Wes Craven’s contribution to horror cinema is often reduced to the creation of Freddy Krueger or the success of Scream (1996), but that framing obscures the continuity of his work. Across decades, Craven developed a consistent authorial voice rooted in verbal domination, performative cruelty, and psychological control.

That voice appears first in grindhouse form, becomes fully articulated through Freddy Krueger, fragments through imitation and commercialization, and is ultimately reclaimed through conscious self-interrogation. The evolution of Craven’s villains maps directly onto the evolution of Craven himself as a filmmaker.

Wes Craven’s early professional work before horror, including technical roles in adult filmmaking, shaped his understanding of representational limits. Entering horror after exposure to material beyond its conventional thresholds meant Craven approached fear through implication and restraint. He repeatedly demonstrates an awareness of what does not need to be shown to be felt. Language, timing, and psychological pressure become his primary tools. Violence arrives only after authority has already been established.

Artfully Dreadful Craven

Freddy Krueger’s Verbal and Physical Authority Before Myth

Wes Craven’s first clear articulation of his horror voice appears in The Last House on the Left (1972) through Krug Stillo, the leader of a sadistic gang. The film, a reinterpretation of Ingmar Bergman’s The Virgin Spring (1960), centers on Mari Collingwood, a virginal teenager whose innocence amplifies the terror of her abduction, rape, and murder. Mari’s vulnerability establishes the stakes of Wes Craven’s early exploration of domination and authority.

Krug exerts power through both verbal commands and physical violation. When he orders Mari to “Piss your pants,” the line is an immediate assertion of ownership, stripping autonomy and dignity before any bodily harm occurs. This verbal cruelty foreshadows Freddy Krueger’s linguistic domination: the terror begins in language. However, in Last House on the Left, Craven also foregrounds the physical counterpart — Krug forces the “role” of boyfriend through rape before inflicting finalized violence.

The sexualized violence functions narratively as both trauma and moral trigger: Mari’s parents enact revenge, and the audience witnesses the consequences of cruelty. Early in his career, Craven combined implication and moral gravity, showing that terror is most effective when it connects to both social roles and bodily vulnerability. These dynamics — innocence under threat, relational domination, and authority established prior to violence — will later evolve into Freddy’s dream-world omnipotence and Ghostface’s conversational mastery.

Even the marketing of The Last House on the Left reveals Craven’s early awareness of audience psychology. The film’s famous tagline—“It’s only a movie”—functions as a defensive mantra rather than reassurance. By explicitly reminding viewers that what they are about to see is fictional, the poster paradoxically admits that the material threatens to exceed normal cinematic boundaries.

This is an early form of Craven’s meta-horror impulse: the acknowledgment that fear does not remain confined to the screen, and that spectators are participants, not passive observers. Long before the creation of New Nightmare (1994) and Scream, Wes Craven was already negotiating the space between fiction, responsibility, and audience complicity.

Sexualized Threats and the Evolution of the “Virgin” Motif

Building on Krug’s verbal and physical domination, a recurring theme in Wes Craven’s work is the interplay of innocence, sexualized threat, and relational control. In The Last House on the Left, Mari’s virginity amplifies the horror of Krug’s assault, where verbal commands and physical violation are intertwined. By the time of A Nightmare on Elm Street‘s release in 1984, sexualized undertones remain but are largely symbolic: Freddy’s glove emerging from the bathtub between Nancy’s legs and the tongue in the phone call suggest sexualized menace without actual consummation, reinforcing power and violation through implication rather than act.

In Scream, the virginity motif resurfaces through Billy’s desire for Sidney, with sexual intent linked to the threat of death. Unlike Last House on the Left, Sidney’s agency and survival transform the trope: sexual threat is present, but paired with self-aware horror literacy and the possibility of resistance. Across these films, Craven explores sexualized power as a component of domination, refining its use from literalized trauma to psychologically and symbolically charged terror.

Mars and the Introduction of Horrifying Pleasure

In The Hills Have Eyes (1977), Wes Craven advances the blunt voices in Last House on the Left by introducing spectacle and enjoyment to grim proclamations. Mars retains Krug’s sadism and sexual menace but adds theatrical intent. His taunt — “Baby’s fat. You’re fat. Fat n’ juicy.” — fuses hunger, mockery, and anticipation into a single act of domination. Speech becomes appetite.

Deformity externalizes the moral corruption, but the true violence remains verbal. The desert environment amplifies this effect, creating long pauses where language hangs in the air. Craven moves from cruelty as control to cruelty as pleasure, refining his understanding of terror as something staged and savored.

“I’ll see the wind blow your dried-up seeds away. I’ll eat the heart of your stinkin’ memory. I’ll eat the brains of your kid’s kids! I’m in, you’re out!” – Papa Jupiter.

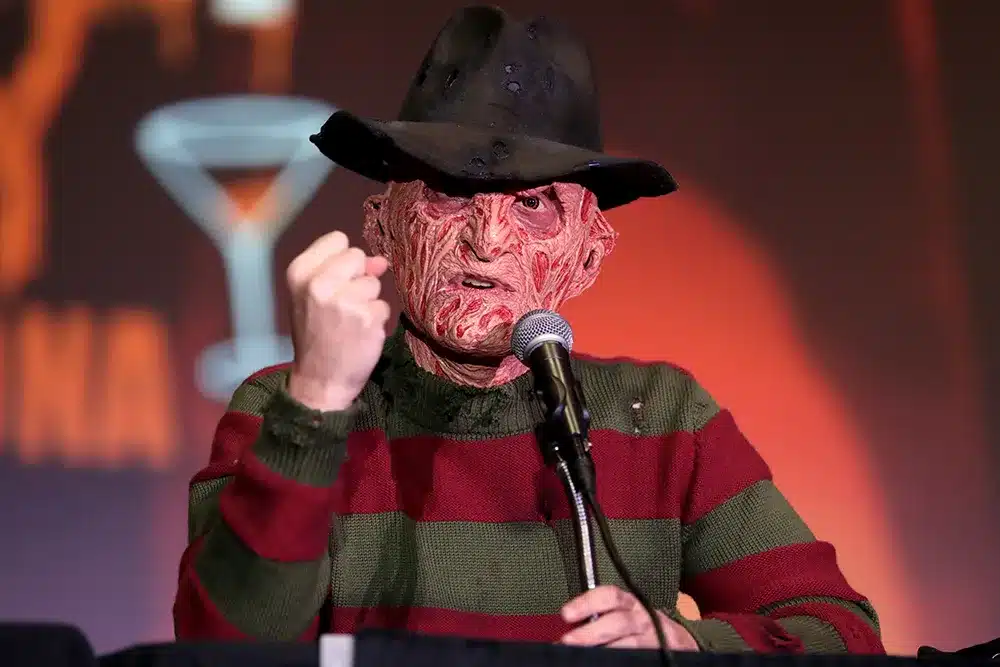

Freddy Krueger’s Total Linguistic Dominion

Freddy Krueger represents the full articulation of Wes Craven’s horror voice. All prior elements converge: verbal domination, bodily distortion, performative pleasure, and metaphysical authority. Dreams remove physical constraints and allow language to operate as law.

In Tina’s death scene, Freddy explicitly replaces divine authority:

Tina: “Please God…”

Freddy: “This… is God.”

The line precedes Tina’s murder and the infamous ceiling sequence, where gravity and architecture obey Freddy’s will. Authority is established before violence occurs.

Freddy repeatedly occupies relational roles to assert dominance. When he tells Nancy, “I’m your boyfriend now,” and then flicks his tongue through the receiver, the threat is invasive. To justify his claim, Freddy ultimately eliminates Glen. Glen is not confronted or challenged but absorbed by the dream itself, swallowed by the bed. The boyfriend role is structurally removed.

His act of cutting his own fingers off in front of Tina demonstrates the futility of resistance. Pain does not weaken him. Attempting to harm Freddy only reinforces his control. Freddy frequently adopts institutional language. “No running in the halls” reframes survival as misbehavior. He speaks as “God”, “lover”, “teacher”, and “disciplinarian”. Identity is fluid because authority is absolute.

Wes Craven’s Side Stories: Experimenting Beyond Freddy

Even after the fully realized voice of Freddy Krueger, Wes Craven continued to explore the same authorial patterns in new characters. Shocker (1989) and Vampire in Brooklyn (1995) demonstrate that the voice—verbal dominance, psychological control, and performative cruelty—remained alive within him, but could be expressed through characters other than Freddy.

In Shocker, Horace Pinker adapts Craven’s methods to a technological environment. He communicates menace through television and media, taunting and manipulating victims verbally while asserting omnipresence. The terror derives not just from his physical acts but from the sense that Pinker is everywhere at once, echoing Freddy’s dream omnipotence. The verbal interaction—the insults, mockery, commanding presence—carries the same pleasure in control that defined Freddy, but the medium shifts the impact from intimate dream invasion to technological omnipresence.

Vampire in Brooklyn approaches the voice differently. Eddie Murphy’s vampiric character presents charm and humor as instruments of control, blending seduction and menace. Dialogue becomes the knived finger; his wit, timing, and relational manipulation echo Freddy’s fluid roles as God, teacher, or boyfriend. Craven is exploring verbal authority and psychological domination in new forms, showing that Freddy was not the only vehicle for his voice of violence.

Cultural Echoes: Pennywise, Candyman, Chucky, Leprechaun, the Trickster, and the Djinn

Stephen King’s It (1986) introduces Pennywise, a predator whose performance and cunning echo Freddy’s linguistic dominance. Pennywise studies victims, adapts his presentation, and toys with them psychologically before striking. Unlike Freddy, he does not rely on humor or vulgarity; his “playfulness” is filtered through false innocence, creating a deceptive, intimate terror. Fear becomes interactive rather than purely physical.

Candyman inherits elements of the Freddy voice, particularly cunning and liminality. He exploits belief and legend, appearing only when invoked, with pain and language deployed deliberately to assert control. He performs terror ritualistically, reflecting Freddy’s understanding of the performative dimension of horror.

When Tom Holland’s Chucky (Child’s Play, 1988) inherits Freddy’s profanity and aggression, from “Hi, I’m Chucky. Wanna play?” onward, intimidation is constant. The pleasure in taunting remains, but authority dissipates through excess. Similarly, the Leprechaun exaggerates jokesterism into pure camp. Rhymes frame kills as punchlines.

Brainscan (1994) mimics late-era Freddy’s performative excess. The Trickster is flamboyant, deformed, taunting, and theatrical — dancing, joking. He demonstrates invulnerability by cracking his fingers one by one while joking about it, a clear echo of Freddy cutting his own fingers off in front of Tina. But where Freddy’s act establishes absolute authority — proof that resistance is meaningless — the Trickster’s version is imitation without consequence. He urges the protagonist to play, yet never gets his hands dirty.

The Djinn in Robert Kurtzman’s Wishmaster (1997) translates Freddy’s rule-bending into the semantic realm. Twisting wishes through precise technicality and delivering taunting commentary, he operates as a conversational manipulator, showing how Freddy’s principles—language as threat, pleasure in anticipation—can survive in alternate settings.

This wave of imitations confirms Craven’s influence: the voice of Freddy resonates, even when he himself is not present.

Commercialization and the Hollowing of Freddy Krueger

This dilution reaches its apex within Freddy’s own franchise. As sequels progress, humor arrives earlier and more frequently. One-liners replace anticipation. Freddy shifts from invasive force to familiar entertainer.

Commercialization transforms Freddy into a mascot. Repetition neutralizes threat. Without Wes Craven’s discipline, the balance between implication and exposure collapses. Terror becomes spectacle, and the voice loses authority.

Reclaiming the Horrific Voice

New Nightmare is Wes Craven’s explicit response to the dilution of Freddy Krueger through commercialization. Unlike the Elm Street sequels, the film frames Freddy as a mythic, almost autonomous entity weakened by repetition, whose presence has crossed into the real world. Craven himself appears, playing a version of the director, haunted by his own nightmares and attempting to write a script that can contain or resolve them. The act of writing becomes a metaphor for authorship: he exerts control through creation, yet the material—the Freddy demon—asserts its own influence.

Heather Langenkamp’s role is central; her participation is necessary for the script to conclude. The interplay between the written narrative and the “real” intrusion of Freddy demonstrates Craven’s negotiation with his own horror voice: he is both master and subject, guiding terror while being influenced by it.

Freddy’s verbal tactics remain central. He resumes phone calls, a crucial evolution of his linguistic dominance. When he threatens Heather by speaking about her son — “I touched him” — the line echoes Freddy’s earlier occupation of relational roles. He no longer needs to appear physically. The terror lies in implication, in the suggestion of access, in the certainty that boundaries have already been crossed. As with “This… is God” or “I’m your boyfriend now,” the declaration precedes proof. Language establishes reality.

Heather must consciously step into the role Freddy once unconsciously exploited, transforming New Nightmare into a negotiation among creator, creation, and victim. Craven reasserts control not by silencing the voice, but by understanding it, framing it, and limiting its use. Speech becomes rare again and, therefore, powerful.

In this way, New Nightmare functions as the essential bridge to Scream. It marks the moment where Craven regains authorship over his horror voice while simultaneously exposing its mechanics. What follows is not a return to Freddy, but more of a confident farewell to that medium and a translation of that authority into a new, fully postmodern form.

Ghostface’s Postmodern Authority

Scream‘s Ghostface represents the culmination of Wes Craven’s horror voice, relocated almost entirely into conversation. Where Freddy ruled dreams, Ghostface rules dialogue. From the opening scene, language is the weapon, the setting, and the method of control.

The most famous line in the film — “What’s your favorite scary movie?” — is a test. It immediately establishes hierarchy: Ghostface knows the genre, controls the conversation, and forces the victim into participation. This mirrors Freddy’s dominance in dreams, where victims must engage on his terms or die.

The killer explicitly references Freddy early in the call:

Casey: “Um… Nightmare on Elm Street.”

Man: “Is that the one with the guy that has knives for fingers?”

Casey: “Yeah, Freddy Krueger.”

Man: “Freddy, that’s right. I like that movie. It was scary.”

Immediately after, Ghostface introduces relational destabilization:

Man: “So, do you have a boyfriend?”

This sequence deliberately aligns Freddy and Ghostface. Freddy replaces God and boyfriend; Ghostface follows the same progression. Conversation shifts from trivia to intimacy to threat. The escalation is linguistic, not physical.

When Ghostface finally states, “I’m going to gut you like a fish,” the line functions exactly like Freddy’s declarations. An assertion of inevitability, the threat matters because the authority has already been established. As with Freddy, the victim is linguistically trapped before being physically pursued.

Knowledge of horror films becomes a survival skill. Just as Nancy learns the rules of dreams, Casey is forced to navigate genre conventions in real time. Horror literacy offers a fighting chance. Ignorance is fatal. The horror film itself becomes the dream world: a structured space with rules that can be manipulated — but only if recognized.

Ghostface kills the boyfriend first, echoing Freddy’s destruction of Glen before fully targeting Nancy. Relational protection is removed. Only after this symbolic act does Ghostface pursue Casey directly and fulfill his promise. The pursuit mirrors Tina’s death scene in Nightmare on Elm Street: isolation, psychological pressure, and spatial manipulation precede physical violence, with both blonde characters being red-spattered demonstrations of the power these killers harness.

Craven’s cameo as the janitor wearing a Freddy sweater reinforces this lineage. Visually, it recalls Freddy’s “No running in the halls” scene — institutional authority enforced through language. Meta-textually, it signals authorship. Craven places himself inside the film as the voice behind both Freddy and Ghostface. He is not merely referencing his past work; he is acknowledging that the same voice operates here, now refined and fully self-aware.

Ghostface is Freddy without mythology. No dream logic, no supernatural rules — only language, timing, and control. Conversation itself becomes the killing ground.

After Wes Craven: Mood as Legacy

Following Scream, late-1990s horror absorbs Wes Craven’s influence at the level of tone rather than character. Films such as Jamie Blanks’ Urban Legend (1998), Jim Gillespie’s I Know What You Did Last Summer (1997), and Steve Miner’s Halloween H20: 20 Years Later (1998) adopt self-awareness, sharp dialogue, and structured pacing, but the killers lack linguistic authority. Intelligence permeates the film’s structure rather than the villain’s presence.

The progression from Krug to Freddy to Ghostface traces the development of a singular horror voice. Craven begins with verbal cruelty, refines it into performative domination, watches it fragment through imitation and commercialization, and ultimately reclaims control through self-awareness and restraint. Wes Craven did not merely create monsters; he taught horror how to speak — and when to stay silent.

- Craven, Freddy, and That Dream in Your Head

- Wes Craven – Horror’s Most Influential Heavyweight?

- ‘Deadly Blessing’ Is Wes Craven’s Misstep on the Way to Elm Street

- Select ‘The People Under the Stairs’ Is Craven’s Most Original, Deranged, and Off the Wall Film ‘The People Under the Stairs’ Is Craven’s Most Original, Deranged, and Off the Wall Film