They Started As One (Kind of) Band

Brace yourself if you do a web search for the Depraved. Search results weren’t an issue in the mid-1980s, when this hardcore punk band were rocking the town of Leamington Spa, Warwickshire, England. Now, even if you add “punk” to your terms, DuckDuckGo (not the information-eating maw of Google, please) will direct you to sites far removed from this nice, angry, noisy rock band. What an AI thingy (maybe a far more monstrous maw) will do with the Depraved is for you to find out, if you dare.

The Depraved released two short albums, 1985’s Come on Down and 1986’s Stupidity Maketh the Man, on the UK label Children of the Revolution Records. Raw and no doubt recorded for very few pence, these albums exhibit instrumental dexterity and imagination, especially in light of their genre.

On Come on Down, the band rock ferociously in English-punk style, but can downshift into surf rock and psychobilly interludes and, at one point, let a piano plink. The album consists not just of sides one and two but of the Mummy’s on “Valium Side and the Daddy’s on Blues Side”. Song titles such as “Fucked Up” and “KKK” suggest standard hardcore, but “Are We Getting Through?” and “Resident President” indicate minds at work. The record is so effective that the Depraved probably could have made a series of them—and ended up, like so many unversatile strugglers—boxed in and competing against their own best work.

Instead, Stupidity Maketh the Man displayed artistic growth. The title alone should’ve earned the Depraved more attention and might’ve if they’d recorded for a US label, such as the towering indie SST. Creativity and playfulness abounded, though. For example, the album has a Fireside and a Bedside. “Let’s Grow Some Flowers (Together)”, “Agent Orange”, “Purple September”, and a garage-rock cover of the Isley Brothers’ “Shout” indicate an awareness of the 1960s that straightforward punk rockers, especially English ones, seldom highlight.

Here, the English punk of Come on Down meets slower tempos, phase-shifted guitar, ringing guitar, a Beatles chord here, a Who rave-up there. More even than the British Invasion, though, the Depraved seemed under the influence of American hardcore bands, prominently SST’s Minutemen, Hüsker Dü, and Black Flag. They didn’t sound just like these bands, but they, too, were proudly displaying idiosyncratic impulses with a freewheelingnessworthy of the term postmodern.

They Became Another One

Then the Depraved did something unusual: adopting an even more positive attitude, expanding their sound to include even more overt 1960s influences, and changing their name to Visions of Change. From the Depraved to Visions of Change is the kind of amusing leap you don’t usually see outside of This Is Spinal Tap. Prince changing his name to an unpronounceable symbol, also known as the Prince glyph and the Love Symbol, comes to mind.

Prince’s vision of change didn’t happen until 1993, so we might say that Leamington’s finest beat the Purple One to the punch. Perhaps for a time, they were the Artists Formerly Known as the Depraved. Eventually, a very small portion of the world caught on to the changes.

In 1988, London’s Firefly Records released the self-titled debut album by the renamed band. Firefly was probably the band itself, disguised as a company, and Visions of Change turned out to be the company’s only release. Carrying on from the Depraved were singer Ian (last name Murphy); bassist Spencer (last name Hunt); and drummer Gigs (real name Paul McGivern). Guitarist and backup vocalist Lee Fester (real name Lee Murphy) became just Lee, but, more importantly, started playing Hammond organ and tambourine. Please point me in the direction of the other 1980s hardcore punk band with a full-time organist and tambourine player.

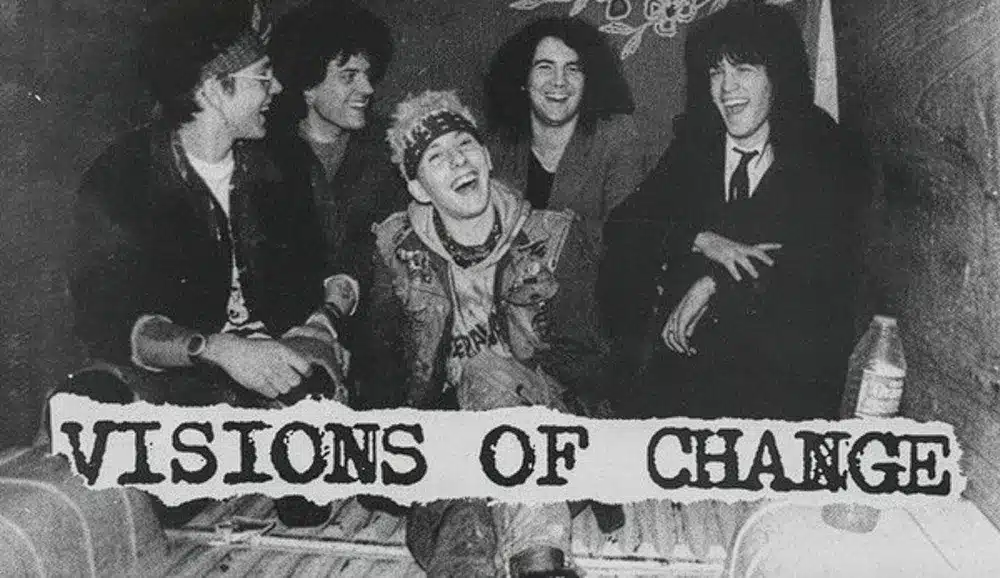

The group’s changes were reflected in the cover art. Gone were the Depraved albums’ artfully rough-hewn nods to punk iconography. The name Visions of Change became a full-type logo that would’ve fit somewhere between the Beatles’ Rubber Soul (1965) and the Stones’ Flowers(1967). On the front, the name sat in the middle of a rotating-paint-splatter effect; on the back, it appeared atop a blown-out photo collage. On the lyrics-and-notes insert, a band photo showed dudes who could have been from any time after the late 1960s, some sporting long hair and—a telltale sign—the drummer wearing a Black Flag T-shirt.

Now, what about the music? It’s interesting: not a little-known masterpiece, but more than a historical curiosity, good enough that it’s worth playing more than once, and each time wishing it were better, each listen revealing some aspect you hadn’t appreciated or been able to discern. Many punk bands and 1960s pop-rock bands had less to offer. Visions of Change were clearly writing and performing to their utmost, so the rest comes down to your taste.

If you like hardcore played in a sharp-edged thrash style, like Minor Threat, you probably won’t like this. If your taste runs to the melodic, such as the Minor Threat offshoot Dag Nasty, this might appeal. If you listen to early Hüsker Dü, Naked Raygun, and the Big Boys and don’t mind their dense, low-rent production—in fact, wouldn’t mind if the production was even denser and lower-rent—then you might appreciate this. Liking any of these bands definitely won’t guarantee liking another.

Few records benefit from a lyric sheet as much as Visions of Change does. The songs don’t sparkle with wit, but they have things to say, even if the things add up to “I keep trying” or “can’t take it anymore”. However, at least on my secondhand pressing of the original LP, the mix swallows the vocals so entirely, buries them in so much echo, that even reading the words doesn’t help discern them. What at first seems to be mere shouting turns out to be vocal interplay, with Ian delivering one line and Lee a follow-up. Without written versions of the words, understanding would be hopeless. Don’t listen for the words or hope to sing along. In short, a clearer mix would’ve helped the band do justice to itself.

The opener, “Roundabouts and Swings”, introduces the album’s concerns with time, memory, change, and struggle. Throughout these tracks, the singer wants to get along, to be true to himself without disrespecting others. “It’s just a question of what is right”, he sings in “Reciprocate”. “I’ve gotta learn how to relax, how to unwind”, he declares in “Be the Child”.

The music often begins as hardcore thrash, then shifts tempo. If enthusiasm alone made for a rewarding listen, “Under One Fist” would qualify, building up a head of steam. “Reciprocate” fearlessly includes a hard-rock portion with a guitar solo. “Burn Within” is 1960s riff rock, like the MC5 with organ. “Shades of Green” rocks full-throttle, slows for a long middle section, then speeds up again and offers lead-guitar shredding somewhere in the cacophony. “Anymore” is a more melodic grinder.

In a different universe, “Just Dreams” would have been the single, produced with gloss. The songwriting and execution suggest time spent listening to the Who, but the arrangement adds organ breaks. The song itself doesn’t match the best of the Depraved, but it beats Pete Townshend‘s lesser songs, the boring or verbose ones—or, for that matter, Paul Weller‘s most awkward Who-inspired excursions with the Jam.

The record’s three real surprises are “Muso”, a brief acoustic-guitar interlude like something Jimmy Page might have done for Led Zeppelin; “August a Go-Go”, a longer instrumental with guitar and organ interplay; and a cover of the Beatles’ “Day Tripper”.

My, how times have changed. The Clash declared, “No Elvis, Beatles, or the Rolling Stones / In 1977”, and here’s an English punk band, descended from the Clash, ripping through a Lennon-McCartney song. Lest you think Visions of Change recorded this one for attention, note that they give it the abandon of the Jimi Hendrix Experience’s anarchic BBC version, playing like their lives depend on putting their own stamp on a song they love, a spiritual predecessor. If this cover were playing in a record store, you might go up to the counter to ask who the artist was. You wouldn’t necessarily want to buy their music, but you’d be intrigued by it. You’d keep the name in a mental file and keep an ear out for more.

They Changed Again

By the time the lyric sheet had been written for Visions of Change, the band’s lineup had changed. The new members were listed below the ones who played on this album. Johnny (last name Barry) had replaced Spencer onbass. Kev (full name Kevin Webb) had joined as the second guitarist. A year later, by the time of the second and final Visions of Change album—1989’s My Minds Eye, released on the UK’s short-lived Big Kiss Records—the lineup had changed again. Andy (Forward) now played bass, and Ivor (Joseph) was the drummer, percussionist, and backup vocalist. Second guitarist Kev remained, along with Lee and Ian.

On My Minds Eye, the opener, “Endless”, sets the tone with prominent organ, full-fledged backing vocals, and the feel of garage-rock soul. Ian’s singing is prominent in the mix, which relieves the frustrating blur of Visions of Change but reveals his shortcomings. Still, he can sing, orat least give it a go and not just shout, and the band blasts carefully through its indie-rock and power-pop originals, which would’ve fit on college radio in 1989, in between, say, Soul Asylum’s “Runaway Train” and the Replacements’ “Left of the Dial”, though not as sparkling or memorable as either.

Sometimes, maybe most times, there’s a reason thatcertain musicians rise out of their indie grooves and others don’t. Repeated listening to My Minds Eye won’t necessarily be revelatory. The most compelling aspect of this record is that, four years after Come on Down, these musicians have brought so many elements besides punk into their sound that, if you didn’t know their history, you’d never suspect them of having been a British hardcore band called the Depraved.

They Left a Legacy (Sort Of)

Through change, consume change, as the Zen proverb puts it. Here’s to a bunch of DIY rockers who pursued their visions of change, pushing against their limitations. While we’re at it, here’s to the UK’s Boss Tuneage Records, which in 2012 released a two-CD set that gathered the complete works of the Depraved, the Visions of Changealbum, plus demos and John Peel tracks by Visions of Change. Good luck finding a copy of this collection, and I mean that both truly and ironically. The omission of My Minds Eye, whether by choice or because permission couldn’t be obtained, makes aesthetic sense, as that album really sounds like a different band.