For even the most seasoned traveler, it was a nightmare of vile food, unsanitary conditions, endless waiting, and testiness from those supposedly in charge of the journey. Today, we would reflexively assume that this had to be a trip to the airport in the forlorn hope of reaching one’s destination within the next week or so.

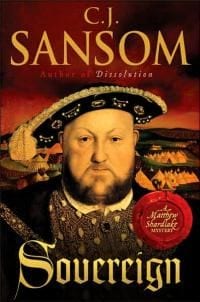

But in C.J. Sansom’s richly textured historical thriller Sovereign, which is set in the 1540s and in the darkening twilight of Henry VIII’s grip on power, the description refers to what was loftily called a Royal Progress.

Here the monarch ventured to the farthest reaches of his realm at the head of a vast retinue to awe his subjects with displays of pomp that were hardly justified by the circumstances. And while Henry VIII, the aging and paranoid monster at the heart of Sansom’s novel, made the progress with every creature comfort, his lesser courtiers and minor officials expected only the misery of trailing along in an endless cavalcade in his muddy wake with the rest of the vast horde of servants, camp followers and knaves that followed the king.

Sovereign is the third installment of a series Sansom began with Dissolution and continued with Dark Fire — two stark re-creations of Henry’s England that proclaimed the arrival of a first-rate historical novelist. If you are already tired of the sexed-up vision of the period in The Tudors, Sansom provides a sobering antidote.

Here is a world where life is short and brutal. Crows pick at the rotting corpses of felons left to dangle from gibbets as a warning to others. Religious persecution and political conspiracy are everywhere and trust in anyone is a dangerous assumption. The foul-smelling, festering ulcer on the leg of the now grossly obese king is, in Sansom’s melancholy vision, an emblem of the larger cancer eating into the body politic of England.

Sansom makes two bold decisions for this journey. At 582 pages (including a bibliography that attests to the range and diligence of his research), the book is almost long enough to see you through most of the wait for your luggage at the US Airways terminal. But in this case, the generous length is amply sustained as much by the consistently vivid evocation of the Tudor world as by the turns of the plot.

Sansom takes another risk in casting the story in the first person of Matthew Shardlake, the hunchback lawyer of Dissolution and Dark Fire. Historical fiction that takes this path often trips up by putting the narrator in the implausible and often clumsy position of explaining facts and background that may be new to the reader but are patently obvious to him.

With the exception of some arcane discourse on the dynastic credentials of various rival claimants to the throne seized by Henry’s father, Sansom is remarkably adept at avoiding the pitfalls of unfolding the story through one voice and perspective.

It helps that Shardlake, by his physical affliction and disposition, is an outsider casting the jaded eye of a disillusioned idealist on the venality and violence of the court. There is much further disenchantment as he goes about the business of serving as a sort of legal advance man for the monarch and vetting petitions to be presented to Henry.

Murder soon intrudes, and Shardlake’s mission is further complicated when he is given the responsibility of escorting a Catholic dissenter safely to the Tower of London, where he will be tortured unspeakably before execution. The problems test both the ingenuity and conscience of a decent man in a milieu where to turn one’s back is to invite the sudden stab of a knife.

Shardlake’s reward may be meager, but readers will find ample dividends in this trio of novels, which deserve the praise heaped on them in England.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)