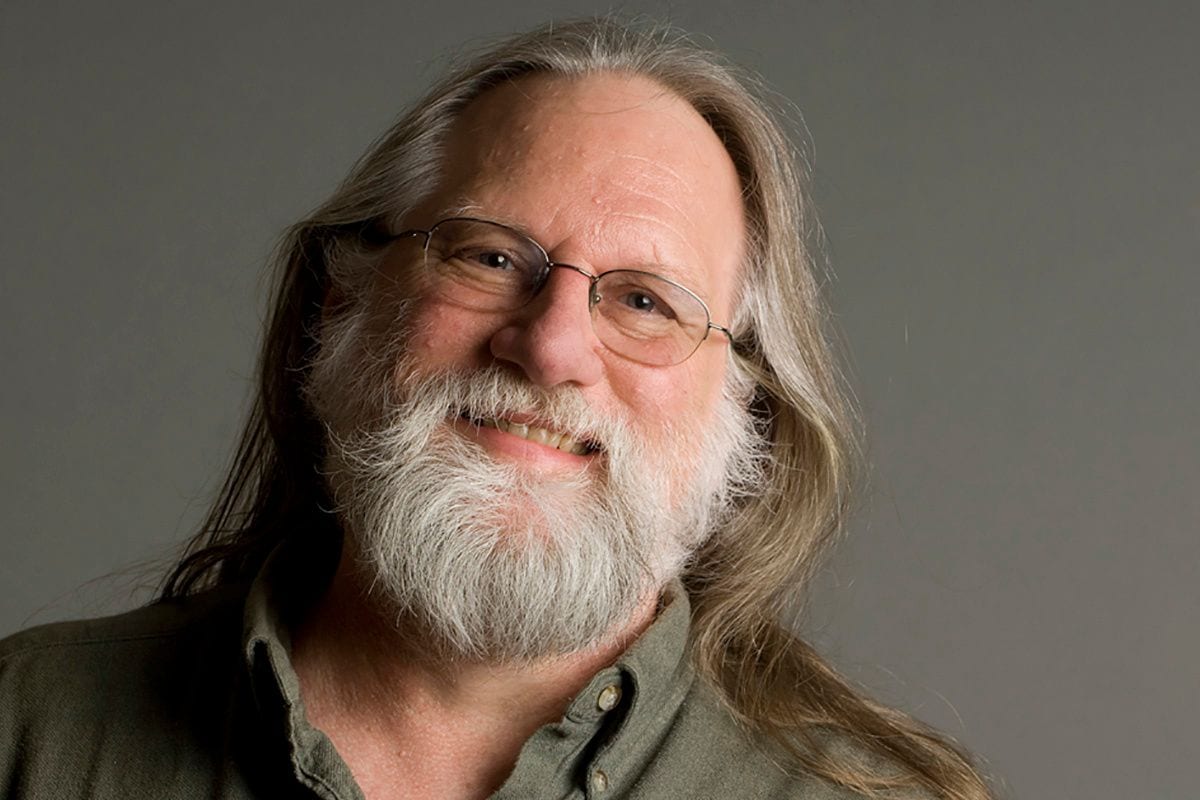

Todd Barton is a singular force in the world of music: An educator, whose tutorials on Buchla, Serge, and Hordijk synthesizers are respected around the globe, he also served for decades as Resident Composer at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival. Since retiring from that post circa 2012, he has had little time to slow down. Though Barton has a range of projects spotlighting new music in the works, he recently took time to reissue his 2003 set Ro, performed solo on the shakuhachi (a Japanese bamboo flute).

Ro is the lowest note of the instrument, with all the finger holes closed; blowing that note for ten minutes to an hour each day is considered traditional training as it focuses breathing, timbre and listening as well as embouchure.

Barton has collaborated with a variety of artists including Kronos Quartet and Ursula K. LeGuin. He spoke with PopMatters via Skype from his home in Ashland, Oregon.

* * *

Take me back to the start of this record. Where and when did it present itself to you?

It was back in 2003. I’d been playing shakuhachi, the Japanese bamboo flute, since about 1989. A friend of mine who builds shakuhachis, Monty Levenson, had built me a long, large one. It was two feet and seven or eight inches. I immediately fell in love with it. I connected with it. That’s unusual for shakuhachis. They’re not the easiest instrument to play. A day or two after having it, I went into my studio and turned the recording devices on and recorded that album. I improvised all the tracks, except for “Pulse” and “Improv”, which I multitracked.

Is that typical of how you work?

My day job then, actually my day and night job, my 24-7 job, was composing music for the Oregon Shakespeare Festival, incidental music for the plays. That’s highly collaborative art because it’s music to propel the story and written to a director’s specifications. Lighting designers and set designers can also offer input. It’s a highly structured environment for composing, so this was, at the time, definitely much more freeform. That was a nice balance and contrast. Since having retired from the Oregon Shakespeare Festival seven years ago, I found myself, especially with my electronic music, performing live. Completely improvisatorial. Many of the albums I’ve put out recently have been improvised. My Festival compositions were highly structured so my personal work, and outside of the Festival, free improv work during that time, Ro included, was a great and necessary contrast and balance.

It has to be liberating.

Yeah, because it’s so immediate. Yes, liberating! [laughs]

Do you think that the improvisational element to the recording also accounts for the meditative quality in the music itself?

Absolutely. I was exploring, and part of the meditative quality is that I’m following the sound, I’m listening to what the instrument wants to do and responding to its sounds and then saying, “Can it do this?” It’s an exploration as well as a meditation.

There’s that element of picking up a new instrument and feeling unencumbered by rules.

It speaks in a different way. It opens up different pathways of listening.

Do you remember the reaction to Ro when it came out?

I spoke with a theatre composer friend of mine who is now writing operas. He’s also retired. He was telling me in 2003, when he got the album, there was almost some sort of healing or integrating experience in listening to it, which he’s been doing for years.

What inspired the reissue of the album?

Clint Newsom at Flying Moonlight, the label, that brought it about. We had met, and he’d heard my Music and Poetry of the Kesh (2018) album. He asked if I had anything in my archive that I might like to re-release. I sent him a few things, and he immediately responded to Ro.

The album must have a special place for you as well.

Absolutely. It’s wonderful to come back to it. I actually enjoy listening to it! [Laughs.]

Can you listen to your albums comfortably or do you hear things you want to change?

I wouldn’t be putting it out there if I wasn’t happy with it.

How did you begin composing for theatre?

I was very lucky, growing up, to have great music teachers from the age of eight onwards in public schools. In fact, my third-grade teacher, when I was eight, taught a handful of us composition in a little private class twice a week. I was sold. I did music from third grade into high school. I went to music conservatory as a performance major on trumpet. By that point, I had picked up the recorder and was performing on a baroque trumpet and recorder and studying theory and counterpoint.

I also loved Shakespeare. I had a couple of incredible high school English teachers who totally turned me on to him. I was an avid Shakespeare reader as a teenager, and I loved music. A friend brought me up to the Oregon Shakespeare Festival after my Freshman or Sophomore year of college. I saw the festival. There was music in the plays. I went, “Oh man! It’s made for me!”

After my Junior year, I applied to be a musician at the festival. I got in, realized that the fellow that was composing was nearing retirement and loved having an assistant. A month before graduation, I wrote Angus Bowmer, the founder of the theatre and said, “I know you don’t have this position, but I’d love to apply for it. I’d be the Assistant Music Director.” They bought it! [Laughs.]

[laughs]

I became Assistant Music Director when I was 21. The next year, Bernie Windt, who was the Resident Composer/Music Director, retired. At that point, there was only one theatre, the outdoor theatre. By 1972 there was a large indoor theatre, and by the 1980s there was another, smaller indoor theatre. I sort of grew up as the festival grew.

The festival probably didn’t go year-round but I would imagine the preparation for it was.

I came in 1969. It was just a summer gig, for three months. And a month of prep. In the 1970s it started to become four or five months with a couple of months of prep. By the end of that decade and into the early 1980s, it became nine months out of the year. They run from mid-February to the end of October.

It got wonderfully nuts and crazy. Sometimes I’d be composing for three different plays at the same time. [Laughs.] Eventually, other composers would come in as part of a team for a specific director so instead of composing for eight or nine plays out of the year, I’d do something a little more manageable like five. [Laughs.]

So if you did Richard III in 1982 and then again in 2001, it’d be a new compositional process?

Absolutely. Mainly that’s because of the director’s vision. You can set Shakespeare just about anywhere you want. Midsummer Night’s Dream in 1979 was set in Alexander Dumas/Three Musketeer land. Six or seven years later it was set in a fictitious Mid-Eastern culture. I hired a Mid-Eastern ensemble to come in and record the music I wrote, which was way different than what I wrote the previous time. Down the road, it was done as something very minimalist, a Steve Reich/Philip Glass-type score. I’ve written five or six Midsummer Night’s Dream [scores], same for Romeo and Juliet, same for As You Like It. All the ones that get repeated every six or seven years.

Incredible.

Yeah. Once again: Lucky. What’s not to like about that job?

I’m trying to do the math on this: All the plays Shakespeare wrote and then to write music for each. Multiple times.

We’d do 10-11 plays. Four of those would be Shakespeare; then the others would be classics or from different cultures. At this point, I’ve written probably over 300 scores. And I’ve written for Shakespeare’s canon, which is probably 36 or so plays twice and some of those four or five times. If you break it down into music cues, which can be anything from 15 seconds to three-and-a-half minutes or more, I’ve written thousands of cues.

Do you have a score that you maybe felt indifferent to at first and then it turned out being better than you expected?

One that really sticks out is this: I had come back from a vacation to do the last play in the sequence, which usually goes in in August. After we opened in June I would take a couple of weeks off and the artistic director said, “The playwright and director don’t need music for this new adaptation of Dracula”.I said, “OK” and blithely went on vacation, came back, and they said, “No, no, no. We changed our minds!”

[laughs]

It was ten days before tech. I wrote an hour’s worth of music and was lucky enough at the time to be working with the Kronos Quartet. They came up, and we recorded for a day or two. I had written a score for two Kronos string quartets. Basically overdubbing themselves with completely different parts. Two quartets, two grand pianos, some electronics, waterphones. It was just one of those times where the muse, thank goodness, was around and I was able to create a ton of music, all of which I was happy with.

Where did the synthesizer show up?

I’ve always been fascinated by timbre. That’s what led me to go into early music, to play Renaissance, Medieval and Baroque music. I found the wind instruments especially fascinating for their timbal qualities. I used to go up to Portland every year to do a series of early music concerts. I became friends with a man named Douglas Levy. He had just put in electronic music studios in Venezuela, Berlin and, UCLA. He had a Buchla Music Easel. He said, “I bet you’d be interested in this.”

So, he also happened to release a landmark recording of Buchla 200 synthesizers. He was my entre into electronic music. I went up into the little space where I was staying at his place and didn’t come down for three days. I was so fascinated by all the different sounds I could discover. The shakuhachi has always for me been about tone color and discovering new timbres even within a single note.

The transition from acoustic instruments to electronic ones seems totally organic to me because I’m following the sound and following the tone color.

You do quite a bit of pedagogy. Was that something you always envisioned?

I guess I’ve always taught. When I first came to Ashland, when I was 19, as a musician, I would still teach trumpet and recorder. I would always teach, whether privately or at universities. Usually in very specialized subjects like Philosophy of Renaissance Music or Renaissance Music, Baroque Performance Techniques. Later on, I taught Computer and Electronic Music at the college level. And I taught courses in composition.

For the last seven years, I’ve been doing online tutorials for synthesizers. I just love sharing knowledge and information. One of the reasons I put things out there basically for free on YouTube and Vimeo is that I want to encourage people to explore and then share their knowledge. It’s more of a symbiotic relationship.

I assume you have four or five projects going at any time.

[laughs] Ah, yes I do. I just did an online album of music on my Serge synth. I have a brand new album coming out in July or early August, a solo analog synth album. A couple more in the fall. One is a live performance on the Buchla Music Easel that I did last October in London and a new release of unreleased Easel material. I also have a studio full of pet projects. I’m starting to toy with a video or book on everything I know about analog synthesis.

And somewhere in there, sleep?

[laughs] What’s that?

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)