Pink Fender by rahu (Pixabay License / Pixabay)

Genre analysis is an inexact methodology. Art rarely conforms fully within the parameters of what has been defined as a genre. And even when it does, it rarely incorporates all of those features within the shared traditions that have prompted the genre generalization. Punk rock is such a case, its artists and art invariably transcending the genre’s expectations; but so is rock music in general, and any other form of art. Like punk, rock ‘n’ roll existed in mutated manifestations long before that designated genus was even in common usage. Thus, garage punk and psychobilly, two examples of hybrid punk, are rooted in forms and styles that precede punk’s 1976 break-out year, just as rhythm and blues and jump blues displayed many of rock ‘n’ roll’s key characteristics prior to 1955.

Still, genres are useful: for categorical marketing by the music industry and media, and for the tribal affiliations of fans. They are also useful—and essential—for this study in order to understand the manifestations of the punk aesthetic: where it has come from, where it has been, and where it is going.

What it is exactly will always be contested, but only by recognizing punk as a phenomenon of commonly held traits can we appreciate its elasticity and ability to morph into new shapes. Punk rock may be a Rorschach test, but it still harbors recurring features, many of which exist beyond musical criteria.

Whether regarded as a rock form, style, subculture, or attitude, punk has displayed a spirit of innovation and exploration that has never allowed it to sit still. Since its earliest musical demonstrations to its most recent, punk rock has operated as a hybrid genre, transforming other rock genres while also being transformed by them. In mixing with others, punk has renovated into new genre-busting forms, keeping the spirit alive and kicking even when transforming into barely recognizable mutations.

So, is a study of cross-overs vulnerable to subjective characterizations? Yes. Have such categorizations become redundant now that

all genres are mixing and matching? Probably. Yet, to assess the journey of punk one has to first accept that it exists, and that it displays a sufficient number of shared traits for us to come to a consensus—if not unanimity—on that existence.

Few rock genres have resisted the lure to be subsumed into a punk hybrid, though some have been more amenable to fusion than others, each forming and flourishing to differing degrees at different times in their histories. In 1976-77, punk evolved into a recognizable state by rejecting many of the genres of its time. Indeed, its very impetus and distinction came from presenting an opposition front to the power-house forms of the ’70s: progressive rock, soft rock, and disco. To fuse with these genres would have been to betray the very core tenets of punk’s antagonistic identity: amateurism, aggression, and anti-establishment attitudes. Nevertheless, 1976 punk was not as pure or autonomous as it has sometimes been portrayed, with many of its key players openly synthesizing their bare-boned rock ‘n’ roll riffs with sounds emanating from garage, glam, and reggae outposts.

Hybrids abounded around 1979-80, by which time primary punk had found itself in a creative cul-de-sac. And like so many art forms in the midst of this emerging era of postmodernism, punk revitalized itself by reaching out and blending with other genres; some, like disco, funk, and prog rock, it had disavowed just a year or two earlier. This period of post-punk, new wave, and new pop produced a myriad of intriguing punk mash-ups, with funk, reggae, and rockabilly proving particularly willing marital partners. Al Spicer characterizes 1980 as the year when there were “plenty of busy bunnies…morphing punk into a whole new bag of odd plasticine shapes” (p.45).

By the mid-’80s punks and ex-punks were scouring rock history for new relatable partners, leading to all kinds of curious relationships. Rap, jazz, pop, folk, country, and heavy metal were all tapped for fusions that prevail to this day. Hybrids are not unique to punk rock, yet few forms have been as malleable for as long.

Garage Punk

Testament to the fact that a genre can exist without yet being recognized as such, early ’60s garage punk displayed energies, attitudes, and musical traits we would later come to associate with punk proper. Garage punk might thus be regarded as a retrospective punk hybrid.

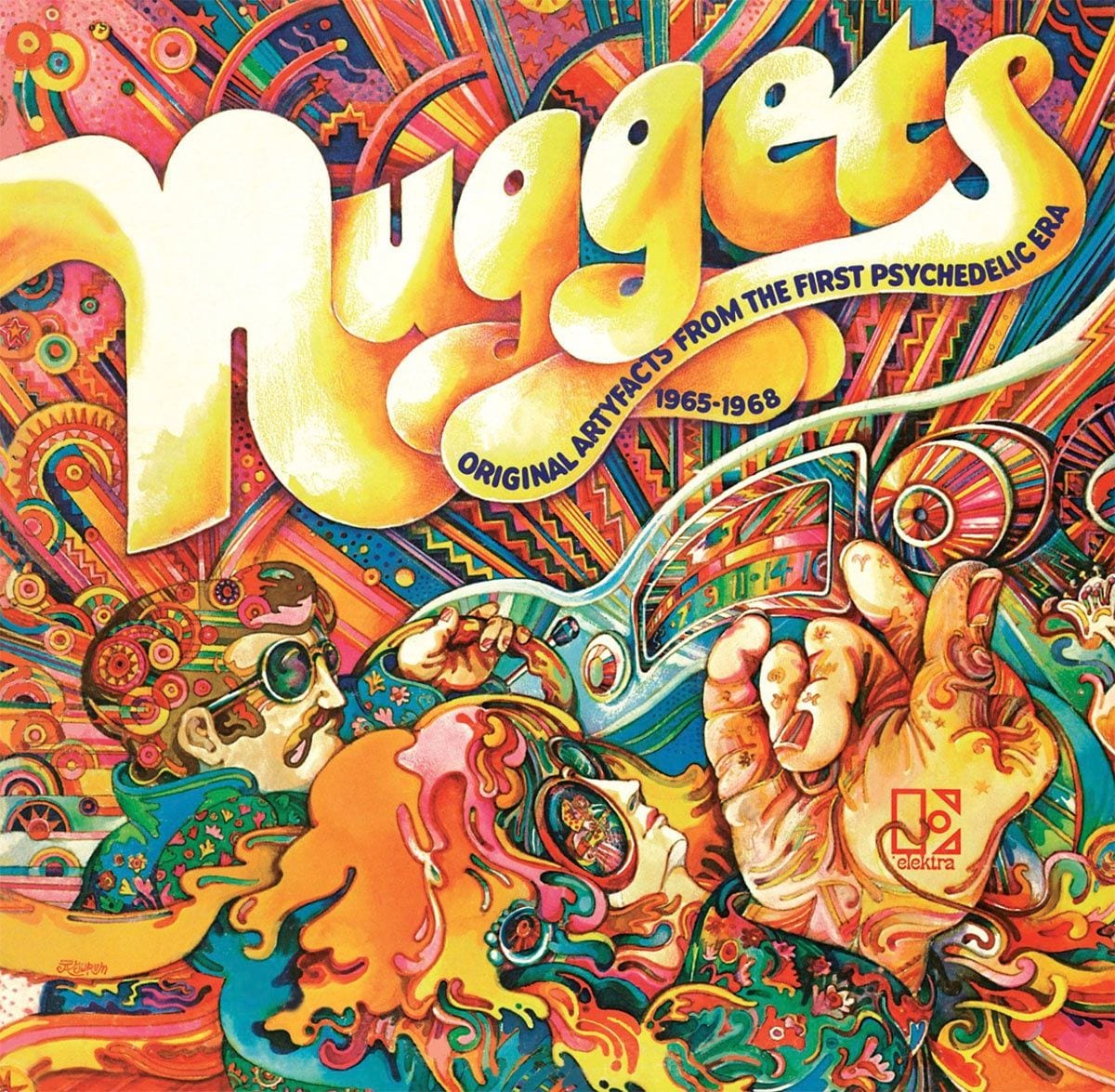

It has proven to have legs, too, undergoing periodic revivals over the last 50-plus years on both sides of the Atlantic and beyond. Terms such as garage, frat, and surf rock were often used to describe these bands in the early-to-mid ’60s, but the moniker of “punk” only become common after Electra released a two-disc compilation of songs in 1972 that Lenny Kaye had organized under the title, Nuggets: Original Artyfacts From the First Psychedelic Era, 1965-1968 (Elektra, 1972). His reference in the sleeve notes to some of the contents as “punk rock” ushered the term into the critical lexicon, where it has been variously applied ever since.

Kaye’s involvement with garage punk is more than a footnote, though, as just a couple of years later he went on to become lead guitarist for the Patti Smith Group, one of the leading lights of CBGB’s proto-punk. That band famously forged attachment to their garage roots by opening their debut album, Horses (1975), with a raucous rendition of “Gloria”, the garage staple first recorded by Van Morrison’s Them in 1964. Patti Smith’s more express(ive)ly punk-oriented version signaled—as Nuggets did—both a recognition and a passing of the torch of garage as it got sucked into the burgeoning punk maelstrom.

An ardent fan and celebrant of the proto-punk sounds of The Velvet Underground, Stooges, MC5, and New York Dolls, as well as of pre-proto-punk ’60s garage, Kaye serves as a significant taste-maker and representative fan of punk rock’s main historic highway.

Nuggets has proven to be an important prompt, too, beyond its 1972 release year, with re-releases in 1976, 1998, and 2006 coinciding with groundswells of garage punk rock.

Some garage bands had ambitions for success but merely lacked the resources and equipment to progress into the mainstream. As their site descriptor suggests, these bands usually practiced in their parents’ garage and many never sought to venture too far beyond. But in the garage, as the Clash, the Members, and Weezer have since celebrated in their respective odes, “Garageland” (1977), “The Sound of the Suburbs” (1979), and “In the Garage” (1994), carefree amateurism is given free reign and a raw cavernous sound is inevitable. This “garage” sound can be heard on the original ’60s records, in productions where the sounds are less muted, less restrained, and more reverb-drenched than on the beat hits of the day. The Monks’ “I Hate You” (1966) is an illustrative example, with its unhinged shrill vocals fighting for survival over the bare-boned distorted dirge of riffage and pounding laid down behind it.

Before The Beatles et al invaded, conquered, and colonized, garage rockers existed in the US, though they often incorporated different sonic elements such as a howling saxophone, a hangover instrument from late ’50s frat rock, or speedy guitar note patterns inspired by the surf sounds of yesteryear. These mutations are the older siblings of garage punk, and their legacy, established by the likes of the Sonics and Link Wray, can be heard in subsequent punk potions concocted by the Birthday Party, Agent Orange, and Rocket From the Crypt.

In its pervasive attitudes of youthful anger, angst, and frustration, garage foreshadows punk’s personality, too. However, whereas later punk applied its energies to the social and cultural conditions of young people, garage’s complaints were mostly about “girls”, eliciting a strain of sexist aggression that was often frowned upon when applied with less restraint a decade later by the likes of the Stranglers and Fear.

Comparisons abound in relation to music, too. Three chords, three minutes max songs, built around the basic tenets of rock ‘n’ roll are fundamental to both garage and punk. This back-to-basics philosophy brought with it raw sounds and lo-fi production that reflected a DIY spirit. Recognizing that their fate was likely to be obscurity, garage punks adopted a nothing-to-lose attitude in pursuing outrageous sounds, perhaps playing a more fuzzed-up guitar than the Kinks’ Dave Davies or a more gut-busting scream than the Who’s Roger Daltry unleashed. The resulting in-your-face blasts of punk vitality are on full display in the sounds of the Sonics, the Seeds, ? and the Mysterians, and the Music Machine.

Despite largely writing on teen themes of making up and breaking up, garage punk still managed to ruffle feathers, if not quite to the same degree that later shockers like the Sex Pistols and Dead Kennedys would. In 1958, Link Wray caused a stir by sound alone, if not by title, with “Rumble”, a surf burner featuring the kinds of power chords, distortion, and feedback that would become ubiquitous features of punk guitar post-1976. Even though it was an instrumental, the song was still banned on US radio for fears that it might provoke public disturbances.

The Kingsmen’s “Louie Louie” (1963) was equally controversial, its slurred, inarticulate singing eliciting the attention not only of soon-to-be-punks, but the FBI, too. The latter’s investigation into whether those drunken vocals were uttering obscenities came up empty; however, the Bureau’s crack team of listeners clearly missed the part where the drummer shouts “fuck” after dropping one of his sticks, a faux pas the band chose to keep in the final mix. Toying with the censors has been a popular prank for garage punks, whether from Roger Daltry stuttering suggestively on the F of the F-word “f-ffffade” in “My Generation” (1964) or Johnny Rotten stretching and separating the syllables of “vayyy-cunt” in “Pretty Vacant” (1977).

The Who, alongside the Kinks and others, provide convincing rebuttals to prevailing assumptions that garage punk was a strictly US phenomenon of only underground acts. Both Brian Ferry and David Bowie helped correct that notion by including songs from a number of British garage bands on their respective “covers” albums, These Foolish Things and Pinups, both released on the cusp of early proto-punk in 1973. Rhino Records also balanced out the American bias shown in the selections for the original Nuggets by releasing a sequel entitled Nuggets II: Original Artyfacts From the British Empire and Beyond, 1964-1969 in 2001.

Perhaps the most intriguing example of the international reach of the garage punk spirit of the mid-’60s is Peru’s Los Saicos, to some ears the first ever full-on punk combo. Like so many of their Anglo-American peers, the band only released a few singles over a brief two-year career, but among them were songs featuring key components of future punk rock: rough production of cheap-sounding instruments; a lead vocalist (Erwin) that foreshadowed Iggy Pop in his capacity to unleash blood-curdling screams between ominous growls on the mic; and a set of stark lyrics that shared grievances both personal and public. “Demolición” (1965) is as shocking as anything released thereafter, its repeated calls for destruction of the train station previewing Johnny Rotten’s similar “destroy” manifesto in “Anarchy in the U.K.” (1976).

To trace the full legacy of garage punk would take a more sizable essay than this, but perhaps the genre’s most notable aspect has been its endurance despite residing in mostly underground habitats. Never a mainstream phenomenon yet never off the radar, garage punk has survived as an aficionados’ music, a player’s music, and—dare I say—music for willful obscurantists and back-to-basics snobs.

Like punk, its unadulterated purity has allowed it to bask in the cool end of the rock pool, while its simple demands have made it amenable to any three-chord punks. Like punk, too, garage pops up periodically to counter rock trends whenever they veer too far towards the slick, serious, or sophisticated. Thus, we saw the arrival of The Stooges and Flamin’ Groovies when prog rock peaked in popularity in the early ’70s; we saw the pub-inspired punk of the Saints, the Vibrators, and the Jam when soft rockers shared stadiums with those proggers; we saw the post-punk of bands like the Fall when post-punk itself got too self-indulgent.

The garage punk hybrid reached its commercial zenith in the mid-00s with the minor success achieved by the so-called “The” bands (White Stripes, Strokes, Hives, Vines), who, along with the the Kills, the Von Bondies, the Libertines, and the Black Lips, carried the form forward in varying degrees of range and rage. Today you will rarely find a college town that does not boast a few of its own (retro) garage punk bands, ready—alongside their in-with-the-in-crowd cult followers—to educate, stimulate, and motivate the unenlightened masses.

* * *

Work Cited

Spicer, Al. A Rough Guide to Punk. Rough Guides. 2006.

- The Soft Pack: The Soft Pack - PopMatters

- Hardcore Punks and Their Shenanigans in the Outhouse - PopMatters

- Wild Night with Yeah Yeah Yeahs at New York Homecoming ...

- The Coathangers: Nosebleed Weekend - PopMatters

- SXSW Music Day 2: Burger Records Burgerstock: White Mystery + ...

- Hunx and His Punx: Street Punk - PopMatters

- The Kinks and Their Bad-Mannered English Decency - PopMatters