Silent films, as we’ve often observed here at PopMatters, are bigger than ever. We live in an age that celebrates their restorations in film festivals, on home video, through streaming services, and even works on the printed page.

While the majority of viewers probably remain apprehensive at the thought of sitting through something old and without spoken dialogue, those who dip an eye into the silent experience tend to find themselves hypnotized and enchanted by their properly restored, carefully curated presentations. Here we have two recent Blu-ray contributions to the revival of our knowledge and appreciation of silent films.

One disc, Italia – Fire and Ashes, is a documentary, or perhaps not quite a documentary, on Italy’s silent film heritage. The film is more of a dreamy meditation on the evanescence of history, memory, and nitrate.

The other Blu-ray, Focus on Louise Brooks, celebrates one of the most recognizable icons of silent cinema. American star Louise Brooks has an instantly recognizable pearlescent gaze and a helmet-like bob whose edges are pointy enough to poke an eye out.

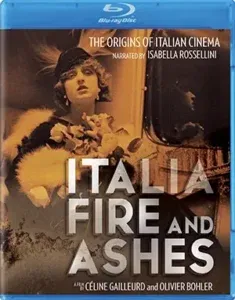

Italia – Fire and Ashes (Kino Lorber)

As put together by Céline Gailleurd and Olivier Bohler, the 90-minute film called Italia – Fire and Ashes (Italia. Il fuoco, la cenere) could be described as a documentary about Italy’s silent cinema, but it’s not as straightforward a delicacy as that implies.

Using nothing but dozens of clips from what remains of Italy’s silent film history, Italia – Fire and Ashes traces several themes and developments chronologically, accompanied by music and historical passages read aloud by actress Isabella Rossellini. The result is a kind of elegy that, because it pays attention to World War I, the rise of Italian colonial fascism and Mussolini, and the rise of cinema, becomes a meditation on mortality, hubris, escapism, propaganda, and the secret powers of narrative imagery to mean more than themselves.

The images are rhapsodically gorgeous and evocative in their tinted restorations or mottled with decay. The earliest images are actualities: a train wreck, a parade with donkeys, children on bicycles trying to keep pace with a camera on the back of a streetcar. Then come primitively staged if prettily designed attempts at scenes from Shakespeare: Hamlet attacking Gertrude, Juliet stabbing herself over Romeo’s corpse. Rossellini reads from a contemporary poet who laments such voiceless bastardization.

Fanciful effects mark comedies, like a man being torn apart and reassembled via stop-motion, or the elaborately staged scenes from various productions of Dante’s Inferno, or the historical pyrotechnics of epics made by Giovanni Pastrone. A golden age is achieved with the stardom of melodramatic divas such as Lyda Borelli and Francesca Bertini. They radiantly clutch themselves and collapse.

A vivid star-filmmaker named Emilio Ghione is described in the commentary by critic Tim Lucas as looking like “Buster Keaton or Jack the Ripper.” He played criminal anti-heroes, while Bartolomeo Pagano became a star as strongman-hero Maciste in a series of films that used him as diversely as Godzilla. Derived from Hercules, Maciste was introduced as a Nubian slave in Pastrone’s Cabiria (1914), allegedly written by Gabriele D’Annunzio for literary pizzazz, but later films presented him whitely. It’s a curious historical factoid that cinema’s first recurring superhero started his fictional life as a black man.

Amid the fantasies, we glimpse fanciful works of science fiction indebted to Jules Verne or H.G. Wells. The 1919 Umanità, a downbeat post-WWI drama about two children as Earth’s survivors, was the only film directed by a woman named Elvira Giallanella. One feature available on YouTube is The Extraordinary Adventures of Saturnino Farandola (Le avventure straordinarissime di Saturnino Farandola), a 1913 effects epic by Marcel Perez. For alerting me to this alone, Italia – Fire and Ashes has my thanks.

All this is more information than you can glean simply by watching Italia – Fire and Ashes, since the filmmakers choose to identify neither the clips nor the quotations, leaving such data for the closing credits. Because Lucas chooses not to speak during Rossellini’s readings, instead discussing the writers and labeling most of the clips, this is a rare disc where the fact-hungry viewer might go directly to the commentary.

Still, watching Italia – Fire and Ashes “cold” gives a dream of poetic atmosphere untouched by mere facts. The cumulative effect of experiencing this dream is to be dazzled and intrigued by a window into the past, and to wish to see more of these films.

Italia – Fire and Ashes features three possible soundtracks: Rossellini did both the English and Italian versions, while a French reading was recorded with Fanny Ardent. Kino Lorber’s Blu-ray includes only the English option.

Focus on Louise Brooks (Flicker Alley)

Focus on Louise Brooks is a lovely package in a beautifully designed cardboard slipcase, pitched squarely at fans and fetishists of Louise Brooks. Anyone, however, may profit from a peek at its pleasures.

Brooks, who was briefly a silent star without quite becoming famous, had been forgotten until the 1950s, when critics and film buffs rediscovered a previously overlooked film, G.W. Pabst’s decadent Weimar production Pandora’s Box (Die Büchse der Pandora, 1929). Fortunately, Brooks was around to capitalize on her rediscovery via interviews and memoirs, and her reputation as a flapper with a modern appeal has remained with us ever since.

As one of the few certifiably iconic faces to outlast the silent era, Louise Brooks’ mystique has surrounded her lost or unavailable films. The good news is that as various titles get discovered or restored, we find that Brooks continues to justify her fanbase.

Flicker Alley’s Blu-ray is built around one of these restorations. Herbert Brenon’s The Street of Forgotten Men (1925) is an excellent melodrama among disreputable figures. Brooks appears briefly in an uncredited part near the end. Her eye-catching charisma is already clear, and we’re not surprised that bigger roles followed promptly.

This Blu-ray’s restoration premiered at the 2022 San Francisco Silent Film Festival, and PopMatters had the opportunity to review it then. As we wrote:

This richly arranged story begins in the Bowery, where the backroom of a bar is devoted to people who apply makeup and prosthetics, just like backstage in a theatre, before going into the streets to masquerade as phony cripples. The premise of Herbert Brenon’s The Street of Forgotten Men bears a passing resemblance to a Sherlock Holmes story, ‘The Man with the Twisted Lip’ (1891).

The most successful faker is Easy Money Charley (Percy Marmont), whose soft heart leads him to adopt an orphan in the off-handed manner of guardianship common to silent films. When the kid grows up to be played by Mary Brian and gets courted by a handsome young lawyer (Neil Hamilton), events lead to a certifiably amazing ending, not least because a highly recognizable Louise Brooks suddenly shows up in her debut role.

Restored this year by the Festival, this Paramount production is missing its second reel, which deteriorated decades ago. The best they could do was ‘reconstruct’ this reel via intertitles and still images. It’s too bad this reel is missing, but the rest of this splendid print makes an impact as only far-fetched silent melodramas can.

Quite a bit of icing is provided for this cinematic cake in the form of restored fragments of three otherwise lost films. Eight minutes of material exist for Frank Tuttle’s The American Venus (1926), set at the Miss America Beauty Pageant. Esther Ralston plays the lead, while Brooks plays a petulant contestant. Some of the pageant material was in early two-strip Technicolor, so the faded fragments here constitute Brooks’ only color footage.

About half an hour of footage survives from Alfred Santell’s Just Another Blonde (1926), featuring beautifully shot sequences at Coney Island’s Luna Park. Brooks plays the roommate to Dorothy Mackaill’s character, who’s being wooed by a handsome professional gambler played by Jack Mulhall. The romantic comedy boasted a climactic plane crash that sadly isn’t among the extant footage.

Perhaps most impressive among the fragments are the three sequences from Frank R. Strayer’s Now We’re in the Air (1927), a slapstick stunt epic starring Wallace Beery and Raymond Hatton doing a sort of Laurel & Hardy act. An aviation comedy set in WWI, it features the two saps in funny, hair-raising antics with biplanes, balloons, and bomb sites.

Louise Brooks appears as a French circus girl in a black tutu. In fact, Brooks played twins in a dual role, and we only get to see one of them briefly. Brooks-wise, we’re being deprived twice over. Now We’re in the Air was the most popular and widely seen of her films at the time, and now, it’s almost vanished.

Silent film musician Stephen Horne provides new scores for The Street of Forgotten Men and Now We’re in the Air. The other two fragments are scored by Wayne Barker.

All these silent films come with commentary. Pamela Hutchinson, a film historian who provides a background on Louise Brooks’ Hollywood career, speaks during The Street of Forgotten Men, while the fragments have comments by Brooks specialist Thomas Gladysz and film restorers. As with so many silent film revivals, the disc isn’t merely an appreciation but an act of love.