it. That part about three minutes into “Iron Man”, where they’ve been lumbering along for a while and all of a sudden the song shifts into overdrive and whips you around by the scruff of your neck and then settles right back down into the lumbrage? Gets me every time. (One of the most conventional tracks on the album, “Paranoid”, was whipped up in about 20 minutes when they found they had space to fill. Think of that…)

Mendelsohn: I don’t understand the poor reviews either. Black Sabbath was effectively doing something completely different with rock music in a way that should have captured the critics attention, not raised their ire. It may have something to do with the unfiltered anger that shows its teeth in several sections of this record. But even then, they weren’t really saying anything all that different—be it the anti-war message of “War Pigs” or the sci-fi oddity of “Iron Man”. The word satanic did get tossed around quite a bit in reference to this record and Sabbath in general, but there is little to support that notion aside from the hellish guitar licks coming from Iommi.

The two things that I have always loved about this record are “Planet Caravan” and “Rat Salad”. The former is a fantastic detour through stoner psychedelica that toes the line between rock ‘n’ roll and some rather avant-garde jazz guitar work from Iommi. The latter really shows off the chops of the power trio at the center of Black Sabbath. Without Ozzy’s wailing, Butler, Ward, and Iommi set off on a short-lived burner that would put any rock band to shame. Again—no Ozzy. On second thought, I could see why certain elements of this record would have annoyed the critics.

Klinger: Well, where you hear flat and annoying, I hear a distinct break from the quasi-soul stylings of the previous generation of singers. I’m kind of enjoying the idea that Osbourne wasn’t wailing away like, say, Robert Plant. I think it grounds the proceedings quite nicely and lets the real excitement of the band—their unerring sense of groove—take center stage.

Whatever the nonsense that has been brewing between Bill Ward and the rest of the group, the fact remains that it’s his groove that makes Paranoid so distinctive. No matter how much people want to see Sabbath as nothing more than a proto-metal band, their real roots lie in the heavy blues scene of late-’60s Britain. Again, not to pick on the critics (ah, who cares?), but for some reason they kept harping on the idea that Black Sabbath didn’t swing. Which is absurd. Ward’s obvious jazz influence comes through all throughout the album. Then again, they said the same lack of groove with Led Zeppelin, so maybe there was something in the electric Kool-Aid back then.

Mendelsohn: I don’t want necessarily want Ozzy to be Robert Plant—that would definitely overshadow the groove. And as you rightly pointed out, it is the groove at the center of Black Sabbath that makes for such an appealing album. While Ward, Butler, and Iommi are all strong players, they are really more a sum of their parts, then say, a band like Led Zeppelin or Cream. I just want a little more from Ozzy. He doesn’t have to wail but he could be just a little more dynamic in approaching his vocal duties—and singing through a metal fan doesn’t count. You really don’t get any real movement in his vocal range until the end of the album, most notably “Fairies Wear Boots”. And I’m using the word “range” as loosely as possible in this case. Ozzy doesn’t have to be a virtuoso but it wouldn’t hurt if he didn’t sound like some untrained street tough shouting into a microphone.

Honestly, though, I’m just nitpicking at an excellent album. It’s not like I’m making some outrageous compliant about Black Sabbath’s inability to swing. Really? Swing? I could understand if the critics didn’t like it because it was too heavy, or lacked the pop luster, but dinging an album because it didn’t swing sounds a little old-fashioned.

Klinger: Yeah, I never really understood that either. It seems like a pretty abstract concept, like those wine dorks who jabber on about whether something tastes enough like oak. Ultimately, I think a lot of folks back then were freaked about with Black Sabbath because they seemed to be fully embracing the dark stuff. It’s only recently that people have noticed that their lyrics are way less nihilistic than they initially may have seemed, and in fact all those references to war and drugs and Satan and whatnot were meant to be cautionary tales from a guy who had seen that stuff and the damage done.

Of course, that dark stuff extended even beyond the lyrics. That deep sense of foreboding came about in the music, and a lot of that comes from Iommi down-tuning his guitar– a necessity, following welding accident in his youth — that became a signature part of their sound. Ultimately, though, all the kvetching about the accoutrements surrounding Black Sabbath just misses the point. They were clearly a good bit smarter than people wanted to give them credit for. In that sense, it isn’t surprising that the criterati eventually came around. But it is heartening.

(By the way, readers keeping track may have noticed that the Great List has been updated. Big excitement and lots of fun for the listophiles among you! We will be addressing the albums that snuck in above No. 135 in upcoming editions of Counterbalance, and we’ll do our best to make your transition through this topsy-turvy time as smooth as possible. In the meantime, go sift through all the ups and downs and we’ll talk again soon.)

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)